12 Times the Palme d’Or Was Awarded to the Wrong Movie

Soderbergh over Spike? ‘The Son’s Room’ instead of ‘Mulholland Drive’? No love for Truffaut or Varda? By and large, the world’s most prestigious prize in cinema lands in the right hands — but not always.

,

“”

Do The Right Thing, Paul Benjamin (center), Robin Harris (2nd from right), Frankie Faison (right), 1989 Universal/Courtesy Everett Collection

Jury deliberation at the Cannes Film Festival is a famously secretive process. Each May, the world’s most prestigious film event assembles a panel of roughly eight distinguished figures — directors, actors, craftspeople, and occasionally even a critic or two — to decide which film will take home the Palme d’Or. The assignment is as grueling as it is impossibly glamorous: Over 12 intense days, the jury will watch, discuss and assess roughly two dozen auteur-driven films. By night, they walk red carpets, attend glitzy galas, and are spotted at dinners and parties up and down the Croisette — all while maintaining a strict vow of silence about their impressions of the movies on the festival’s screens.

What goes on behind the closed doors of the suite at the historic Hôtel Martinez, where final deliberations take place, is rarely disclosed. Yet rumors do emerge. (Did James Gray really threaten to quit the 2009 jury because of Isabelle Huppert‘s “dictatorial behavior”? Is it true that Ethan Coen found Xavier Dolan painfully insufferable at the 2015 festival? It’s hard to know for sure, but the stories remain irresistible Cannes lore.) What’s certain is that locking a group of highly distinctive artists in a room and forcing them to compromise over an aesthetic judgment of global consequence can lead to some surprising outcomes.

In some years, aesthetically radical entries seem to cancel each other out and the jury ends up converging on a more conventional middle ground (see below for the astounding case of Nanni Moretti’s The Son’s Room triumphing over Mulholland Drive and The Piano Teacher). Other times, a jury that’s expected to tilt conservatively surprises with a choice that’s daring yet artistically defensible (as when Steven Spielberg’s jury crowned Abdellatif Kechiche’s three-hour erotic drama Blue Is the Warmest Colour over the Coen Brothers’ Inside Llewyn Davis). And then there are years when the competition is simply too stacked for any single film to claim the top prize without endless debate (In the year 2000: Dancer in the Dark over In the Mood for Love and Yi Yi? Cannes heartbreak at its finest.)

But there are also surprisingly numerous occasions when the jury — by committee, by compromise, or by sheer blind spot — just gets it wrong.

With the clarity that only hindsight allows, here are a dozen times the Cannes jury talked its way into folly — along with the films we believe should have claimed the Palme d’Or instead.

-

“”

1956: Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle’s ‘The Silent World’ Over Satyajit Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali’

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection Here was the year trifling novelty triumphed over historic humanist vision. That’s not to say Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Louis Malle’s documentary is without charm. The film’s vivid underwater cinematography was an otherworldly, Avatar-like revelation in its day, helping Cousteau and Malle become the first doc directors in Cannes history to take home the top prize. Today, their colorful crowd-pleaser is mostly only remembered as an inspiration for Wes Anderson’s The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. Ray’s Pather Panchali, meanwhile, is widely hailed as a landmark — the movie that introduced the world to one of cinema’s great humanists. Conspicuously, Cannes’ 1956 jury was majority-French (seven out of 12 members, including jury chair Maurice Lehmann), suggesting some local bias was at play. The jury was nonetheless aware it had seen something significant in Ray’s masterwork. For the first and only time in Cannes history, the festival created a “Best Human Document” prize to honor Pather Panchali. The token honor undoubtedly helped put Indian neorealism on the map, but many of the sentiments that contributed to Silent World‘s elevation over Ray’s masterpiece have aged horrendously. (“I don’t want to see a film of peasants eating with their hands,” François Truffaut was alleged to have said at the time.)

“”

-

“”

1957: William Wyler’s Friendly Persuasion Over Ingmar Bergman’s ‘The Seventh Seal’

Image Credit: Courtesy of Cannes This is not to knock Friendly Persuasion. William Wyler’s Western, starring Gary Cooper as a Quaker whose finds his pacifist beliefs challenged with the onset of the American Civil War, is an amicable, perfectly watchable, slice of Golden Age Hollywood entertainment. But the competition line up for the 10th Cannes festival featured at least three genuine cinematic classics: Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, Federico Fellini’s Nights Of Cabiria and Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped and a pair of superb European dramas in Jules Dassin’s He Who Must Die, and Andrzej Wajda’s Kanal. Even if the jury, under French writer André Maurois, wanted a Hollywood movie, they had a much better one available in the form of Fred Astaire-Audrey Hepburn vehicle Funny Face. Perhaps Maurois was using the prize as a way to honor Michael Wilson, the blacklisted screenwriter who had his name stripped off Friendly Persuasion after he refused to name names. Honorable, perhaps, but still a lousy choice. The Seventh Seal is an indelible part of the world cinema cannon. Friendly Persuasion is an answer in a pub quiz.

“”

-

“”

1959: Marcel Camus’ ‘Black Orpheus’ Over François Truffaut’s ‘The 400 Blows’

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection At the time, Marcel Camus’ retelling of the classic tragedy of Orpheus and Eurydice, staged as a musical during Carnaval in 1950s Rio de Janeiro, featuring an all-Afro-Brazilian cast, probably felt revolutionary. How else to explain why this forgotten footnote of a film snatched the Palme away from a pair of now-iconic French classics: Francois Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour? The Cannes jury wasn’t the only one swept up. Black Orpheus went on to win the Oscar for best foreign film. But sharp-eyed critic Jean-Luc Godard got it right in his Cannes review. “What offends me about this adventurer’s film is that it contains no adventure, or this poet’s film, that it contains no poetry.” Even in 1959, Camus’ depiction of Rio’s lush beaches and sensual, colorful favelas feels like exotic Euro-tourism and postcard romance.

“”

-

“”

1962: Anselmo Duarte’s ‘Keeper of Promises’ Instead of Agnès Varda’s ‘Cléo from 5 to 7’

Image Credit: Photofest Keeper of Promises (O Pagador de Promessas), an at-times poignant drama about faith and social injustice, is the only Brazilian film ever to win the Palme d’Or. It’s also a painfully mediocre movie that’s very little seen today. It pales against at least two of the other contenders at Cannes in 1962, both of which are now stone-cold classics of European art cinema: Agnes Varda’s New Wave delight Cléo from 5 to 7 and Michelangelo Antonioni’s modernist meditation on alienation, L’Eclisse. And there was more: Pietro Germi’s Divorce, Italian Style, Robert Bresson’s The Trial of Joan of Arc and Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel. What a year! Reportedly, the jury’s decision was surprising in 1962 — it has grown outrageous with time.

“”

-

“”

1986: Roland Joffé’s ‘The Mission’ Over Andre Tarkovsky’s ‘The Sacrifice’

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection The Mission is a reasonably sturdy (if turgid) period epic, starring Robert De Niro and Jeremy Irons near the peak of their powers. It also features lush cinematography from Chris Menges and a soaring Ennio Morricone score. But is it the final masterpiece of one of cinema history’s ultimate auteurs? No, it certainly is not. A jury led by studio mainstay Sydney Pollack (fresh off Oscars success with Out of Africa) shocked the festival by handing the Palme to “just the sort of lumbering white elephant” one would expect from the Oscars rather than Cannes, as Time critic Richard Corliss put it. Andre Tarkovsky’s swan song, meanwhile, a work of haunting imagery and profound spiritual depth, was the clear emotional favorite at the festival, no less so since the exiled Soviet master was lying dying of cancer in a Paris hospital at the time. Giving voice to the outrage of cinephiles all along the Croisette, French producer Daniel Toscan du Plantier reportedly stormed up to juror Philip French in the lobby of the Palais after the Palme ceremony to exclaim, “You are a member of the jury, non? You have disgraced yourselves. This will be remembered as a night of shame.”

“”

-

“”

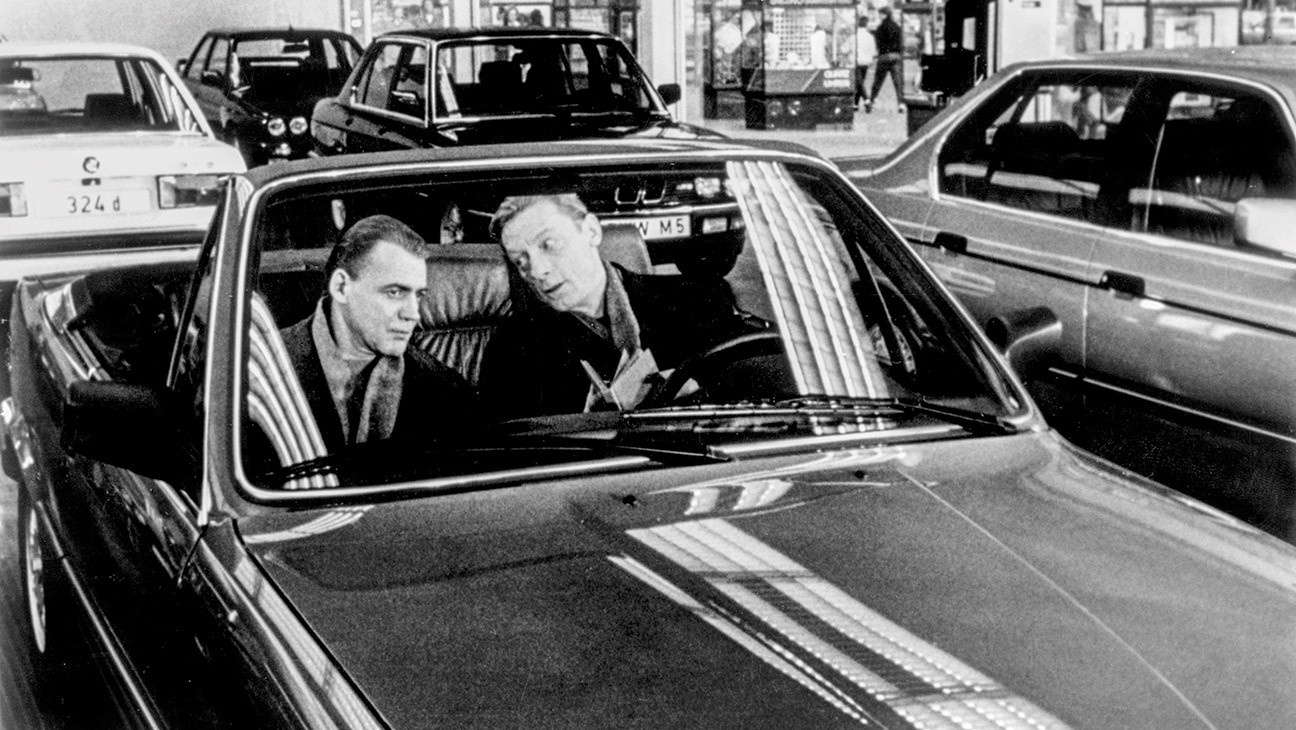

1987: Maurice Pialat’s ‘Under the Sun of Satan’ Over Wim Wenders’ ‘Wings of Desire’

Image Credit: Courtesy Everett Collection The 1987 awards ceremony is the stuff of Cannes legend, emblematic of the festival’s high drama and combative critical spirit. The Palme that year — on the festival’s 40th anniversary — went to French filmmaker Maurice Pialat’s Under the Sun of Satan, an austere religious drama about a tormented country priest — starring Gérard Depardieu, France’s biggest star at the time. Pialat is rightly considered a major figure and the film has its admirers, then and now, but the competition’s clear frontrunner was Wim Wenders’ lyrical fantasy Wings of Desire, now an icon of world indie cinema. Pialat had long been an enfant terrible of the French film world (forever clashing with critics), and some speculated the jury — nearly half of which was French — felt he was overdue for major recognition, lending a semi-“lifetime achievement” aura to his surprise win. The reaction to Under the Sun of Satan’s victory was nonetheless historically hostile. During the ceremony inside the Palais, the audience erupted in boos and whistles of disapproval as French actor Yves Montand announced Pialat’s film as the Palme d’Or winner. Taking the stage, Pialat raised his fist and shouted back at the crowd: “I am happy tonight for all the whistles and shouts directed at me — and if you don’t like me, I don’t like you either!” Bonus points for punk rock spirit, then — but Wings of Desire has proved the far more enduring film in both influence and affection.

“”

-

“”

1989: Steven Soderbergh’s ‘Sex, Lies, and Videotape’ Over Spike Lee’s ‘Do the Right Thing’

Image Credit: Photofest Another key chapter of Cannes lore. Sex, Lies, and Videotape, the low-budget debut of a 26-year-old Steven Soderbergh was a sensation at the 1989 festival — a distinctive new voice that signaled the start of the 1990s American independent film wave. There was just one problem: Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing premiered that same year. Roger Ebert would later write: “I have been given only a few filmgoing experiences in my life to equal the first time I saw Do the Right Thing. Most movies remain up there on the screen. Only a few penetrate your soul. In May of 1989, I walked out of the screening at the Cannes Film Festival with tears in my eyes.” And yet, Soderbergh went home with the Palme and Lee left completely empty-handed (Ebert’s wife, Chaz, later stated that her husband had been so appalled by the festival’s complete snubbing of Lee that he privately discussed boycotting future editions of Cannes). Lee wasn’t discrete about the fact that he felt robbed. Speaking of the Cannes jury chief that year, he told reporters: “Wim Wenders had better watch out ’cause I’m waiting for his ass. Somewhere deep in my closet, I have a Louisville Slugger with Wenders’ name on it.” Eventually, the two auteurs would come to joke about the incident. Sex, Lies, and Videotape remains well regarded. Lee’s examination of racial tension in Brooklyn on the hottest day of the year? It’s a full-fledged cultural watershed.

“”

-

“”

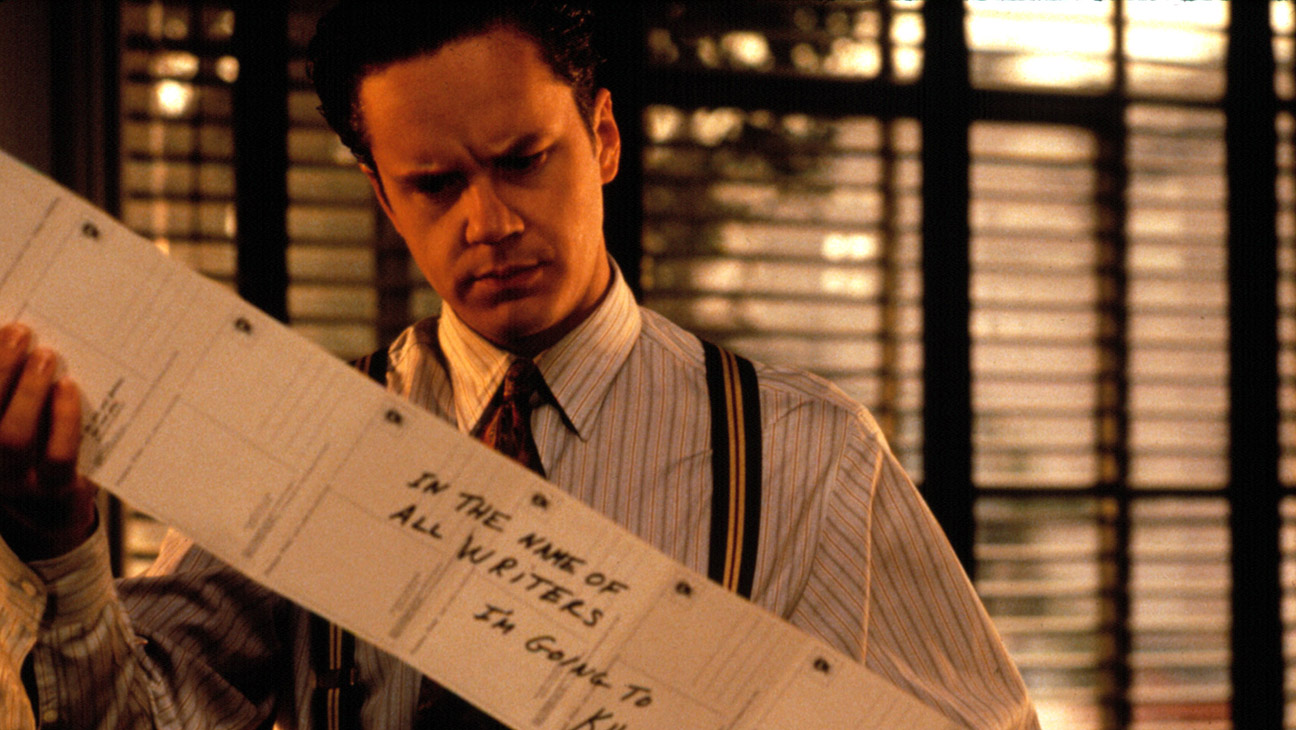

1992: Bille August’s ‘The Best Intentions’ Over Robert Altman’s ‘The Player’

Image Credit: Miramax/Courtesy Everett Collection The 90s featured several incidents of temporary insanity, from the embrace of parachute pants and scrunchies to giving the 1992 Palme d’Or to Bille August’s The Best Intentions. While the former are back in fashion, the latter may never make sense. The Danish director, already a Palme winner for his serviceable 1988 period piece Pelle The Conqueror, here serves up a reheated dish of Ingmar Bergman fan fiction, working from a Bergman-penned script but delivering a tedious Scandi melodrama about priests and frustrated housewives living a life quite ordinary in rural Uppsala. By picking August over Robert Altman’s The Player, the jury, perhaps unsurprisingly, given it was led by Gérard Depardieu, showed it would rather award a bad copy of the kind of film people used to like than the single best satire of Tinseltown ever made.

“”

-

“”

2001: Nanni Moretti’s ‘The Son’s Room’ Over David Lynch’s ‘Mulholland Drive’

Image Credit: Universal Focus/Photofest Here we have a howler for the ages. Moretti’s film is arguably fine. An emotionally effective drama about a family coping with the sudden death of a son, it’s certainly better than the Italian director’s soggy, recent Cannes offerings. But it’s an embarrassment to even ask: Is The Son’s Room better cinema than David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive or Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher, both in competition that year? In remarks at the awards ceremony, jury chief Liv Ullmann hinted at a fraught selection process, saying Moretti’s movie “touched our hearts” but that the jury’s deliberations involved much “passion and even anger.” The only reasonable explanation is that The Son’s Room emerged as the safe middle-ground choice between impassioned champions of the two aesthetically radical masterpieces.

“”

-

“”

2003: Gus Van Sant’s ‘Elephant’ Over Lars von Trier’s ‘Dogville’

Image Credit: Lionsgate/Courtesy Everett Collection Taking pot shots at American culture is a good strategy if you want to win in Cannes but it was a genuine shocker when the jury handed the Palme to Gus Van Sant’s slacker school shooter drama. The film had its fans, but most critics eviscerated the low-budget effort, originally made for HBO, and loosely inspired by the Columbine school massacre, for its refusal to provide any insight into such random acts of violence. If the jury really wanted to show its anti-American credentials, it have a much better deconstruction of the narrative lies at the heart of the U. S. of A. in Lars von Trier’s Dogville. “Von Trier has judged America, found it wanting and therefore deserving of immediate annihilation,” read one (disapproving) review at the time. Can anyone watching the news today argue that Lars doesn’t, perhaps, have a point?

“”

-

“”

2004: Michael Moore’s ‘Fahrenheit 9/11’ Over Park Chan-wook’s ‘Oldboy’

Image Credit: Tartan Releasing/Courtesy Everett Collection At least two lessons can be drawn from this edition’s baffling outcome: Nodding to political exigencies of the moment seldom yields sound aesthetic judgment, and so began Cannes’ long, continued snubbing of Korean auteur Park Chan-wook. The year was 2004, George W. Bush was running for re-election and the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq and its fallout were dominating global discourse. Fahrenheit 9/11 was a visceral and satisfying watch if you loathed the sitting president and his catastrophic war-mongering, as most of the international industry assembled in Cannes surely did (the film received a 20-minute standing ovation, one of the longest in festival history). Even the jury’s arch-aesthetes like Quentin Tarantino, that year’s chair, and Tilda Swinton, bowed to the moment. Both later insisted they backed Moore’s doc for filmmaking reasons rather than political ones. Sure… But so what was the true cinematic discovery of the day? That year Cannes made a rare exception in allowing a young Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy to compete in the festival’s main competition even though it had already been commercially released months prior in South Korea. It’s easy to see why. Moore’s movie, so galvanizing and potent in the moment, has proved utterly disposable, while Park’s revenge thriller is everything you could hope for in a searing cult classic. Packed with iconic moments and weirdly resonant imagery (Choi Min Suk’s deranged hairstyle; the relentless, claw-hammer fight scene; octopi eaten live), the film also announced the creative force of the coming Korean wave. Park has now brought three immaculate masterpieces to Cannes — Oldboy, The Handmaiden (2016) and Decision to Leave (2022) — but has yet to bag a Palme. No surprise, then, that world cinema’s closest heir to Hitchcock is taking his next feature, the black comedy thriller No Other Choice, to Venice this year instead.

“”

-

“”

2022: Ruben Östlund’s ‘Triangle of Sadness’ Over Park Chan-wook’s ‘Decision to Leave’

Image Credit: Courtesy of TIFF Ruben Östlund may go down in Cannes history as his generation’s Bille August, a Scandinavian director whose faddish films won over Cannes juries (twice!) but whose oeuvre has not aged well. Just five years after taking his first Palme with The Square, Östlund was back with yet another heavy-handed, yet oddly toothless, satire on capitalism and privilege, involving a yacht full of 1 percenters who get stuck on a desert island with the help, whom they then must rely on to survive. One jaw-dropping set piece — that yacht puking scene — can’t make up for Triangle‘s long stretches of strident smugness and humdrum humor. Jury prez Vincent Lindon could have picked Park Chan-wook’s film noir masterpiece Decision to Leave — a film whose reputation is assured to only grow with time — but instead picked a comedy that wasn’t funny with a political message so sophomore it makes The Square look like Dr. Strangelove.

“”

THR Newsletters

Sign up for THR news straight to your inbox every day

Sign Up

“”

Source: Hollywoodreporter

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the movies section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.

Related Posts

- ‘Enzo’

Les Films de Pierre Photo Principale

Share on Facebook

…

- Former NFL Player Isaac Rochell Sets Podcast ‘Don’t Worry I’ll Ask’ (Exclusive)

- Inside the Disney Upfront: “Glen Powell, What Are You Doing Here?”

- Rod Stewart and Penny Lancaster confuse fans with photo from ‘romantic’ getaway

- Anonymous No More: Inside the Complicated Life of Harvey Weinstein’s Key Accuser