All 9 of Darren Aronofsky’s Movies, Ranked From Worst to Best

In the year 2000, there were so many hip filmmakers making sexy violent experimental crime fantasias. Darren Aronofsky stood out. Most Sundance debuts were cheap, but his breakout feature looked funded by quarters stolen from a broken vending machine. When other young directors were trying hyper-kinetic editing, he all-but-trademarked the rapidfire split-second montage: heroin, lighter, bubbles, syringe, molecules, eyeball, STONED. Rather than join the long line of provocateurs battling the MPAA over NC-17 ratings, Aronofsky just released his second film unrated — a totemic act of Generation X defiance. And while plenty of awesome movies back then were about drugs, an Aronofsky picture somehow just was a drug: intoxicating, traumatizing, addictive, corrosive.

Twenty-five years ago, the release of Requiem for a Dream cemented his status as a hallucinatory new-millennium visionary. After a quagmire period spent developing and re-developing his hyper-personal cosmic romance, he returned to prominence with a grody wrestling weepie and a lurid ballet horror show. Then he got into global warming. He remains our defining poet of the cinematic extreme, embedding mytho-religious undertones inside visceral cockroach overtones, vortexing his beautiful, doomed protagonists toward symphonic self-mutilation. As Requiem for a Dream celebrates a quarter-century of emotional mayhem, it’s time to embark on an epic journey across time to rank his filmography. Don’t expect too many happy endings. In Aronofsky’s universe, God exists and doesn’t care.

-

“”

The Whale (2022)

Image Credit: A24/Courtesy Everett Collection The most watchable movie ever made about a 600-pound-man dying for a week, this A24 arthouse hit gave Brendan Fraser a comeback Oscar and marked Aronofsky’s independent-film return after a decade spent burning Hollywood cash on eco-fables. Fraser’s depressed teacher Charlie barely leaves his couch, committing slow-motion suicide-by-pizza while loved ones swing through his apartment for sad convos. Some people think The Whale hates overweight people. Allow me to begin this list by wondering if Aronofsky kinda hates everybody — and loves what he hates about us. He films Charlie’s girth with cruel leviathan awe and turns the ensemble into a parade of grotesques. Charlie’s estranged daughter is an internet-youth gorgon. The eager missionary is a homophobic liar. Hong Chau’s nurse enables Charlie as an act of ruinous love, issuing dire heart-failure warnings as she hands him another chicken bucket. Adapted from screenwriter Samuel D. Hunter’s play, The Whale is speech-y and stagebound, lacking the director’s usual rollick. But it’s not here at the bottom because of all the mawkish squalid excess. The problem is the other squalors are more fun.

“”

-

“”

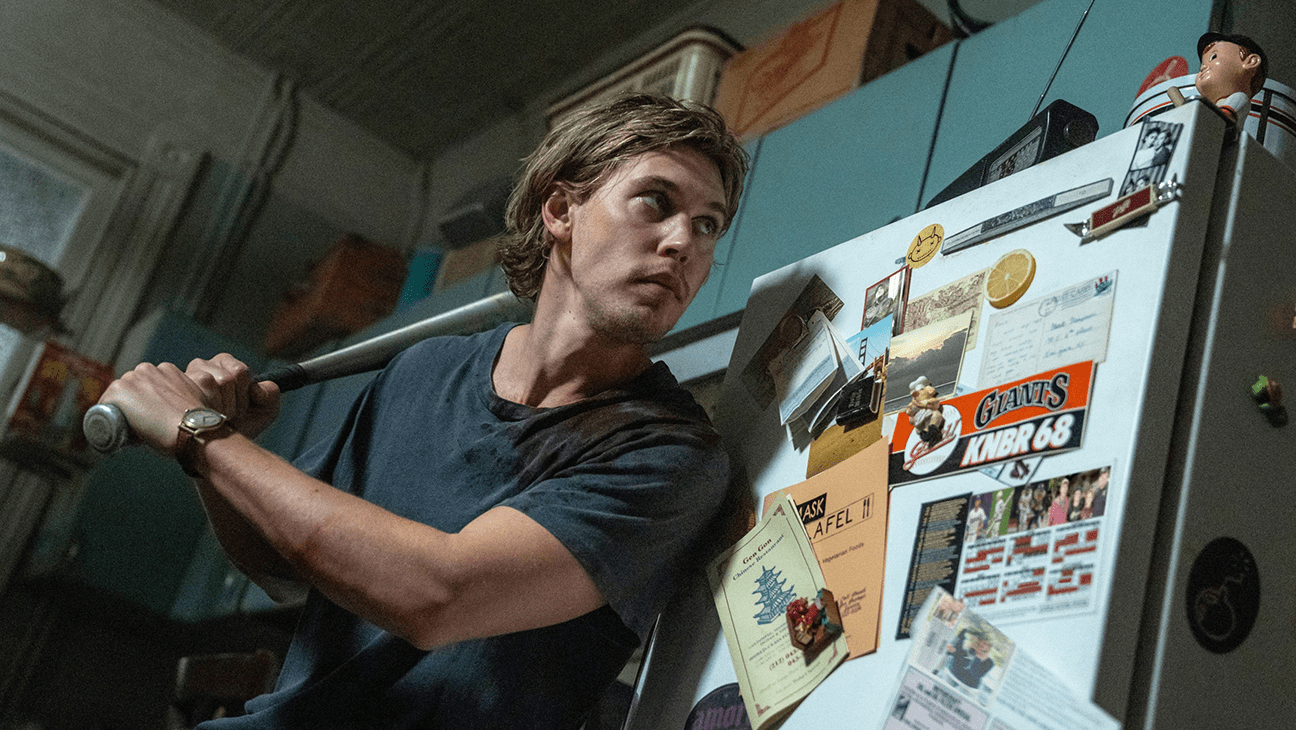

Caught Stealing (2025)

Image Credit: Sony Pictures/Everett Collection Must admit I’ve been worried about Darren Aronofsky for a while now. Beyond The Whale’s Oscar-bait showboating, his other recent projects were smelling like desperation. He produced a couple Disney+ celebrity vanity projects, went to the dystopian Vegas megadome, sold part of his soul to Google. Perhaps we ought to embrace new technologies like spheroid mega-cameras and [deep sigh] generative AI. Maybe he scratched some intense itch sending Will Smith to the bottom of the ocean and forcing Chris Hemsworth to role-play death. Then again, maybe it’s a midlife crisis or a flat-out artistic calamity: two decades of renegade style optimized into semi-parodic Brand Aronofsky for fame-powered corporate collabs.

So it’s notable that this caper attempts to go back to basics. Twenty-seven years after π, here’s another paranoid thriller set in ‘90s Lower Manhattan. Austin Butler’s bartender Hank pinballs between outrageous underworld types: Britpunk, bad cop, Orthodox hitmen, Russian baldies, Bad Bunny as a kingpin, After Hours’ Griffin Dunne as a living symbol of pre-Giuliani downtown entropy. In a weird way, it’s the first normal Aronofsky movie, insofar as the whole New York Chaos Quest subgenre already gave us some Safdie spectacles, a couple John Wicks and Anora. You feel the director, an aging enfant terrible, trying to outdo those upstart sensations for sheer filth. The first time Hank gets into a fight, he winds up pissing blood and losing a kidney. Then someone pulls staples out of his stomach. The trailer promised sizzle between Butler and Zoë Kravitz, but things get brutal fast. Sheer body-count hideousness makes this a solid watch for nutcases. Scrape off the outer layer of vomit gore, though, and you’re left with a pretty straightforward Find the Thing potboiler. Try not to get depressed by this career trajectory. In the actual 1998 of π, characters believed enlightenment was possible. In Caught Stealing’s cynical re-enactment, the best anyone can hope for is a big payout.

“”

-

“”

The Fountain (2006)

Image Credit: Warner Brothers/Courtesy Everett Collection A lot going on here. Conquistadors, murderpriests, a space bubble, a dying wife, Mayans, metafiction, bearded Hugh Jackman, hairless Hugh Jackman, Tai Chi, Eden, a secret pyramid, the Spanish Inquisition. Reduced to its most legible plot points, The Fountain is about a man who injects a tree into a monkey to cure cancer, another man (maybe the same man) becoming a tree (maybe the same tree) to stop Christianity and still another man (who might be first two men) taking another tree (or still the same tree) to a supernova. This timeline-warping epic was supposed to be the post-Requiem studio coming-out party, before Brad Pitt departed the original production to get swole for Troy. “I realized that this story was not going to exit my veins until I did it,” Aronofsky later wrote in the graphic novel version of The Fountain. “I decided to rewrite the script. Make it a mean, lean indie film.”

The result of his labors is a seminal shambles, awesome and boring in equal measure. It’s a sincere love letter to Rachel Weisz, Aronofsky’s then-fiancée, a great performer trapped in Cancergirl tropes (who appears to write a long novel in longhand with no crossouts). The special effects are still awesome. A single scene of mass Catholic torture teases vaster religious infernos to come. A central idea, underlined in the theme-y dialogue, is “Death as an Act of Creation.” The Fountain died a few times — canceled, reduced, finally flopping upon release— but you never doubt Aronofsky needed to make it. Like the proverbial god-tree who feeds its worshippers immortality, he had to get all the sap out of his system. The epics got nastier, and better, from here.

“”

-

“”

Noah (2014)

Image Credit: Niko Tavernise/Paramount Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection Everyone knows about the big boat full of the animals. But did you know Noah hung out with rock monsters, carried shining napalm gemstones, ingested ancient ayahuasca, rocked a buzzcut and slayed some fools with an axe? Here’s the cosmo-spiritual passion project that actually got the big budget, with Aronofsky blowing all his Black Swan cachet on a bummer epic about why God wants us all dead. Somehow, it’s both his global hit and a missing-link curio in his filmography: too religious for hipsters, too green for Christian right-wingers, rife with implications of incest people usually try to ignore in Sunday school. There are bad things (golden angel CGI, bland Emma Watson) and great things (the Genesis-as-evolution sequence, Ray Winstone as a snarly all-consumptive overlord). Somewhere in the middle is Russell Crowe, blending his whisper Gladiatorial eminence with his more recent penchant for overwrought Kraveny ham. I kind of love how metal it all is — like, is Noah gonna kill a baby? — and unfortunately any film about climate change will keep looking better every year our weather gets worse.

“”

-

“”

π (1998)

Image Credit: A24/Courtesy Everett Collection Smart Max lives lonely in a Chinatown apartment full of prescription drugs and computers. He’s seeking the ultimate equation — a pattern hiding within the stock market that will help him decode the universe. This only really needed to be a modest calling-card movie advertising a young filmmaker’s visual panache. Instead it’s an out-the-gate masterpiece, a gutbucket cheapo so eye-popping it wound up playing in IMAX. Garden of Eden, pill-popping montages, gross subway weirdness, Jewish mysticism, Clint Mansell’s music, Matthew Libatique’s cinematography, legendary character actor Mark Margolis: Aronofsky arrived fully formed. As played by Sean Gullette, Max is a generation-defining character. You could argue he’s gloriously carbon-dated to his post-grunge moment, sounding very Reality Bites when he tells a vain Wall Street operative: “I’m looking for a way to understand our world. I’m not interested in dealing with petty materialists like you.” But while all the other indie dude directors were making semi-improvised chillcoms about dudes hanging out, Aronofsky saw the coming century of techno-inhuman obsession. Almost three decades on, what’s not prophetic about an abrasive shut-in brainiac tearing himself and his world apart? We’ll get a spiritual sequel if that Elon Musk movie ever happens.

“”

-

“”

Black Swan (2010)

Image Credit: Fox Searchlight Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection Elsewhere in Manhattan, another outcast genius disappears into different violent transcendence — but instead of math, it’s dancing!! I’m still not sure this best picture nominee is a serious meditation on the self-eradicating nature of art. I do know Black Swan is a horny thrill ride, classy enough for extended ballet sequences, fully giallo in its argument that everyone is either trying to screw or kill each other. Natalie Portman is Nina, the baby-voiced ballerina still sleeping with stuffies in her mother’s apartment. When she seeks the lead role in Swan Lake, her company’s artistic director commanding ever-so-Frenchfully to sex, sex, sex herself up! More intrigue swirls around new dancer Lily, a free spirit whose dark wardrobe and back tattoo contrasts Nina’s white-porcelain perfectionism — because, you see, black is very different from white. Lily introduces herself in a bathroom by removing her underwear and placing her panties in her purse, right after Nina pulls a chunk of skin off her finger. Or maybe that’s all one big hallucination? One complaint a killjoy could throw on Black Swan is how all the Fight Club-y narrative mindbends make everyone around Nina a bit intangible. (I remain semi-uncertain if Barbara Hershey’s concerned mom and Winona Ryder’s veteran dancer are figments.) It doesn’t matter. Watching pristine Portman come marvelously unglued is Black Swan’s entire diabolical allure.

“”

-

“”

Requiem for a Dream (2000)

Image Credit: Artisan Entertainment/Courtesy Everett Collection A good Aronofsky profile will always mention two key biographical points. First, he grew up loving the Coney Island Cyclone. Second, he had a very happy childhood. Both details are crucial in different directions. The roller coaster provides a handy origin for his turbulent style. The non-traumatic youth makes an intriguing contrast to his narrative bleakness. And both backstories explain the apocalyptic romanticism that made Requiem such an arty sensation. It arrived late in the renaissance of druggie cinema. Trainspotting is punkier, Jesus’ Son more authentically meandering, Traffic more journalistic. I don’t think Aronofsky really knew anything about heroin. But those long hours riding the Cyclone taught him everything he needed about a rise and a fall. It’s always a surprise to rediscover how soaringly joyous the opening act of Requiem is. Shimmering Jennifer Connelly, sweet Marlon Wayans and pre-annoying Jared Leto come off like bright nowhere kids, lost in a summertime chemical haze. They’re living in Aronofsky’s most evocative Eden — boss skag, easy money, they’re opening a clothing store! — which is a brilliant wind-up for the hellish horrors ahead.

And only a dedicated mama’s boy could read Hubert Selby Jr.’s original novel and realize the most crucial character in this youthful opioid opera (with full frontal! and an amputation!) is the informercial-loving senior citizen trying hard to diet. Ellen Burstyn makes Sara Goldfarb the ultimate Aronofsky personality, slipping imperceptibly from domestic purgatory to manic obsession into brain-rotted self-destruction. Her performance expands Requiem’s scope, transforming a portrait wasted youth into a tendrilous vision of addiction and delusion.

“”

-

“”

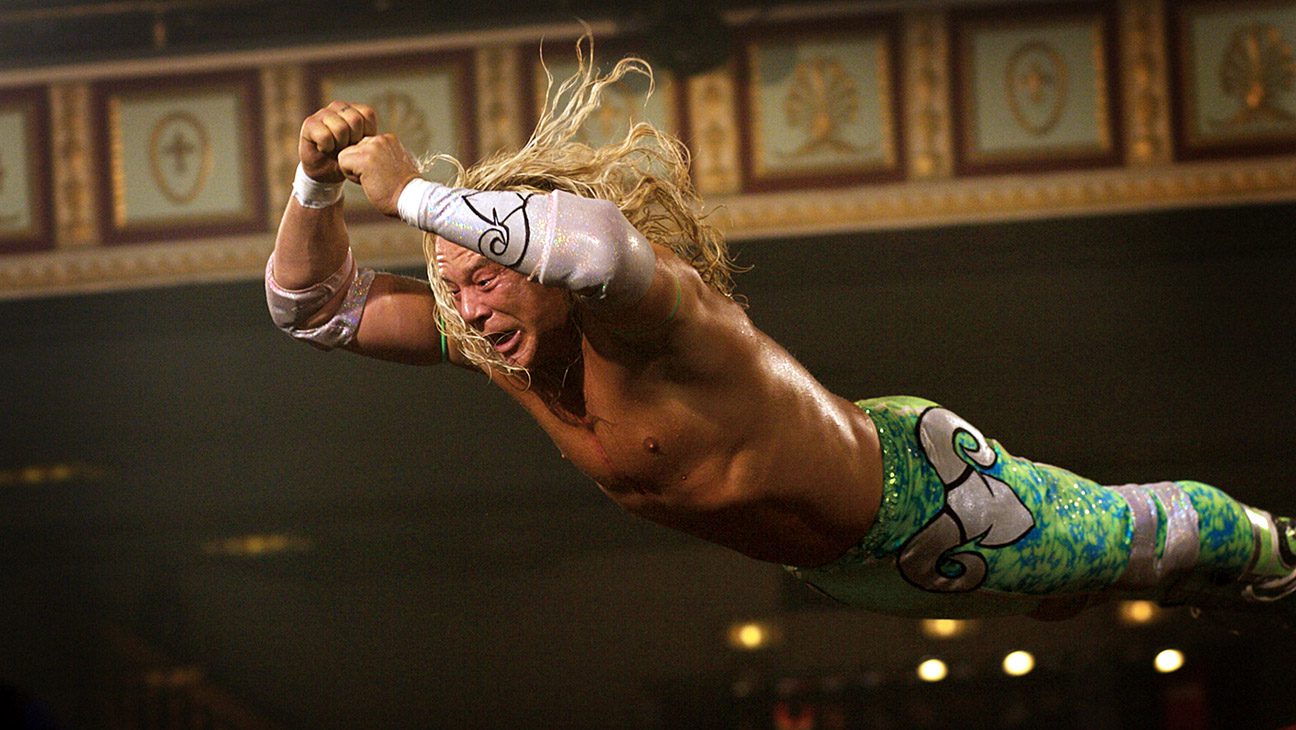

The Wrestler (2008)

Image Credit: Twentieth Century Fox/Courtesy Everett Collection Decades past his prime, Randy “The Ram” Robinson works the backwater wrestling circuit, earning barely enough chump change for strip-club drinks and trailer-park rent. Casting Mickey Rourke as a washed-up star could’ve been a referential stunt. Somewhat unusually for such an ornate stylist, though, Aronofsky seems in awe of his lead performers. (No wonder he’s dated a couple of them!) Rourke can be moving and horrifying in The Wrestler, but what’s most impressive is how the movie resurrects his impish Rumble Fish charm: playing with neighborhood kids, entertaining onlookers at the supermarket deli, talking real-sounding shop with the other fighters backstage.

A handheld-camera portrait of a macho man in decline was a wild swerve from The Fountain’s meticulous dewiness. Free from metaphysics, Aronofsky basks in the pure Jersey of Ram’s day-to-day: the tanning salon, the juicehead gorillas peddling ‘roids, the daytime beers, the ruined old boardwalk and Marisa Tomei as cinema’s greatest exotic dancer. The stars together have an easy chemistry, and if her bombshell single-mom sweetness is a utopian dream of stripperhood, her presence also heightens the inevitable downward spiral. Lest you think this ground-level character study is a bit modest, remember that Ram has a Jesus tattoo and a Job tattoo for maximal spiritual symmetry. Aronofsky’s at his best, I think, when he prisms his celestial ambitions through a down-to-earth perspective. (The only thing better than Marisa Tomei explaining the plot of The Passion of the Christ is Marisa Tomei downing a whole bottle of Rolling Rock.) The Wrestler has a lot on its mind, identifying with documentary precision the precise moment the American psychology split between perpetual Recessionary breakdown and corrosive nostalgic fantasy. It’s also a deeply human magnum opus, by turns sensitive and demolishing.

“”

-

“”

mother! (2017)

Image Credit: Niko Tavernise/Paramount Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection To hell with sensitivity, let’s demolish! In this explosive chamber piece, Jennifer Lawrence is Woman and Earth and Art and You. She’s working on her house; she is her house. Javier Bardem is Man and God and The Artist and You. He loves everybody and will forget them all. Aronofsky’s follow-up to Noah is one of the great cinematic do-overs, reimagining the flood epic’s enviro-spiritual nightmare into a claustrophobic dark comedy of errors. Lawrence plays the nameless wife of Bardem’s nameless writer. Their home is peaceful until it isn’t. Ed Harris is the doctor with a bad cough. Michelle Pfeiffer is his wife, spiking her morning lemonade and scheming for painkillers. Their sons have issues. Nobody respects boundaries. A funeral turns into a rager. Lawrence paints a wall. Bardem writes a new book. There’s a baby on the way. Something gets flushed down the toilet.

Yes, it’s whole entire Holy Bible as a home invasion horror pic, climaxing with enough Book of Revelations carnage to make Requiem’s electroshock look like a spa retreat. The metaphorical reads are bottomless, but mother! belongs on top of this list for the sheer risky highwire act of its cinematic invention. Libatique’s swirling camera makes the house’s interior continentally vast. Bardem is charming and malicious, a rare breed of clueless mastermind. And my lord there’s Pfeiffer, eyerolling through her own Eve-Lilith allegory. There are people who can’t stand any of it, and I understand. There’s no proper musical score in mother!, and Lawrence’s lead performance dims her natural charisma even before the final act’s physical punishments. The film does not resolve all Aronofsky’s complexities — the feeling that he’s somehow a pornographer and a preacher, glorying in transgression while he sermonizes some lessons in morality. All mother! can do is throw the paradox onscreen and slap an exclamation point on the end. What exclamation, though! And what points!

“”

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the movies section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.