An MTV Mogul’s Wild Tales: From Sex Clubs with Sumner Redstone to Advising David Ellison

Despite his 26 years in a traditional media job, ultimately rising to CEO of what was then Viacom, Tom Freston had no interest in writing a traditional business book. Instead, Unplugged: Adventures From MTV to Timbuktu, published by Gallery Books, is a story of one former mogul’s adventures around the world.

“Most people who are executives or have been executives write a ‘how to do business better’ type book,” he explains. “I wanted to write one about how to have a better, more interesting life.”

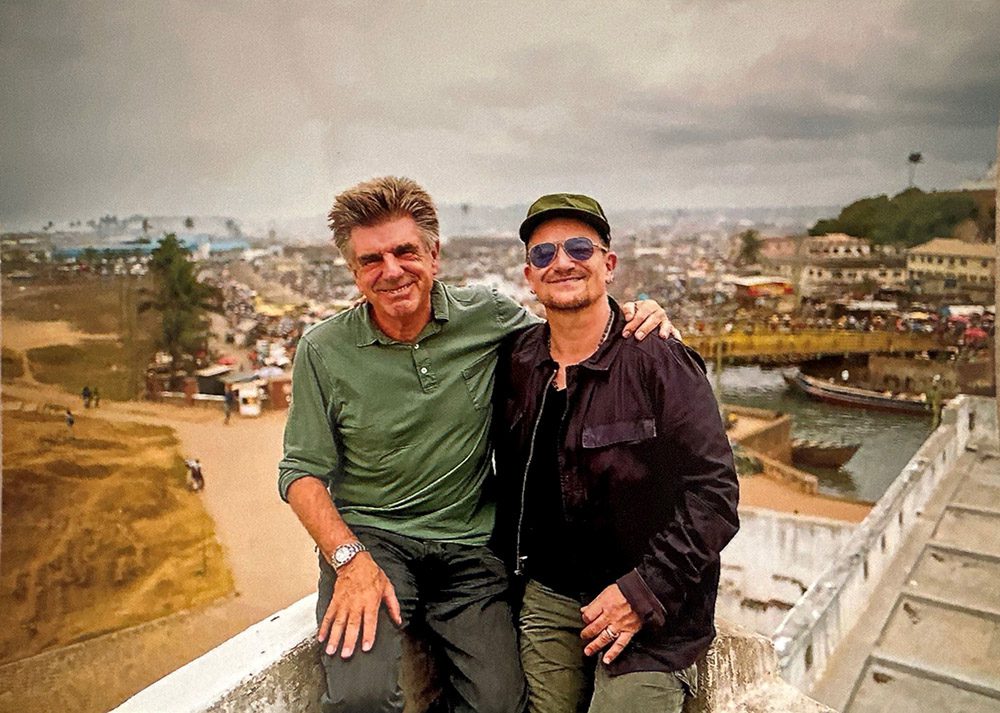

It’s a fitting approach for a man who’s lived as much of his life off the grid as he has on it. The 79-year-old logged years in such far-flung locales as India and Afghanistan, where, at one point, he had a multimillion-dollar clothing export business. He tended bar in the Virgin Islands, built an orphanage in Burma and, later, centered his focus on Africa as board chair of The ONE campaign, an anti-poverty advocacy organization co-founded by Bono, one of Freston’s famous pals.

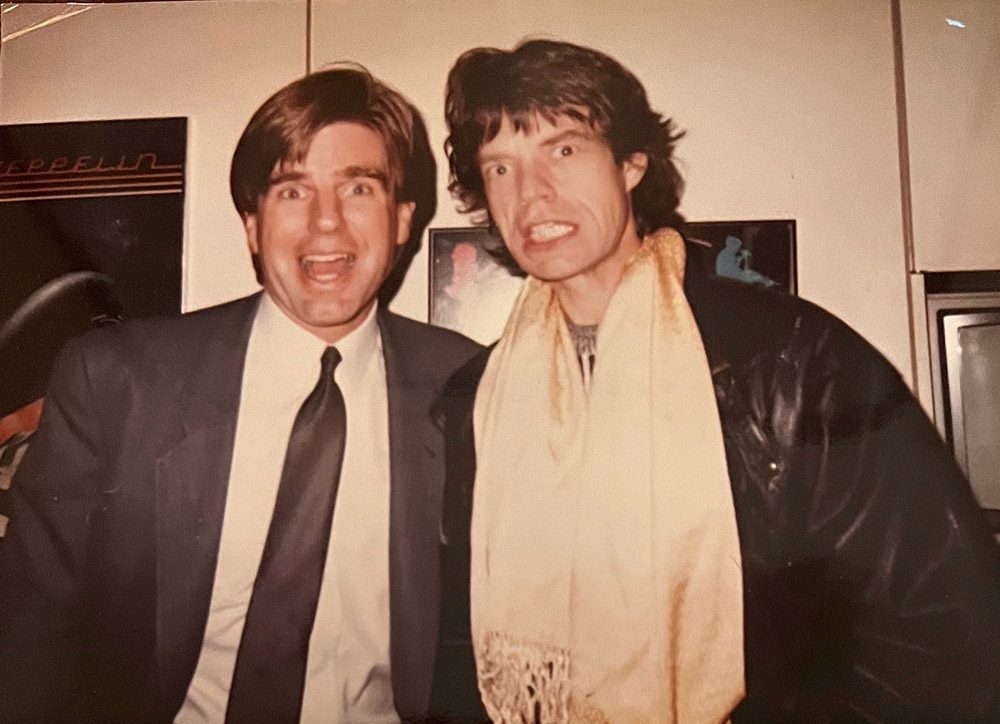

In between, Freston returned to the U.S., and landed a gig at a new, scrappy startup, the Warner-Amex Satellite Entertainment Co., which had just launched two cable networks, Nickelodeon and The Movie Channel. Determined to have cable do for TV what FM radio had done for AM, the company would launch a music channel next, and Freston, a music fanatic, joined its founding team as marketing chief, soon rising to president. From there, he swiftly climbed the corporate ladder, adding other brands like VH1 and Comedy Central to his purview.

By late 2005, Viacom chairman Sumner Redstone, who had acquired the company years before, was so impressed by Freston’s consistent results, he elevated him to CEO. Of course, he fired him eight months later, furious that he hadn’t scooped up Myspace as Redstone rival Rupert Murdoch had, paying $580 million for the social networking service at the time. (When the latter famously collapsed in 2011, Murdoch offloaded it for $35 million; not doing that deal had saved Viacom more than $500 million. As Freston writes, “I’m still waiting for a thank-you note.”)

In early November, Freston, a father of two whose globe-trotting continues, hopped on a Zoom to recount a few of his wildest tales, including an infamous sex tour with Redstone, and sound off on David Ellison, David Zaslav and the fate of MTV.

I can’t remember what I had for breakfast yesterday, and somehow, in your book, you’re recounting conversations you had in your 20s and 30s. Had you kept journals along the way?

When I was living in Afghanistan and India, I did, and they were pretty precise. When I was working [at Viacom], I had a diary and some notes, but when I left, I didn’t take anything other than a few pieces of paper and a chainsaw [a gift from the heavy metal band Anthrax]. That was it. I was gone. But you can Google stuff and try to triangulate and figure out where you were, and then I’d talk to people. It’s remarkable how your memories come back.

I suspect there were some stories that felt like “musts.” One of my favorites is how, in order to get David Bowie to do an “I Want My MTV” commercial in the early ’80s, you flew to Switzerland and met him on the ski slopes in Gstaad. You then proceeded to ski with him, ultimately ending the day in a sauna with him and Paul McCartney.

I’ve been dining out on that story for years. It’s a good one.

I’ll admit I’m still processing another story you share about taking Sumner Redstone and his mistress to sex clubs in Asia. At his request, you’d watch people fornicate onstage. I’m guessing you didn’t need a journal entry to recall that trip?

No, no, it’s still clear in my mind. (Laughs.) I figured that had to go in there. It showed a side of him. On one hand, he’s a brilliant businessman, bold and unstoppable. I mean, who wants to start a conglomerate when they’re, like, 65 or whatever he was? But then there was this side of him that was emerging that I saw. And then, in the end, after I leave [the company], he’s spending, like, $150 million on hookers. I thought, maybe that thing in Bangkok kind of set him off on a new trail.

It’s your fault.

Yeah. (Laughs.) But taking him through there and just looking at the look on his face — I had to get out of there, and he had to move up [to get a closer look]. I hadn’t seen that side of him before because he was always with his wife, Phyllis. I never knew he had this longing.

You also included a wild story about how Comedy Central was born. One day, without any plan whatsoever, you publicly announced you’d be launching a comedy channel, simply because you’d heard rival HBO was doing so.

There were so many Comedy Central stories to choose from, but I thought it would be good just to say how we did it. And what we did is the kind of thing you can’t do these days. “Hey, HBO is starting a comedy channel. Well, we should start one this afternoon. Let’s just announce it. We’ll be in all the news articles.” And it worked like a charm. That thing became worth billions of dollars.

What didn’t make the book?

Well, I wanted to keep a fun tone, so I had a couple of stories [that we cut]. There was one about when I was working in Liberia with ONE and Red, and I met this cannibal warlord guy named General Butt Naked. Then when I wrote it up, it just was a downer. The guy killed, like, 10,000 people, ripping hearts out of kids. There was another one about when I brought a case to the Supreme Court for special needs kids, for my son, but it just didn’t fit. [My editors] were like, “Hey, keep it at 300 pages. You’re not Barbra Streisand.”

As you write in the book, you got your job at MTV because Bob Pittman liked your checkered past. In fact, he was convinced you’d been a hashish smuggler.

Yeah! He recognized I had done other things, too. He wasn’t just like, “Oh man, let’s get a dope smuggler in here.” (Laughs.)

Of course. But I’m curious how you think your lack of a traditional path or any TV experience, for that matter, served you in that job?

They wanted untraditional people. Same with the people they hired for Nick — they were, like, schoolteachers. No one had come from TV. Because we were inventing it from the ground up, so there was no legacy. You could be scrappy and open to different ideas and a little edgy. And we had fun. Those early days at MTV, everybody was a music fanatic and no one really cared about how much money we were making, which is a good thing because no one was making any. But even now, whenever I run into somebody, they say how much they loved working there. We have a Facebook group called, “I worked at MTV when MTV was cool.” I mean, people couldn’t wait to come to the office in those days. They would sleep there.

Well, yes, there were also hookers and tequila girls and whatever else was going on in those offices.

We had a receptionist who sold cocaine, but he didn’t last that long. (Laughs.) That was the ‘80s!

Are there moves you wouldn’t have made had you come in with traditional TV background?

Yeah. When we’d get thrown off cable systems, we’d go full blast. I mean, we’d fly Don Henley and John Mellencamp to Denver to the TCI headquarters and we’d try and rabble-rouse these bottle-wielding youths, who were our fan base, to storm the cable system. And we’d always get back on. I saw that recur in the Jimmy Kimmel episode.

How so?

Everyone talked about “Poor Bob [Iger],” who I love, but the missing piece of the equation was the young fan base that’s rabidly in love with Jimmy Kimmel. You don’t just take something away from them. They’re going to hurt you, reputationally and business-wise. You saw that: They canceled all those Hulu and Disney+ [subscriptions]. And that was not in the equation. It was like, “Well, do we listen to the FCC? What do we do? We don’t want Trump [to retaliate].” But to get back to your question, [we probably would have been more concerned about] offending our distributors instead of just burning down their cable system or having a rock band out in their parking lot.

You ultimately rose to CEO of Viacom, but that was never a job you wanted.

I was in an imaginary world, thinking I could stay where I was. I wanted to be like Lorne Michaels, who’s seen 50 regimes come and go and he’s still there doing his thing. Everything I loved was at that company, and when I moved up, I knew what would happen. I mean, you’re dealing with serious business — with Wall Street and bankers and financial statements. Not that I don’t know those things, but it wouldn’t be as enjoyable a job.

Have you ever regretted accepting the job?

No. Because if I hadn’t taken it, I’d be working for Les Moonves. And who knows where that would lead me.

Presumably out the door.

(Laughs.) By the way, Les and I always got along pretty good. But by [the time Redstone approached him about taking over for Mel Karmazin], I’d been there for, like, 20 years, I was around 60, and I figured being the head of a public company is a big honor. Who would’ve thought I’d be ringing the bell on Wall Street? So I decided I wanted to do it, and then the funny thing was that I’d told Sumner I needed 24 hours to think about it, and then when I came back to him to say yes the next day, he said, “I already gave the job to Les.” I was like, “It’s only been 17 hours!” [Redstone ultimately made Freston and Moonves co-presidents in 2004; by late 2005, he split the company in two and named Freston CEO of Viacom.]

It sounds like Paramount chief David Ellison is going to make a go at rebooting MTV. How would you approach that? And is it even possible?

I think so. I had a meeting with David and Jeff Shell and a couple people. They had a lovely dinner — me and [former colleagues] Judy McGrath and Doug Herzog and Jason Hirschhorn just before they made the purchase. It was due diligence on their part. They were like, “You guys were there in the golden age. We don’t know what’s happened?” I said, “First of all, when they sawed the ‘music television’ off the bottom of the logo, they lost me.’ But all the music people had left and MTV didn’t have any real value as a music brand. I don’t know if you can resurrect it, but I think you might be able to.

One, they have a huge library of shows. The Unpluggeds and some of the reality shows were pretty good. They also have a huge library of music videos and MTV News — everything that happened from 1980 on. So, why couldn’t you do some kind of digital curation thing? Anyway, I’m really happy to see Ellison there. I mean, if someone was going to buy Paramount, the Ellisons got my vote.

Why is that?

He loves movies. He can make movies. He’s proved himself, and he’s got a lot of money. If a private equity company came in there, they’d sell it for parts, and it would disappear. Ellison will have to go through some rough times now. They have to cut costs. But my hope is that they’ll be able to attract more smart, creative folks to take it to a new level. And the options were not good for anything else as far as I could see.

What did the new leadership team ask of you?

It was like, “If you were me, what would you do?” But first, they laid out the situation as they saw it. “We’re going to have to face some tough cuts. But we’re buying this company, we don’t want to spin it out into one of these Shit Cos., as people call them. We’d like to see if we could resurrect [the brands], and what ideas do you have?” And yeah, they’re asking a bunch of older people how to make it a cool, fun place to work and have a good business plan that people could line up and salute — but at least we’ve been there. Of course, the answer is you really should tap into young kids and find someone like John Mayer. He has this amazing channel on Sirius.

John Mayer is approaching 50 …

But he’s still young, and he could still have ideas. And he’s better at directing some 20-year-olds than we would be!

Looking out at the entertainment landscape, who’s doing a good job right now?

I admire Bob Iger, like everyone. I love the folks at Fox Searchlight. They’ve still got spunk. They still find the right thing. Those guys are curators. I love A24, they find something with some edge, and they’re able to mainstream it in their own specialty-label way.

You famously got fired by Sumner for not buying Myspace. Can you describe the emotional whiplash that must have occurred between your firing and the flash mob of sorts that occurred in the lobby as you exited?

I was humiliated and depressed. I was leaving this thing that I loved, and we were just getting going. I’d seen him fire both Mel Karmazin, who was wonderful, and Frank Biondi, who was fantastic, for doing their jobs. They were making smart moves, and they were getting credit. So, I packed up and I thought I’d just sneak out, get a taxi and go home. Then the elevator door opened and I couldn’t believe it. It was packed, and it was a big lobby, and they started chanting my name. I mean, they followed me out the door. “Tom! Tom! Tom!”

What was going through your head at the time?

Everything was in slow-mo. I started to well up — all the people I love, they were all there and touching me. It was like I was some rock star. And then they aired it on CNBC. I guess it was validation. Because I’d had imposter syndrome, and I’d thought, “Oh fuck. They finally busted me. I’ve been faking it all these years, and now I’ve been caught and I’m going to leave in disgrace.” Then all of a sudden you get this hero’s sendoff, and it was extraordinary. It was probably one of the greatest moments of my life.

You’d mentioned in the book that one of the first people you heard from was Tom Cruise, whom Redstone claimed he had fired as well.

And Tom didn’t even work there! Yeah, he called up, and I had a good relationship with Tom. He’s a lively, friendly guy and he was the backbone of Viacom, and then he’s getting humiliated by Redstone for no good reason. [In 2006, Paramount Pictures terminated its 14-year relationship with Cruise over his offscreen behavior, notably the couch-jumping incident on Oprah.] So, we both just laughed. And Tom was very kind, he said, “I’m sorry to see you go,” and I think he was sincere.

You were approached about a lot of different traditional CEO jobs after that but opted to take none of them. How come?

I didn’t know at first. I took my friends and my wife on the “Tom Got Fired” tour to Burma. It’s a beautiful place, and there was no media there. At the time, I had my lawyer saying, “You better get another job right away or you’re going to be gone.” It was Bob Pittman who said, “You’re in no condition to make a decision right now. Go away and clear your head, and if you come back, I’ll give you an office in my new place and you can figure out what you’re going to do.” Bob gave me the permission to go and I did, I got clarity. I realized, I’d done this for 26 years, why not do a portfolio of things next?

I was never into the job for money. I mean, I got a nice goodbye [$84.8 million, to be precise], but I figured I don’t need to be grafted on top of a company like Yahoo that I didn’t build and had no connection with. So, I went back to Afghanistan, which was exhilarating and meaningful because the networks there were all about socially connecting the Afghans to the world and to each other, gender equality, all these things that you sort of believe in. And I worked with Oprah. I went in with Vice. I was on the DreamWorks board. It was a good mix.

In many ways, your involvement as an investor in and adviser to Vice legitimized the company and its larger-than-life leader, Shane Smith. You’ve said that he’d call you his mentor, but he was a difficult protégé. Is that right?

Oh, Shane’s his own man. No one’s going to be a mentor to Shane. I got to say, I love him, still. He could sell ice to the Eskimos, that guy. And the HBO show that we did was exhilarating. We were going everywhere, doing everything, and Shane was great at piecing these stories together. That was really fun for me. They were building their own little MTV Networks. But at the end of the day, they ran into the same head-on winds that the cable networks did, which was, even though they were digital, all the digital publishers ended up following the cable networks because Google and Facebook were taking, like, 90 percent of the money. They’re like vacuum cleaners.

Presumably there was advice you were giving Shane that he wasn’t taking?

Yeah. I said, “You sure you want to start a TV network? They’re kind of going out of style, these linear networks.” But he was always on a quest for a bigger deal and more money. And he’d convinced all these people to partake, and he was making good stuff, it just wasn’t profitable enough, particularly when the revenue started to drop. But I had a lot of fun with him. And I’d run into him everywhere. He liked all the edgy places.

Are you two still in touch?

I’ll still get a text or two. They come at, like, 5 in the morning: “Hey, buddy. I love you.” And you go, “Oh, it’s Shane.”

When Paramount Pictures came under your purview, you’d go to Bob Daly’s home in Bel-Air a few times a week and, as you put it, you became a student at the Bob Daly Film School. I’m curious what the Tom Freston leadership school curriculum would entail?

I’d have to be a professor emeritus at this point. But I’d try to teach people that it’s about risk-taking — while still keeping your costs under control. So, let’s not get ahead of your skis, but take risks. Look to the edges. I was always a proponent of operating out of the mainstream. I don’t want to be going head-to-head with all the major studios or all the big cable networks. If I could be No. 1 in some category over on the left here, I’m removing myself as much as possible from the forces of supply and demand. And then fill it with a creative group of people and make it a place that they want to come to work and where their work would be noticed and rewarded. Is that still possible today? I hope so.

Beyond Ellison and Shell, how often are people still calling you for advice these days?

Oh, it’s decreasing at an increasing rate. (Laughs.)

You don’t get calls from the Zaslavs of the world?

Oh, I speak to Zaz. He and I kind of came up together, and now he’s the man.

What would you do if you were him?

I guess you sell [Warner Bros.] for the highest price. I got to give credit to David, though. He went out to Hollywood, and he indicated a love for the form and actually made real friends like Spielberg out there. That’s a hard cult to break into, and he did it.

I imagine in writing this, you thought a lot about your own legacy. Where did you land?

I think I did some good, and I had an innovative, creative life. I certainly took a lot of left-hand turns, and if there’s a lesson to teach younger people, it’s that you don’t have to stay on the straight and narrow, particularly when you’re young. Travel is the best classroom, so get out in the world and look around. You see too many kids today, they get out of school and a week later they’re working at Goldman Sachs or wherever, and they’re having panic attacks and depression episodes. It doesn’t have to be that way. You can improvise your own life. I’d like to be an example of someone who did that and it paid off.

This story appears in the Nov. 19 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the TV section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.