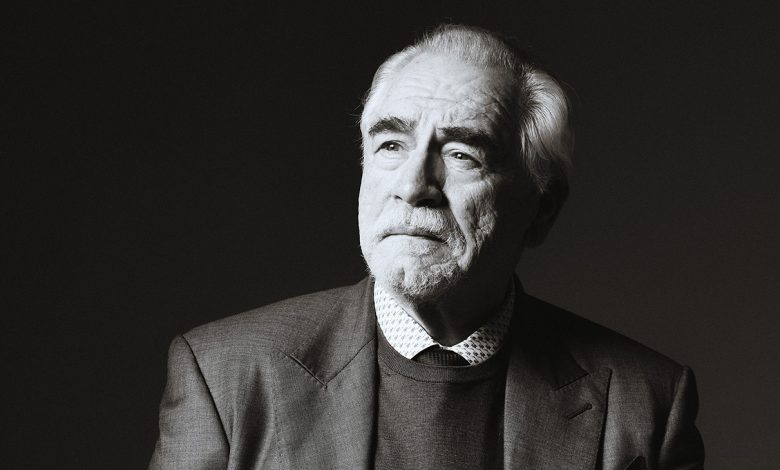

Brian Cox on Kevin Spacey, Jeremy Strong & Why Oscars are ‘Nonsense’

Before 2018, Brian Cox had a pretty good life as a respected, much utilized, but not exactly famous veteran stage and film actor of six decades. And then Succession debuted, the HBO show in which Cox played the snarling, hilariously profane Rupert Murdoch-like Logan Roy, and suddenly, in his 70s, he couldn’t walk down the street without being recognized — often by a fan wielding a phone requesting a “fuck off” to share with friends and followers.

Cox was raised in, and in many ways by, the theater. Marooned in Scotland with his mentally fragile widowed mother, he escaped at 14 by sweeping floors in the Dundee Repertory Theatre and just six years later was performing the Bard’s words on the West End. By the mid-’90s, he’d earned his place in Hollywood as a reliable go-to for directors seeking a grizzled badass with Shakespearean gravitas.

Since Succession‘s end, Cox has been enjoying some career perks, such as the plum gig voicing the fearsome king of Rohan in December’s The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim, an anime prequel to Peter Jackson’s six films based on J.R.R. Tolkien’s novels. “It actually had nothing to do with Succession,” says franchise producer Philippa Boyens of casting Cox. “It had everything to do with Brian’s Royal Shakespeare performance of Titus Andronicus in the ’80s. It had similar echoes of this heroic character, driven mad by grief, fueled by impotent rage.”

As with any working actor, Cox — a thrice married father of four — has experienced his share of workplace grief and rage to draw on for that role. But looking back, Cox says, “On the whole, I’ve been blessed a lot of the time.”

Do you remember the moment you realized you were famous?

It was 2019, and I was playing LBJ [in Robert Schenkkan’s The Great Society] at Lincoln Center. One of the first nights I came out of the theater, this couple who couldn’t have been older than 17 and had their devices with them said, “Could you tell us to fuck off?” And then subsequently, there were more people coming throughout the week, saying, “Tell us to fuck off.” And I realized, “Oh, I’m well known now.” I realized at my late age just how much I thrived on my anonymity. I can’t do public transport anymore. I can’t do things which I did in the past. So it’s a little tough in that sense.

Care to guess how many times you’ve said it for people?

Thousands of times.

What’s the most valuable lesson you’ve learned about show business?

Treat it with all the suspicion it deserves.

You grew up in Dundee, Scotland. Your father died when you were 8, leaving your family penniless, nearly starving. And then, after this, your mother had a series of mental problems that led to her hospitalization. You wrote in your memoir that you witnessed her attempting suicide.

I may have dramatized it. She may have just been cleaning the oven. She was a Catholic, so I’m not sure suicide was an option. She was in a very sad state, my poor ma. She really was.

But how do you reckon this difficult childhood affected how you approached your career?

It made me realize at a very, very early age that I have to depend on myself. Some survival mechanism kicked in that just makes me go, “That’s fine.” My life has given me these little hurdles that I have to get over, and I get over them. I had a horrible childhood, but then I started in the theater when I was 15. I went to drama school when I was 17. Everything fell into place in an extraordinary way.

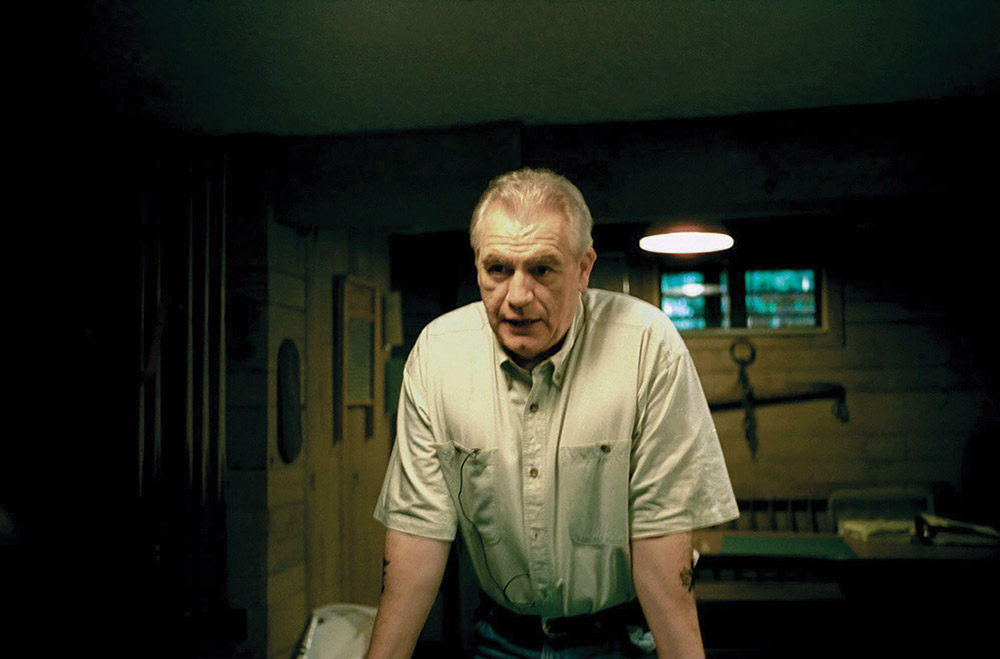

I had certainly seen you in films before, but I think that I only learned your name in 2001 after seeing you in L.I.E., in which you play a former Marine who picks up teenage boys at highway rest stops. You’re amazing, but exceedingly creepy. I rewatched it last night, and my wife, knowing that we were going to speak today, started asking me all sorts of questions about your personal life. You were a very convincing molester.

I was advised not to do that role by some people, but I believe in the human dilemma. You say, “Oh, what a creepy molester character he was.” My desire for [that character] was the fact that he wanted to be a parent. But of course, that’s the difficult thing because there’s also this other sexual thing. I discovered that about chicken hawks — they’re interested in boys between 14 and 18, and once they become 18, they’re too old. The thing about that film, when people really say not to do something, immediately I will do it.

You’ve described having occasionally had a diva moment. Is there an occasion where you look back and think you’d have been better off had you just kept your mouth shut?

Everything’s about this cancel culture now, and everybody’s obsessed with this whole thing about how you’re supposed to behave. I just did A Long Day’s Journey Into Night in London, and in rehearsal, I got very angry at myself. I always get angry at myself when I’m learning my lines. So somebody reported me to Equity here in the U.K. for getting angry. I just thought, “Who was I angry at?” I wasn’t angry at anybody in particular. I was only angry at me trying to deal with this fucking difficult play! It’s just bizarre nowadays. Nobody knows how to be spontaneous anymore.

You mentioned cancel culture. You did a film in the ’90s with Kevin Spacey (1994’s Iron Will). Actors like Liam Neeson have said it’s time to allow Spacey to work again. You wrote that you thought his behavior was a little unseemly when you worked with him, but where are you currently on this issue?

I just think Kevin had certain things which he couldn’t or didn’t admit to, and I think it was a strain on him in many ways. And for me, that was Kevin’s only difficulty. But he’s a very fine actor, and I like Kevin a lot. He’s very funny. I met with him recently. I think he’s been through it. He’s had the kicking that some people think he deserved. He’s ready to get back in the saddle again, and people are trying to stop him from doing that. And I really do go back to, “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone.” Maybe he got too out of hand, but I don’t think he should be punished endlessly for it. There should be a case of forgive and forget. Let’s move on. I think he should be given the opportunity to come back to work.

If someone came to you and said they were going to work with the following actors, what would you tell them? Nicolas Cage, with whom you acted in 2002’s Adaptation.

Just realize that you’re going to be on a wonderful, wacky journey. Nick really is very modest, but he has his own sensibility. And we had the best time ever on Adaptation when [as screenwriting teacher Robert McKee] I had to insult him, saying, “You know nothing about fucking life.” I’ll never forget the look on his face as he stood there and took it, sort of shocked and bewildered at the same time. He is extraordinary.

How about Steven Seagal, with whom you acted in 1996’s The Glimmer Man?

I don’t want to damn the guy because everybody’s getting damned these days, but I remember we were doing this scene and we did the close-ups, and then the director said, “Steven will not do the offlines with you. Is that OK?” And I said, “Oh, I’m so relieved. That would only be a distraction.” There’s a great dichotomy in Steven. He’s a Buddhist, but he’s a Buddhist with an ulcer. My sister used to go to these tae kwon do classes before he was acting, and she said he was very nice. But this business can make you a little wacky sometimes.

And Daniel Day-Lewis, with whom you worked on 1997’s The Boxer?

Dan’s a very nice man, but his method of preparation is entirely different from mine. I don’t believe in getting that absorbed in a character because I believe it’s an ensemble art form, not an art form for one person. It was difficult for Emily Watson, because Dan would speak in the Northern Irish accent offscreen. She didn’t know if she had to respond in a Northern Irish accent offscreen. She said, “So how do I talk?” And I said, “Just be normal. This is Dan’s thing. Just be who you are.” That’s his method. It’s sometimes a little off-putting, but it’s different horses for different courses.

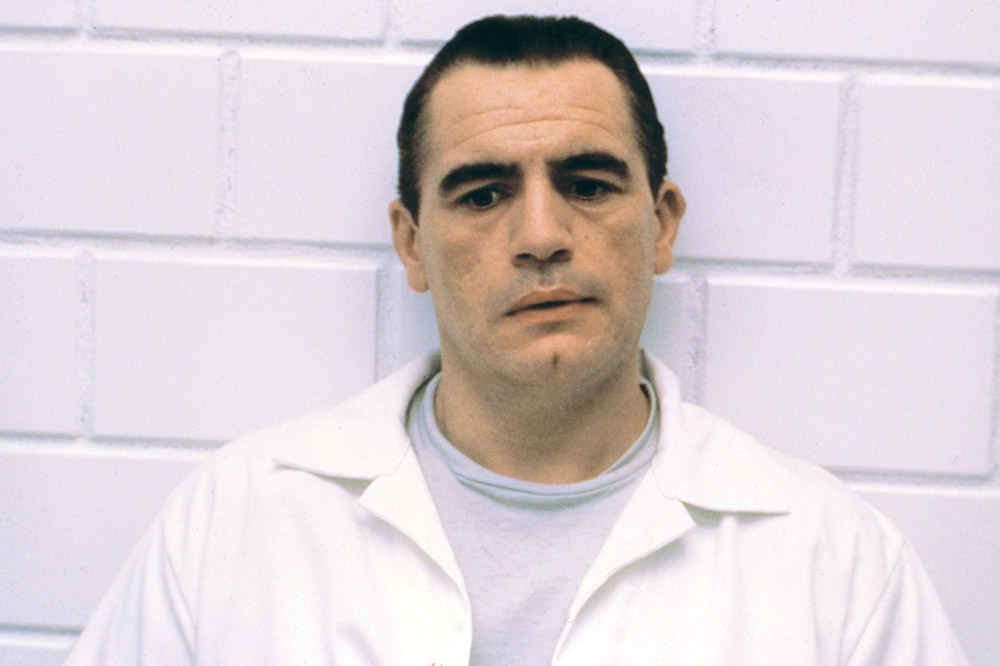

You played Hannibal Lecter in Manhunter in 1986, then Anthony Hopkins played him five years later in The Silence of the Lambs. Care to compare the quality of the performances?

Well, it’s a different character. I mean, it’s like playing Hamlet. Everybody’s going to have their own Hamlet. I chose to play it the way the director Michael Mann and I decided to play it. Tony played it brilliantly. I mean, I had to go to Paris to see it because I couldn’t bring myself to see it in London.

Wait. You couldn’t go to a theater in London to see it?

Because people knew that I was the other Hannibal, and I was worried about them saying, “You’re comparing Hannibal Lecters” and all that. But we played it the way we played it. Tony decided to take it down another route. And of course, Tony’s was a huge success, and he got the Oscar and he made a lot of money out of it. I made something like 10 grand.

Have you never discussed it with him?

We do not discuss it. I’ll tell you why. I did an interview with a newspaper, and the headline in the newspaper was that I was the first Hannibal Lecter. Well, that was true, but it sounded like I was boasting about it and I wasn’t. And then I woke up one afternoon and the phone started ringing and all hell broke loose. Tony and I used to share the same agent, and Tony’s then-missus rang my agent and said, “Tony’s a bit upset about that.” So I rang my agent and I said, “Look, I apologize.” Tony and I have worked together a couple of times since. We never talk about it. And that’s a rule that we never would.

Your 1987 portrayal of Titus Andronicus for the Royal Shakespeare Company was a sensation and has been called the authoritative interpretation of the role. It’s incredibly violent. By my count, there are 14 murders in it. Just how shocking was this production?

People were carried out of the auditorium. I think the first Saturday matinee, we had about eight people carried out because it was too much for them. And when I broke Lavinia’s neck, I had somebody behind me snap a twig, and the whole audience would go, “Oh!” I remember also one night there was some [audience member] who had an accent, and she was going, “Help me, help me, help me.” And I sort of continued talking, took her by the hand and led her gently to the vomitorium [a bathroom offstage]. I’ve never been involved in [another] play where I had that sort of visceral reaction from an audience.

You were so associated with the role. Were you upset when Julie Taymor hired Anthony Hopkins to play him in her 1999 film Titus?

Well, that’s the story of my life. I’m used to that. I never saw the film, but somebody told me she uses the breaking of the neck thing, which I did first. So it’s just the way people are. People steal, what can you do?

And then in 2017, you played the title role in Churchill beautifully the same year that Gary Oldman played the same role in The Darkest Hour — and then got the Oscar.

Our film came out in the summer, and it was a relatively independent film, so you haven’t got the power of the studios behind it. The Oscars are absolute nonsense because everything that’s judged in the Oscars, it’s not a year’s work. It’s just the work that comes out between Thanksgiving and Christmas. I think it makes those awards a fallacy quite honestly because there’s a lot of other good work that goes on outside of what they call Oscar season. So my film never even got a look, and I still think my performance is a better performance.

After the release of that infamous 2021 New Yorker profile of Jeremy Strong, in which you were somewhat critical of his process, you still had to shoot the final season of Succession. Was it awkward returning to set?

We just got on with our job. We get on with what we’re doing. We’re not going to buy into that thing with Jeremy. Jeremy was Daniel Day-Lewis’ assistant. So that is where you can see a massive influence on how Jeremy prepares for his work. But to act with Jeremy is extraordinary. He’s a great actor. I just think the way he works is not the way I work, in the way that [how] Dan Day-Lewis works is not the way I work. Again, it’s horses for courses.

If I told you that you were going to be saddled for the rest of your life with one of your Succession children for Christmas, which would you choose?

It would have to be Kieran Culkin [Roman Roy]. That boy has been through so much with his family situation. And he’s a consummate actor. He really is. And he showed it. He was so nervous when we started the show. I have just watched him grow over the time, and I have such enormous respect for him. He’s a very fine actor, he’s funny and he’s very sweet. And Sarah Snook [Siobhan “Shiv” Roy] would be a close second.

This story appeared in the Dec. 13 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Source: Hollywoodreporter

Related Posts

- Roundball Rocked: With NBA Return Looming, NBC Purges Scripted Roster

- SoundCloud Says It “Has Never Used Artist Content to Train AI Models” After Backlash on Terms of Service Change

- Fox News’ Camryn Kinsey Is “Doing Well” After Fainting on Live TV

- Kerry Washington and Jahleel Kamera in 'Shadow Force.'

Courtesy of Lionsgate

…

- This Alternative Artist Landed a Top-20 Chart Debut With an Album Made Almost Entirely on His Phone