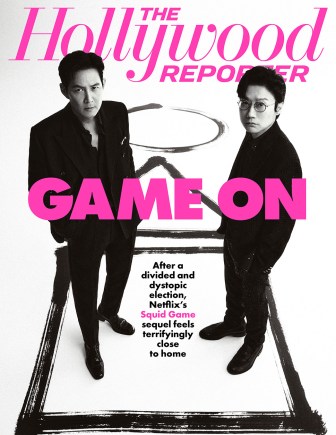

Creator, Lee Jung-jae Tease Show’s Relevancy

A population riven in two, but bound to the same fate. Individuals whose identities are reduced to the faction they’ve chosen, red or blue. And the bitterly contested stakes: prosperity or death.

Sound familiar?

“I want to highlight the theme of taking sides,” Squid Game creator Hwang Dong-hyuk says of the major motif for season two of his international hit series, in which people in personal financial crisis engage in a battle royale for the chance to win a life-saving sum of money. Hwang is standing in the show’s enormous dormitory inside the belly of Studio Cube, Korea’s largest production facility, about 100 miles south of Seoul. While the familiar set still features rows of bunk beds stacked halfway up to the ceiling like scaffolding, it’s impossible to overlook a new feature: a giant blue “O” and red “X” illuminated on the floor, with corresponding blue and red lines bisecting the room.

Though it is November 2023, with the U.S. presidential contest still a year away, Hwang knows that season two will drop around the time of the election — which he calls “the ultimate O-X event.” He also notes that sectarianism is universal. “In Korea these days, we’re seeing much worse conflict between the elderly and the younger generation. And you see demarcation everywhere. There’s no room for debate, only hostility. So I was inspired by the direction the entire world is taking.”

As Netflix’s most popular title of all time, Squid Game already was arguably the most anticipated returning show on the planet. But in the wake of the fractious U.S. presidential race whose outcome has revealed intractable social fissures and has left at least half the citizenry feeling like dystopia is nigh, it has perhaps also become pop culture’s most urgent and salient work of art.

“I was inspired by the sheer fact that everywhere you turn, people are drawing lines, whether it’s by generation, class, religion, ethnicity or race,” Hwang continues. “I wanted to tell a story about how the different choices we make create conflicts among us and to open up a conversation about whether there is a way to move toward a direction where we can overcome these divisions.”

In season one, after the shocking bloodbath in the “Red Light, Green Light” opening round, the surviving players were given the option to end the game for everyone by majority vote. (The yays had it by one, but nearly everyone opted to return after just a few days back in their regular desperate lives — the show’s most damning indictment of modern society.) This time, the vote to continue is mandatory after each round, and it divides players into clearly labeled camps. One side is motivated by economic anxiety and the belief that they have the qualities to prevail over the rest, winner take all. The other pleads that a vote for the opposition will lead to everyone’s certain destruction.

“We live in a democratic society, and everyone has their own right to vote, but the dominant side rules,” says Hwang. “So I also wanted to pose the question: Is the majority always right?”

***

Netflix’s initial expectations for the first season of Squid Game were modest. “It was always a really big tentpole title for the Korea team,” says chief content officer Bela Bajaria, who was the streamer’s head of global TV at the time. “We knew it would be very big in Asia, so the marketing campaign was all about that.” The most telling indicator of the platform’s projections beyond that region was its release date: Sept. 17, 2021 — just two days after that year’s Primetime Emmys ceremony, hardly anyone’s ideal window for capturing voters’ attention and enthusiasm for the next awards season. By contrast, season two has been given the best possible lead-in Netflix has to offer: the debut of its long-awaited NFL games, which will exclusively stream live and worldwide on Christmas before viewers can binge the seven new Squid Game episodes the next day.

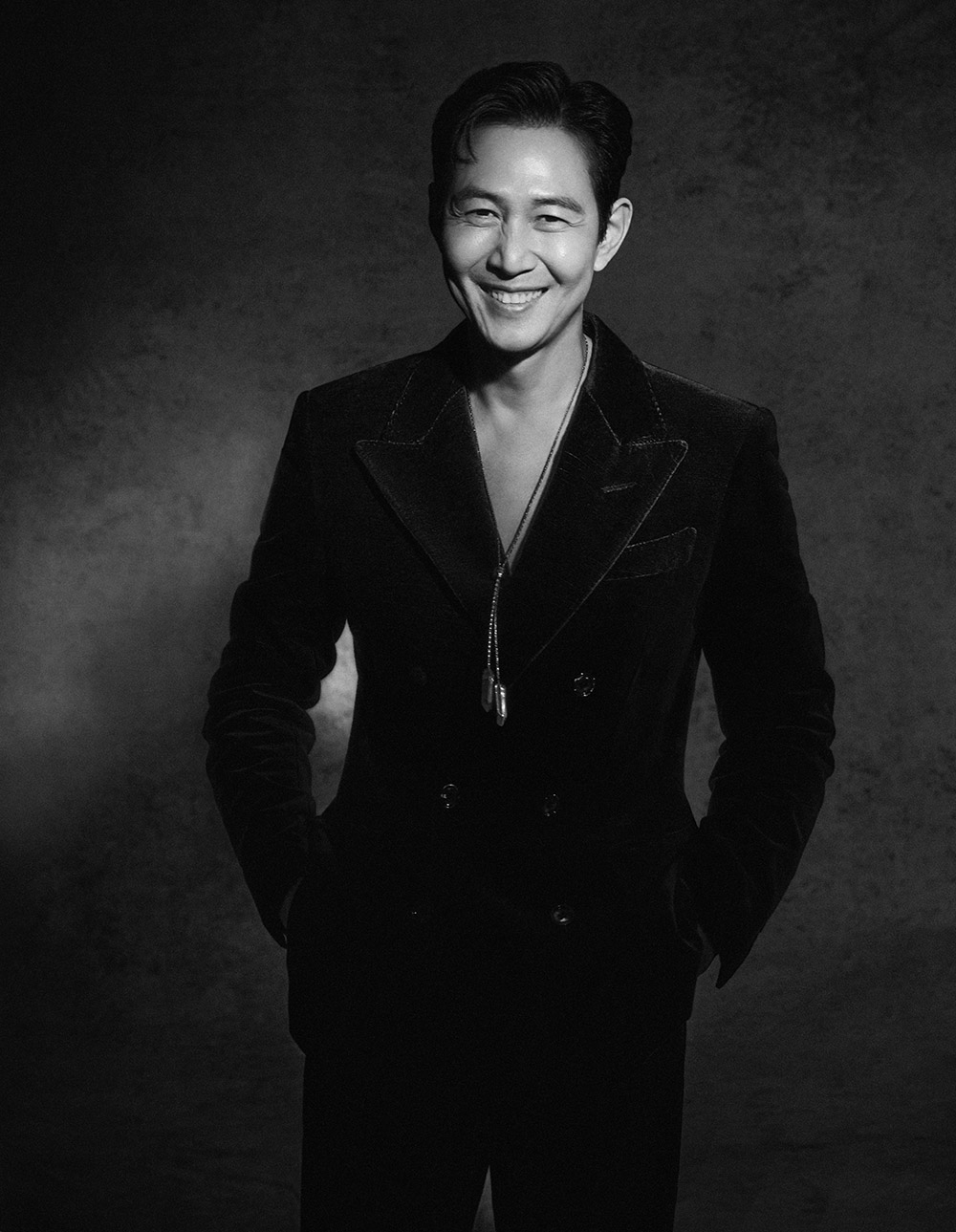

Despite its quiet debut, the show tapped into the zeitgeist of a global, late-stage capitalist society emerging from the pandemic, marrying culturally specific yet universally relevant social commentary with an ironic, iconic visual design (deadly childhood games in a brightly colored, geometric playhouse of horror). Major characters included a Pakistani migrant worker, a North Korean defector and a protagonist, Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae), whose backstory of misfortune was inspired in part by the real-life 2009 Ssangyong Motors strike that was violently suppressed by police and left thousands of former employees financially ruined and dozens driven to suicide.

Thanks to word of mouth — as well as Netflix’s model of making international content widely accessible (the platform offers subtitles in up to 37 languages and dubbing in 34) — the Korean thriller rapidly caught fire. It took just 12 days to become the streamer’s most popular release ever — today it still edges out well-marketed series based on big IP (Wednesday) and from big-name creators (Bridgerton) — as it topped Netflix’s most watched charts in 94 countries, including the U.S. Per Nielsen, the nine-episode Squid Game would ultimately become 2021’s second-most-streamed title in the U.S. across all platforms behind broadcast transplant Lucifer, which had 84 more episodes to boost its consumption tally (a difference that amounted to 16.4 billion versus 18.3 billion minutes viewed).

That runaway overachievement put Hwang and his cast on the awards campaign trail for a full year, ultimately netting SAG honors for lead actor, lead actress and the stunt team; a Golden Globe for supporting actor; and six Emmys (out of 14 nominations), including the big prizes for directing and lead actor.

“There are certain [heightened] emotions that Koreans like to portray onscreen, and I think the [rest of] the world initially found our stories unique,” says Lee, who became the first Asian to win a leading actor Emmy. “But they realized they could relate and they began to put themselves in the shoes of the characters.”

By all accounts, extending the series was a no-brainer. “I don’t know if it was me or Netflix that said it first,” says Hwang. “Everything just came very naturally. Because [all the fans] I met at the time thought there was definitely going to be a season two, I also got to thinking, ‘OK, we are going to do a second season.’ ”

Bajaria says that the knowledge that the second season will be consumed by a worldwide fan base did not affect its development: “If you try to make a show for everyone, you make it for no one. The conversation we had was, ‘Let’s not get tripped up by the global audience and try to make it broader because it’s for more people.’ And director Hwang was never going to try to make it something it wasn’t. He took the time to make sure he had a story he wanted to tell, and when he was ready for that, that’s when we did it.”

Squid Game’s original characters and set pieces had been more than a decade in the making, adapted from an unproduced feature screenplay that Hwang wrote in 2009. But given that most of the first season’s ensemble would not be returning (because their characters did not survive the titular contest), the filmmaker had to “start from scratch” for the next installment.

Season two picks up exactly where the first left off. Gi-hun, the sole survivor and winner of the game’s latest edition, is about to board a plane to see his estranged daughter in America when he has a last-minute change of heart, unable to settle his conscience as long as the sadistic competition continues to take place. “I was thinking about Gi-hun’s unfinished quest,” says Hwang, “and about the Matrix where Neo is given the option of the blue or red pill. He could have just lived happily on, but he chooses to take the pill where he becomes aware of the Matrix and struggles to get away from it.”

Lee — who also starred in Disney+’s The Acolyte this summer — notes that he spent a lot of time with Hwang modulating the character’s evolution from idealistic, somewhat naive underachiever to grim man on a mission. “Sometimes [Hwang] would say that’s too much or not enough of ‘Season One Gi-hun’ when we shot different scenes. I think a lot of people are expecting him to be [more hardened or cynical], but that’s exactly what we’ve been deliberating as we film,” he says, noting that season two gets even darker than the first, making it rarer for Gi-hun to express his innate “goodness of heart.”

Other than Gi-hun, the only other returning characters are Front Man (Lee Byung-hun), the game’s mysterious operator; Jun-ho (Wi Ha-joon), the police detective who learned last season that the missing brother he’s been searching for is none other than Front Man; and the Recruiter (Gong Yoo), the charismatic, well-dressed man who solicits prospective players with a simple wager that tests how willing they are to debase themselves for money.

“There weren’t many characters who survived, so I did kind of expect [Hwang] to ask me back,” laughs Lee Byung-hun, the global crossover star (Terminator Genisys, G.I. Joe, The Magnificent Seven) whose reveal as the face behind Front Man’s mask was initially simply an Easter egg cameo. “After the show was released, I would bump into him in places like press conferences and he would talk to me about a possible season two and different ways it could go. In season one, you only saw pieces of this guy’s story. There was a lot of freedom to build this character.”

Of course, success means that creative freedom now comes with a considerable degree of pressure. “I have about two nightmares a week, usually about something going wrong during shooting or people saying that it’s not good,” says Hwang, sitting in a rehearsal room in Studio Cube at the end of yet another day of filming. “Will the games be as entertaining as in season one? Are the characters as charming?”

Not that Hwang — who already lost multiple teeth amid the stress of making that first season — would have it any other way. He is wearing a black baseball cap with a curious phrase on it: COMFORT ZONE WILL KILL YOU. “This is kind of my slogan,” he explains. “Whenever I work on a project, I have to go the route that scares me because it motivates me so much more. It equips me with the drive to overcome that fear.

“Season two of Squid Game is probably the project that gives me the most anxiety,” he continues. “Seeing it from that angle, it’s going to be either my biggest success ever or the biggest failure.”

***

Hwang Dong-hyuk’s inspiration for Squid Game was personal; its conception took place during a particularly impoverished period in his career, when financing for a film project fell apart and he found himself broke in his late 30s, passing time in comic book cafes reading manga about battle royales and daydreaming about such competitions being his own ticket to financial salvation.

But his preoccupation with economic inequality took root much earlier than that. After his father, a journalist, died of stomach cancer when Hwang was 5, the future filmmaker watched his mother take on multiple odd jobs in order to support him, his brother and his grandmother. “Despite all of her hard work, we lived very poor for a very long time,” says the Seoul native, now 53.

Fortunately for the household, the young Hwang demonstrated great scholastic aptitude. “As long as I can remember, I was the hope of the family. Because I was a good student, my mother expected me to go to a great college, get a great job, make a lot of money and carry our family up from the bottom,” he continues. “That was my only goal in life.” (This was the backstory of season one’s Sang-woo, Gi-hun’s childhood friend and the golden boy of their working-class neighborhood, whose failed investments forced him to join the game.)

Hwang was accepted to Seoul National University, one of Korea’s most prestigious schools, but says that “when I enrolled in college, that’s when I began to think, ‘Why did I live my entire life only thinking about that goal?’ I became less interested in getting a good job and making money and more interested in why the world was divided so drastically between the haves and the have-nots. Why is it that, despite my mother working so many long hours at so many different jobs, we still have to live like this?”

Hwang’s epiphany led him to join leftist student movements in college and study film. He moved to the U.S. in 2000 to attend USC film school, where his thesis short — about a Korean woman searching for a brother who was adopted in the U.S. as a young boy — won a DGA Student Award and a Student Emmy. After receiving his MFA, Hwang remained in Los Angeles for two more years (working for, incidentally, a company that adapts foreign content for local audiences through providing subtitles, dubbing and other services). Living as an expatriate for six years, the young director was struck by the socioeconomic stratification, as well as how especially stark the class and racial divide appeared to be in this country.

“If I went near the wealthier areas, everything was just so pristine, the houses were nice, and it was usually white-dominant neighborhoods,” he recalls. “But where my school was, you would see a lot of unhoused people, there were a lot of robberies, and the population was mostly nonwhite. While obviously we have the wealth gap in Korea, we don’t have racial diversity. In L.A., there was almost this huge invisible fence between these different populations.”

It was also a time to further dismantle illusions about himself, and about the wider world. “In Korea, I went to one of the best schools in the country, and everywhere I went, I was treated as one of the elites,” he says of his college years, whereas being an international student in the U.S., “I learned that the world is indeed a huge place and I am just a speck floating by.” Riding the Metro to the Beach Cities one day, he stared at the view of South L.A. outside his window. “I still vividly remember looking down from the train above,” he says. “People talk about the American dream and its prosperity, but I was thinking, ‘Maybe this is what the real America looks like.’ ”

After returning to Korea, Hwang found success with his second feature, 2011’s Silenced, which was based on the true story of systemic sexual assault by faculty members at a school for deaf children. The case received little media attention and the perpetrators faced few consequences when the investigation first broke in 2005, but Hwang’s film, which topped the Korean box office for three straight weeks, provoked public outrage to the extent that the National Assembly eventually passed a bill, dubbed the Dogani Law after the movie’s Korean title, abolishing the statute of limitations and increasing penalties for sex crimes against minors and people with disabilities.

Some may consider the legislative and social impact of that film an ideal fulfillment of Hwang’s goals as a filmmaker, but the director notes he doesn’t necessarily have such didactic aims. “I don’t want to say, ‘This is what you should be thinking after you watch the series.’ I don’t think that would be meaningful,” he says. “It would be so much more organic for viewers to watch and then maybe come up with their own questions.”

He is similarly unbothered by the irony that the greatest outcome of Squid Game’s success may be commercial — the first season generated reportedly near $900 million in “impact value” for Netflix, which has so far spun off the IP into an unscripted competition series, live experiences in three cities worldwide and, coming soon, a video game. “I get this question a lot: Do you think it being created into a reality show overshadows the message?” says Hwang, who signed over Squid Game’s IP rights in his original Netflix contract. “But as content creators in a capitalist society, at the end of the day, everything we put out there is a product. The first objective for me is to create something entertaining for the viewers and commercially successful for me and for the investors. Squid Game is not something that was made with government money to educate the public.

“But having said that, as a creator, I always want the product I create to carry value. I would love for it to give you food for thought, to help you ask questions,” he adds. “This series holds in it every emotion I think I’ve ever felt in terms of the way I view human beings and the world, all the elements of tragedy and comedy throughout life. It’s all in there.”

The worldwide mainstreaming of Korean popular culture known as Hallyu had already been underway for years before Squid Game made its bow, but in reaching the apex of its respective medium, the series has joined Parasite and BTS as the holy trinity of just how high and how far the nation’s cultural exports could travel. In Hollywood, even as domestic production of scripted series declines (down 14 percent from 2022 to 2023), U.S.-based streamers continue to invest in original content from Korea in an attempt to catch up to Netflix, which has committed to spending $2.5 billion over four years on film and TV production in the country.

“Squid Game changed where people always expect big [shows] to come from,” Bajaria says. “It was the biggest, loudest [proof] that great stories can come from anywhere and be loved everywhere.”

Of course, the show has benefitted from its share of the bounty, with a “so much greater” production budget than the first season’s reported $2.4 million an episode. “In season one, there were cases where we had to tweak the idea because of budget limitations,” Hwang says. “This time, I was able to fully realize my creative vision, whether it was the set building or CGI. We didn’t have to compromise.”

But the creator adds that the biggest advantage of the show’s success has been in casting. Lee Jung-jae and cameos from fellow top Asian stars Lee Byung-hun and Gong Yoo notwithstanding, Hwang says he had trouble recruiting A-list talent for season one because of its platform’s relative lack of local popularity at the time. “Because Netflix wasn’t as established in Korea, there were actually some actors who said, ‘I don’t want to do it because it’s a Netflix show,’ ” he says. “After season one, we saw the cast becoming huge global stars overnight. Thanks to that, I was 1731432092 able to cast the exact actor that I wanted for every role.”

The new ensemble includes a deep bench of established drama favorites as well as pop stars whose personal followings will likely further expand Squid Game’s fan base. “There are so many veteran actors in season two, so I was very nervous in the beginning, but they all made me feel at home,” says Jo Yu-ri, a member of popular former girl group Iz*One who landed her role on the show after four rounds of auditions. Jo plays a young woman who is surprised to discover her ex-boyfriend (played by actor-singer Yim Si-wan), a crypto bro, has also joined the game, and their storyline is emblematic of new storytelling aspects that Hwang wanted to explore.

“We didn’t have that many young people in the game in season one because when I was first working on the script, there weren’t reasons for the younger generation to be so hugely indebted,” the writer explains. “However, during the pandemic, there was this huge cryptocurrency craze that led to so many young people getting neck deep in debt and driven into poverty.”

Jo and Yim’s characters aren’t the only ones with preexisting relationships who, unbeknownst to one another, have both been recruited into the game. “Those that created the games intentionally put them there to give more entertainment factor to those that are watching,” teases Hwang.

The clash between Gi-hun and Front Man — who also is a past winner of the game — will drive the remainder of the series, which will conclude with a third season in 2025. It’s a conflict that raises questions about what motivates people to dehumanize others, whether for sport or profit, and if this inclination can be overcome. “One word that was top of mind for me while shooting season two was ‘conscience,’ ” offers Lee Jung-jae. “It’s not something that’s absolute, but to call ourselves human, we have to be true to our conscience, and when we are not, we have to be able to feel shame.”

This story appeared in the Nov. 13 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Source: Hollywoodreporter

Related Posts

- Roundball Rocked: With NBA Return Looming, NBC Purges Scripted Roster

- SoundCloud Says It “Has Never Used Artist Content to Train AI Models” After Backlash on Terms of Service Change

- Fox News’ Camryn Kinsey Is “Doing Well” After Fainting on Live TV

- Kerry Washington and Jahleel Kamera in 'Shadow Force.'

Courtesy of Lionsgate

…

- This Alternative Artist Landed a Top-20 Chart Debut With an Album Made Almost Entirely on His Phone