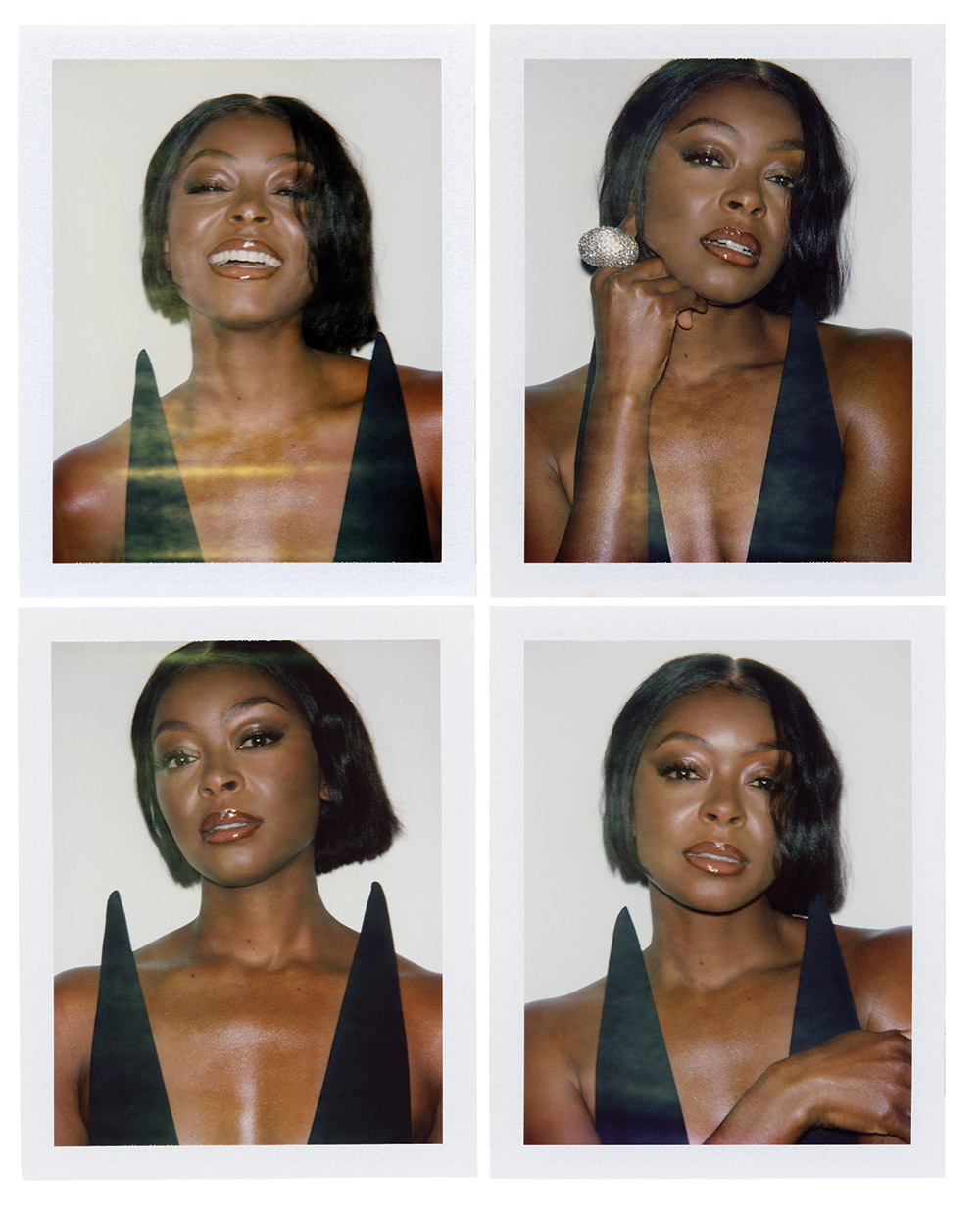

Danielle Deadwyler Struck All the Right Notes With Denzel’s ‘The Piano Lesson’ (and She Won’t Be Snubbed Again)

On a bright, late summer day in midtown Manhattan, the city’s bustling sidewalk traffic has been brought to a standstill. Clutching morning coffees, a small gaggle of curious onlookers have gathered on a Fifth Avenue corner to watch Danielle Deadwyler pose for a photographer who can’t get enough of the gamine star’s enviable beauty. It helps that Deadwyler, sporting a perilously low-plunging Sportmax sheath dress and demure white patent leather pumps, is putting on quite the show, serving a range of looks — from coquettish to fierce — in rapid-fire succession. “Is she famous,” a tourist, thrilled to be enjoying a New York moment, asks. “Should I know her?”

The answer is a definitive yes. Though not yet a household name, Deadwyler has been delivering the type of performances that garner rapturous praise from critics, co-stars and fans alike. An actor’s actor, she shined as the tortured graphic novelist in HBO Max’s dystopian drama Station Eleven and stole scene after scene in Netflix’s star-studded Western The Harder They Fall, playing Cuffee, a butch saloon bouncer whose sharp tongue is as lethal as her ever-present pistol. Her tour de force performance in Till should’ve earned her an Oscar nomination last year, but, shockingly, Deadwyler was denied a nod. The film’s director, Chinonye Chukwu, blasted the Academy for its failure to acknowledge Till in any major categories. “We live in a world and work in industries that are so aggressively committed to upholding whiteness and perpetuating an unabashed misogyny towards Black women,” she wrote in a viral Instagram post. Deadwyler supported Chukwu’s protest and yet admits she’d always been reluctant to invest in any Oscar chatter. “I know what that organization has done in the past and how [Black-helmed projects] have been received,” she says. “I wasn’t setting myself up for fooling.”

Deadwyler’s latest film, The Piano Lesson, playing at the Toronto Film Festival on Sept. 10, is an update of the Pulitzer Prize-winning August Wilson play first staged in 1987, and should prove impossible for the Academy to ignore. Set in Pittsburgh during the aftermath of the Great Depression, the story revolves around a pair of siblings battling over the titular piano, a prized family heirloom adorned with hand-carved images of their ancestors. Deadwyler delivers an incandescent performance, fully inhabiting the character of Berniece, a striving single mother in mourning who has a complicated relationship with the storied upright. It’s an albatross that simultaneously chains her to the past and blocks her brother, Boy Willie, played with a crackling intensity by John David Washington, from his dreams of a liberated, land-rich future. Samuel L. Jackson, Corey Hawkins, Ray Fisher and Michael Potts round out the cast. (A recent Broadway revival of The Piano Lesson, directed by Jackson’s wife, LaTanya Richardson Jackson, won raves before ending its run in early 2023.)

The movie marks Malcolm Washington’s directorial debut (his father, Denzel Washington, is an executive producer on the film, and it’s the third of Wilson’s plays that he’s ushered to the screen). At only 33, the most junior of the accomplished Washington clan offers a work so assured, it will easily discount any potential nepo baby aspersions. The opportunity to join a troupe of pedigreed all-stars was a definite draw for Deadwyler, but the young director’s vision for the film is what ultimately persuaded her to sign on, she says. The two closely collaborated in the shaping of Berniece, who, in this current incarnation, was inspired by the life and works of celebrated author Zora Neale Hurston. They spoke at length about Berniece’s agency in the world, who she may have been without the twin specters of racism and misogyny hindering her, and who she could still be despite those near-insurmountable obstacles.

“I’ve been waiting to shout on a mountaintop about Danielle Deadwyler, and people are starting to let me do that and I’m so excited,” Malcolm Washington says. “Danielle could call me to direct her niece’s sixth birthday party, and I would gladly do it. She’s a great creative partner, and we have such a wonderful collaboration. I hope it is one that we get to live out for the rest of our lives.” The feeling is mutual, the actress says: “I’ll work with him any day, any time, any hour, let’s go!” Adds John David: “She holds so much power in her silence, she commands the screen when she speaks. Her artistry is the gravitational pull of the August Wilson ecosystem in this film.”

Deadwyler has just finished her photo shoot and trades the glam frocks for a decidedly understated denim button-down shirt, flared athleisure pants and a jaunty leather bucket hat. She looks significantly younger than her 42 years, a fact that did her no favors during her brief stint as an elementary school teacher in her native Atlanta. She often was mistaken for one of her students and, today, could still easily pass for a teenager. Spend a bit of time in her presence, however, and it quickly becomes clear that Deadwyler is no green ingenue.

Sportmax dress, Isabel Marant jewelry. Photographed by Emma Anderson

A graduate of both Spelman College and Columbia University (she holds a history degree from the former, a master’s degree in American studies from the latter, and an MFA in creative writing from Ashland University), she speaks like the academic that she is. As a result, her answers to my queries rarely arrive in easily digestible sound bites. At times they’re long and professorial, other times opaque and tangential. Nevertheless, this cerebral actress is game to discuss anything during our lunch at an Italian bistro popular with the corporate card-wielding set, so we tuck into Tuscan salmon salads and delve into politics.

What does she make of the fervor around Kamala Harris’ historic presidential bid? “It’s fascinating and fabulous for a Black South Asian woman to be running,” she says. “America has a tendency to feel lighthearted once a first is in occurrence, but it means nothing if there’s no second, third, fourth or fifth. I’m not interested in being pessimistic, but naivete about American history is not a good thing.”

Deadwyler’s superpower? An uncanny ability to speak volumes without uttering a single word. The New York Times once described her eyes as “an instrument that she can play with precise control.” If her eyes are indeed an instrument, then her face — with its Olympian gymnast-level elasticity — is an entire philharmonic orchestra. She can make an upturned mouth spell doom; a downcast side-eye, rage; a furrowed brow ripple with delight or righteous indignation. “She’s in such control of her body, the way that she moves through space, the way that she can make space move around her with her face, her eyes, her physicality,” Malcolm Washington marvels. “She’s a rare performer who has the full tool set.”

That was evident during a harrowing supernatural scene in Piano, in which Deadwyler’s eyes roll so far into the recesses of her cranium that you’re left feeling both deeply unsettled by the visual spectacle and in awe of her astounding talent. “That moment was so wonderful because she went to some other place that was just profound,” Washington says. “I remember looking at the monitor and not even wanting to cut. We just kept rolling because I wanted to see what she would surprise us with next.”

Said scene no doubt should deliver Deadwyler much-deserved awards consideration, but she’s not in this game for the golden hardware, she states definitively. “This movie is about Black family healing. It’s about our divine connectivity to the beyond, to our ancestors, to our children,” she says. “Why would I give a damn about a conversation about awards being had over the conversation that should be had about our healing? That’s realer to me.”

The Harder They Fall Netflix/Courtesy Everett Collection

She points to the racist propaganda of the 1915 film Birth of a Nation and the catastrophic power it had in shaping stereotypical perceptions of the Black race. If film can cause that level of devastation, surely it can uplift a people as well, she reasons, with a touch of poetry: “Our works should bolster our love of self, our awareness of history and be a ravine for our care and consideration.”

On and off camera, Deadwyler is dead set on wrestling with this nation’s complicated past. When I point out that the entertainment industry appears to be perennially preoccupied with slavery period pieces — from Alex Haley’s Roots to Quentin Tarantino’s Django Unchained — she bristles. “That’s a lie, that’s a lie, that’s a lie,” she counters ruefully, shaking her head. In her estimation, we need more thoughtful explorations of this painful era in Black history, not fewer. “I’m not going to lie. It’s scary to engage, but you do not go anywhere unless you confront,” she says. “Therapy has taught me that.”

In addition to therapy, the actress is deeply committed to a health practice that includes everything from meditation to regular acupuncture treatments. After wrapping her most recent project, The Woman in the Yard, a horror thriller from Blumhouse and Universal Pictures, she took several months off to recover. “As much as I put into labor for my personal artistic pursuits and professional pursuits, I put into my wellness,” she says, adding that she spent the summer happily vacationing with her 14-year-old son. “I love being with him,” she says, beaming. “He’s smart and beautiful and kind, and we have a super honest relationship.”

Given the tear-inducing nature of much of her oeuvre, one would be forgiven for thinking Deadwyler would be, well, intense. “Everybody after Till, was like, ‘Are you OK, sis?’ Yeah, I’m good!” She laughs easily and, in the right company, can be downright silly. If you’re ever in need of a quick pick-me-up, google her impersonation of The Lord of the Rings’ Gollum, rapping Sir Mix-a-Lot’s classic ode to outsized posteriors, “Baby Got Back.” When jokes would fly between takes on the set of Piano, Deadwyler more than held her own in the company of the nearly all-male cast, Washington recalls. “Danielle is one of the funniest people in the world,” the director says. “Danielle will have you keeling over.” Adds Deadwyler, “Laughter, humor, the absurd, the surreal — all of that plays a part in my life.”

Till Lynsey Weatherspoon/United Artists Releasing/Courtesy Everett Collection

Born and raised in southwest Atlanta, Deadwyler, the daughter of a legal secretary and a railroad supervisor, has been performing since she was a toddler. Her mother first spotted her latent talent while watching her baby girl shake it down during episodes of the seminal music show Soul Train and enrolled her in dance lessons. Theater classes soon followed. Working for the collective good of the community also was instilled in her during those formative years. She and her siblings were all required to volunteer for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the venerable civil rights organization founded by Martin Luther King Jr. in Atlanta during the late 1950s. She discovered Wilson’s groundbreaking catalog in her teens and dove deep into the playwright’s American Century Cycle series, comprising 10 plays that capture the Black experience in Pittsburgh throughout the 20th century.

Still, life as a professional actor was unfathomable to Deadwyler, given her family’s blue-collar roots. “My grandparents were sharecroppers,” she says. “My maternal grandparents worked in a poultry factory for more than 30 years of their lives.” After her older sister — the first in the family to graduate from college — pursued her dreams of being a screenwriter, Deadwyler realized a career in the arts was indeed possible. She recalls thinking at the time: “Even if I don’t know where it’s going to go, it didn’t matter. I had to do this thing that I’ve always known.”

It occurs to me that Deadwyler’s own biography — driven Southern dreamer defying convention and chasing a self-determined future — could easily be the spine of a Wilson play, which may explain why his canon has so deeply resonated with her. “August Wilson’s works are quintessentially Black life in America — the Wilson Century Cycle is a wide-eyed entryway into the American family experience … to global human pursuits, self-determined life, connectivity to land and the hand of Spirit on our efforts,” she says. “August left us stories, truths to enhance and to challenge our own becoming. I am challenged to refine my becoming every time I read, witness and feel his work.”

Deadwyler has worked steadily since landing an ensemble part in a 2010 Tyler Perry-directed Lionsgate production of For Colored Girls, based on Ntozake Shange’s 1976 longform poem For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf. Deadwyler by now has amassed a body of work that includes self-helmed experimental projects as well as more commercial fare. One might know her as the easy-to-anger LaQuita in Perry’s The Haves and Have Nots that aired on OWN; the brassy bartender Yoli in the cult hit P-Valley; a profane, champagne-swilling partygoer decimating interracial relationships on FX’s Atlanta; or as Zola, the selfless stalwart nursing her kid sister through heartbreak in Netflix’s From Scratch. We’ll see even more of her in the coming months. The Woman in the Yard arrives in theaters early next year and she reteams with Netflix for Carry On, an action-packed thriller made for “popcorn and Christmas spirits,” says the actress, who plays an FBI agent. She again proves that she’s built for battle in 40 Acres, a postapocalyptic thriller premiering at TIFF on Sept. 6 that centers a family of farmers fighting to save their land from cannibals.

40 Acres, an indie thriller premiering at TIFF. Courtesy of TIFF

Washington predicts that Deadwyler will have a long and storied career. “She has great taste,” he says, “and she’s so considerate about what she puts her energy and time into.” Deadwyler is more than ready to go the distance. “I’ve learned that a sedentary life leads to death,” she declares. “So let’s keep moving.”

This story first appeared in the Sept. 4 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Source: Hollywoodreporter

Related Posts

- Roundball Rocked: With NBA Return Looming, NBC Purges Scripted Roster

- SoundCloud Says It “Has Never Used Artist Content to Train AI Models” After Backlash on Terms of Service Change

- Fox News’ Camryn Kinsey Is “Doing Well” After Fainting on Live TV

- Kerry Washington and Jahleel Kamera in 'Shadow Force.'

Courtesy of Lionsgate

…

- This Alternative Artist Landed a Top-20 Chart Debut With an Album Made Almost Entirely on His Phone