How Spielberg, Coppola and Lucas Rewrote Hollywood’s Rules in 1970s

The 1970s were a golden age of American cinema. Most movie buffs are familiar with an agreed narrative of how the decade happened: a new young generation of filmmakers, whose names became the stuff of legend — Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, Francis Coppola, William Friedkin, Martin Scorsese, Mike Nichols, Brian De Palma, Terrence Malick — arrive on the scene, overtaking the old, crusty studio system. They invent the blockbuster, make movies more violent and sexy than any mainstream films had been before, and generally run wild, their egos out of control, until a string of self-indulgent productions, most infamously Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate and Francis Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, lead studio executives to reassert control. In this narrative, they are the sex and drugs generation, a group of talented lunatics taking over the asylum.

I went to film school in the early 2000s and I was consumed with these filmmakers, who had made the films we all loved so much: The Godfather, The Exorcist, Star Wars, Jaws, Taxi Driver, The Graduate, Badlands. Even then, though, the popular take — the story of the lunatics taking over asylum — didn’t sit right with me. It felt like cultural history the way studio executives wanted it written: filmmakers might make great films, but they’re mad people. They need us, the responsible adults, to guide them.

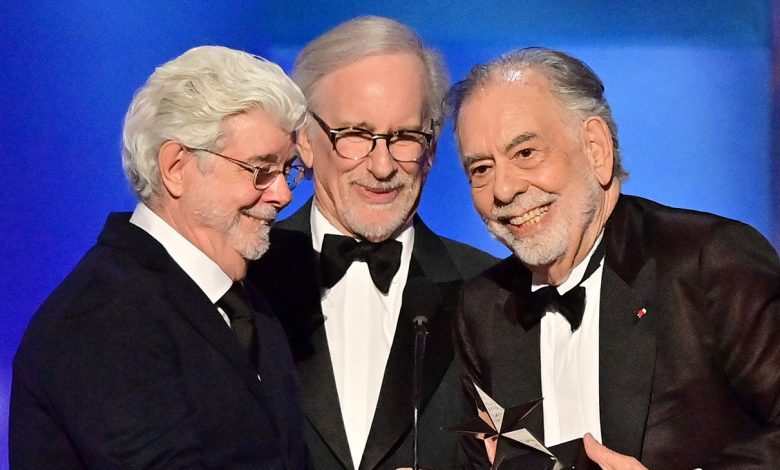

As I learned about the decade, a more truthful, more interesting story revealed itself. It started in 1967, when a young, successful screenwriter named Francis Coppola met an even younger film school graduate named George Lucas. They and their peers had lost faith in corporate capitalism. The world seemed hopeless around them: America mired in bloody foreign wars, corruption in the White House, mainstream entertainment tired and repetitive, controlled by conglomerates growing bigger and more faceless every day. Coppola and Lucas were, in many ways, kindred spirits. They wanted to make great films, but they also wanted to control those films and profit from them. They wanted not to need studio executives. Within a year, they leased a warehouse in San Francisco and left Hollywood to start a hippy collective of filmmakers; within the same time period, they met and befriended another young man, Steven Spielberg, who also craved creative freedom but wanted it within the studios.

They took on the system — and they won. Back-to-back, they made the biggest hits ever: Coppola with The Godfather, Spielberg with Jaws, Lucas with Star Wars, Spielberg again with E.T. By the early 1980s, both Coppola and Lucas had their own studios. Spielberg was so successful that studios would greenlight anything he wanted. Many of their peers sought to emulate them. Then a new generation of studio executives came in. Not to re-establish order over unruly creative children, but to co-opt their success. To copy their methods and turn them back into employees.

The Last Kings of Hollywood, by Paul Fischer.

Celadon Press

That’s the story of 1970s American cinema that I tell in The Last Kings of Hollywood. To write it, I interviewed hundreds of people, from filmmakers themselves to crew members, family members and studio employees. I went back to original contemporaneous sources. I focused on these men’s daily efforts to achieve creative autonomy. I tried to tell it as it happened. As the people who lived it experienced it.

There are filmmakers in Hollywood now, working under the same conditions — bloody conflict abroad, corruption in politics, monolithic mainstream entertainment — and striving for a similar freedom. Last year, Sean Baker, an independent filmmaker who had directed four films before his mainstream breakthrough and often shoots and edits his own work, won four Academy Awards for Anora, including Best Picture and Best Director, tying Walt Disney for the most Oscars won by a single person in the same year. This year, Ryan Coogler’s Sinners received the most Oscar nominations of any film in history, and it’s a film which reverts to his own personal ownership in twenty-five years, a deal not unheard-of and not unlike the deals Francis Coppola negotiated to retain ownership of some of his own work, yet decried by some Hollywood insiders who prefer certain filmmakers be unable to do so.

As I type this, the actor Kristen Stewart is promoting her first acclaimed movie as a director by decrying the industry as a “capitalist hell” from which filmmakers need to “start stealing” back their own movies. James Cameron, like George Lucas decades ago, self-finances his own franchise of technologically-groundbreaking blockbusters, and damn whoever tells him he should be doing something else. They, and hundreds of other American filmmakers, fight one of the legacies of Coppola, Lucas, and Spielberg: the tentpole blockbusters and “franchisable intellectual property,” like Star Wars and Indiana Jones, that have come to dominate all entertainment. Yet at the same time, they carry on another legacy, the one Coppola and Lucas fought for when they moved away from Hollywood and started a little production company in a leased warehouse in the sketchy part of San Francisco: that of popular filmmakers fighting to retain the autonomy of an artist.

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the movies section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.