James L. Brooks Is Back With a New Film and Already Has Notes on His Next One

It’s Sunday in New Orleans, and James L. Brooks has manners on the mind. The 84-year-old, who has maxed out his multihyphenate talents over the course of a legendary career that’s still firing on all cylinders six decades later, is in the Big Easy for reshoots on Ella McCay, the 20th Century Studios comedy that marks his return to the director’s chair after 15 years, and he’s thinking about how people respond to him in public.

“The thing about New Orleans is that when you make eye contact with somebody, that person is going to smile at you and say something pleasant,” he says with a grin of his own over Zoom. “That’s how the manners are here, and it’s amazing to be around. I’m going to try and make that happen in Los Angeles when I go home. I’ll let you know how the experiment works out.”

اRelated Posts:

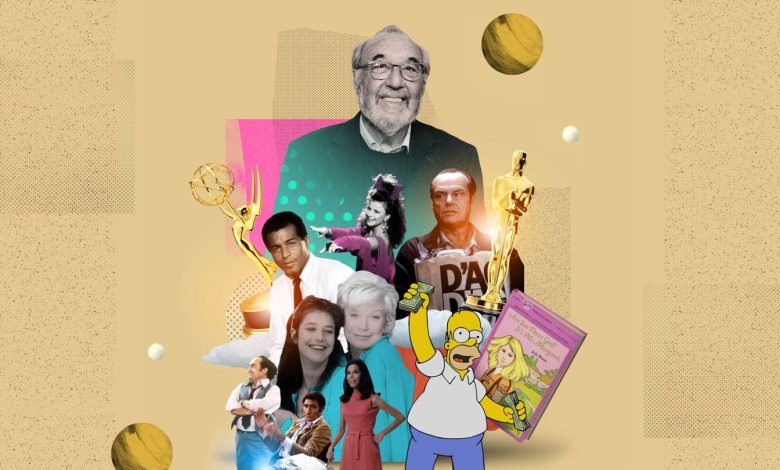

If personal experience is any indication, people — especially in Hollywood — will continue to be very nice to Jim Brooks, the man who made his debut as a TV writer on beloved shows (The Andy Griffith Show, My Three Sons) before creating wildly successful series like The Mary Tyler Moore Show (and the spinoffs Rhoda and Lou Grant) and Taxi. He went on to conquer the big screen with classics like Terms of Endearment (which won five Oscars), Broadcast News and As Good as It Gets … before changing TV history forever with The Simpsons, and being inducted into the TV Hall of Fame in 1997.

But if you happen to cross paths with the ever-humble Brooks, you might want to dial it back. After being asked about his good fortunes — an awards haul that includes three Oscars, a historic 22 Emmys, a Golden Globe and honors from the DGA, PGA and WGA — Brooks jokingly says “stop it” to this reporter when reminded that his shelf will soon be more crowded when he receives a Cinema Verité prize during CinemaCon in Las Vegas in early April.

During an hourlong conversation, Brooks opens up about the magic of trusted collaborators like Albert Brooks and Jack Nicholson, that time he was banned from the set of one of his films and why it’s always about the talent on set: “My favorite thing is making the shoot all about the actors as much as possible.”

Ella McCay is your first movie since 2010. The easy question is why?

I produced three other films in that time [Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret; Icebox; The Edge of Seventeen], and when I produce, I’m on the set all day, every day. I always think that when you’re directing, you get a distorted reality and you lose touch with the world. The movie is entitled to that, and you don’t want to feel crazy for feeling that way. When you produce for someone else, you want to feel the way that they do.

What did it feel like to get back in the director’s chair?

My favorite thing is making the shoot all about the actors as much as possible, so for me it felt good to be able to try and do that.

Let’s talk about those actors. You assembled quite a cast …

There are several people I have worked with before, so for continuity, that feels really good. Then there’s Jamie Lee Curtis, whose spirit permeates and is infectious in a great way. She brings a humanity, moment to moment. When the making of a picture can become snarky, Jamie is just a wall against that. Also, it helps that she has the best hug in town.

Jamie Lee Curtis and James L. Brooks on set on 20th Century Studios’ Ella McCay. Photo by Claire Folger. © 2025 20th Century Studios

I’ve lucky to know her and I can confirm that hug. I know you’ve been writing the script for a very long time. When did you first start putting words on the page?

Thank God I don’t know the answer to that. To know would be embarrassing. I have a day job that I love on The Simpsons, so there’s always that to focus on.

Are you still working long days on The Simpsons?

Not while I’m doing a movie, but I have input on every single episode. We have a great group working on it, and we have a great showrunner in Matt Selman. Even though I was filming, I was able to be there for readings on Zoom and stuff like that.

Matt Groening, director David Silverman and Brooks at the Springfield, Vermont, premiere of The Simpsons Movie in 2007. Scott Gries/Getty Images

Not much is known about Ella McCay beyond the logline …

What is the logline you have? It’s going to make me cringe …

“Ella McCay is about the complicated politics that arise when a young woman’s stressful career clashes with her chaotic family life.”

That’s OK.

How would you describe it?

My logline would take about 45 minutes. I came from a family that wasn’t roses and warm bread, and so I wanted it to be about one errant parent and getting over the loss of a parent. I never want to do anything that’s not a comedy, and I always want to represent life.

I found a clip of a press conference about shooting the movie in Rhode Island. Alongside government officials, Jamie Lee Curtis read a line from the script: “Government works best when citizens stay interested because if you don’t know what you want, you’ll probably get what someone else wants.” That line seems to represent life in 2025. How do you feel about the movie landing this year?

The film is set in 2008, before we had this enormous division. There’s a reason for that, and it’s because it’s not about that. The picture is about how to not make government service and political office something any sane person would flee from. In a movie like this, you’ve got to figure out what the heroism is, and chase that. What is it really that makes you a fine person? Is it a character that’s worth supporting for an entire movie? That’s what you aim for.

I have to ask you about Emma Mackey, who plays the title character. I have followed her since Sex Education. It was clear even from that series that she was destined to be a star.

It’s great to hear you say that, because I was aware of Sex Education. She brilliantly played a 16-year-old. She plays a range of ages in this movie, one of which is 16, and she’s remarkable. She was 28 when we started, and for the bulk of the movie, she plays 34. I was in an audition process for a long time. I went to London, and very late in the game she turned up, and that was it. In my mind, I pictured the kind of heroines that we had in the ’50s and ’60s, early Katharine Hepburn and Rosalind Russell. There’s a certain kind of great movie star we used to have, and Emma has a lot of those same qualities.

James L. Brooks (left) directs Emma Mackey and Woody Harrelson on the set of Ella McCay, which looks at the conflict between political work and personal lives. Claire Folger/20th Century Studios

Fans of yours will be happy to know that collaborators like Albert Brooks and Woody Harrelson are in Ella McCay. What was it like to get the gang back together?

Great. When you have the right spirit of the work, it’s so much easier. There’s a shorthand that comes with it. One of my favorite stories is about this stage play: They were going to open on Broadway, and the director called the cast over to deliver a crucial note. He said, “Do it better.” They all nodded and walked away knowing how to do that because they were such a tight-knit group. Television can be like that because of how it becomes like a family. But I’ve never had a movie experience as neat as this one.

Why?

I’ve worked with great people before, but you’re not supposed to have a great time. I’ll take a bad time for a good movie any day. But on this, there were never any silly distractions. It was always about what we were doing. We all came to work.

You’re doing reshoots now. You’ve long been the kind of person who is open to reshoots, edits, new directions and pivots during the creative process. Where did you get that?

Woody Allen used to schedule the reshoots before he started shooting, and I really understand it. You see the movie first and you have a preview. You’re nuts if that’s your final picture. It’s not cheap but I don’t know whether I’ve ever had a preview, especially a comedy, where you’re standing at the back of the theater and you didn’t want to change something. You can only get the feeling, that rhythm, once you’re there.

You did a fun interview with Criterion a few years back. You mentioned how Albert Brooks cast you in movies like Lost in America by promising you that you’d have fun but it never was. Why?

I was the actor from who would always be standing outside of his trailer the next morning begging, “Let me do the take again. I know I can do it better.”

Does that make you a better director when your actors come to you with similar requests?

Like I say, providing the environment for the actors where they can feel like they can do their best work is my job.

You’re heading to Las Vegas to CinemaCon to present Ella McCay …

I’m in denial of that, but yes, we’ll be there.

Why?

Getting up in front of a large group, let alone thousands of people in a theater, is not my strong suit. There’s a term that I didn’t come up with and I’ll never come up with, called a “sizzle reel.” That’s other people’s term. But we just cut one and we will be there and I’ve been thinking about what to say when I’m there.

You’ll also be getting an award, the Cinema Verité Award. As someone who has fortunately been honored with many trophies during your career, how do you feel about such acknowledgements?

It’s always a little surreal. I’m not exactly a comfortable public speaker, so there’s that element. Talking to you now, it’s taking on a reality that I haven’t allowed myself about it, so stop it.

Let’s go back to the beginning. You grew up in New Jersey and once said you had “an idea that you would end up selling women’s shoes for a career.” Why did you think that?

That is what I lived in fear of — that I would wind up on my knees all day, in a literal sense, as opposed to how it’s ended up.

You eventually made it to New York, where you worked as a CBS usher. How did you get that job?

It was a job that went to people who were college graduates, which I was not, but my sister’s best friend was the assistant to the man who hired them. So, it was an inside job. Literally, my ambition was to survive. I don’t think I’d be sitting here today if I didn’t get that job as an usher. Then I caught a big break because people like me, ushers, filled in as copy boys; they called us desk assistants in the news division. I got the chance to fill in for someone who was on a two-week vacation. The guy never came back, so that was my break. I never could have gotten that job otherwise.

What was your life like as an usher?

I lived in New Jersey and the job was in New York. Very often when I got off work, I’d walk to the bus terminal through the theater district at just the right time to catch the second act. Over the course of a season, I’d see just about every second act of every show on Broadway.

Sneaking in?

Yeah. By mixing in with the crowd. I never went to a huge hit. But you could always look for a stub on the ground or you’d find your way in somehow and go to the worst seats in the house. From there, you could usually see where the empty seats were and slip your way down.

As the story goes, it was your wife who gave you the courage to take a leap to working on documentaries?

Yes. My wife, who passed away not long ago and we were divorced before then, really wanted to go to California. We were really in love at that time and I had a job that was past my ambitions and dreams as a news writer. I loved the job, but she went to California. I followed her and it was tough to leave because I had a union job. But I found work doing documentaries, I think someone gave me some work half out of pity. Then I ended up getting a full-time job.

The titan of popular and cultural impact has also experienced career bumps. His first job was in documentaries, where he was laid off six weeks in, then brought back again. Aaron Rapoport/Corbis/Getty Images

I read that you got laid off six weeks later?

Yes, and they brought me back. He knew I was in tough shape so he gave me a chance to come in and do a job writing for National Geographic. I had a real phobia of insects — I’m not proud to say but it was a real phobia — and there I was poring over these huge blow-up shots of insects. It turned out to be therapy for my phobia and I got over it. It was a few weeks of shuddering.

I love what happened next. You went to a party with your documentary buddies and met a producer named Allan Burns, who had five shows on the air. You told him you wanted to write for television and he made it happen. You’ve called him “one of the greatest human beings that I’ve ever met in my life.” What do you remember about that chance encounter?

That was Allan. He was an open-hearted guy, day in and day out, probably all his life. Just think of how incredible that is. By the way, I went to that party with a rough little documentary group. We looked like some French underground band, and Allan was coming from an elegant affair wearing a tuxedo. We were all these grimy guys surrounding him. I told him what I wanted to do, and he got me an assignment to do a rewrite on a show that he had created. He didn’t even ask to read anything first.

Why do you think he took a chance on you?

There are very good people in the world.

What show was the rewrite for?

My Mother the Car. It was a series that ran two seasons, and you’re not going to believe that the premise centered on a car that talked. A man’s mother came back as a car. I’m blushing as I tell you.

We’ve lived through some talking cars in Hollywood. It’s a genre that doesn’t exist as much as it used to, outside of animation.

A talking horse is OK, and better than talking inanimate objects.

Reese Witherspoon and Paul Rudd in 2010’s How Do You Know. Columbia Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

You went on to write for The Andy Griffith Show, My Three Sons and The Doris Day Show. Shortly after, you got a big break creating Room 222, which was only the second show to have a Black lead, and it addressed topical issues in primetime. Where did you get the guts?

It was a great baptismal for me. The pilot episode, which I wrote, focused on a teacher helping a kid who was in trouble. I did a lot of research for that episode, and I had written it as him helping a Black kid, but the network at the time wanted the kid to be white. It got really serious, but Gene Reynolds, the producer and director of the show, never wavered. Of course, I had no pull at all.

It wouldn’t be the last time in your career that you came up against notes or fights with executives. What did you learn from watching Gene fight back?

It’s not just about resisting notes because the big rule is that a great note can come from anywhere. You can be immersed in a project and someone can mumble something and it can be a good mumble that you appreciate. The notes only come when someone involved cares about the work a little bit. I mean, it’s not a dictatorial process. A good note is a good note and you can get them all sorts of ways.

The show was produced by 20th Century Fox Television. It’s remarkable that it was your first creator credit, and years later you’re still in business with Fox.

They almost folded during those days, remember? They were on life support as a network. I think Barry Diller was in charge at that time, and it was something of an outlaw network. They had to try things to make it work, so it was a terrific environment. They also were less subject to network censorship than the other places at the time.

Room 222 lasted more than 100 episodes. What was the biggest lesson you learned on your first hit out of the gate?

Gene was so gifted, and he was a justifiably self-confident producer and director. He heard a good note from anywhere and he was ferocious in his devotion to the show. It was a great upbringing for me and it helped me raise my sights, raise my spirit and raise my horizon for what was possible.

You did not rest on your laurels. After creating a hit show, you moved on to The Mary Tyler Moore Show. I read how it was initially unpopular at CBS and they wanted to fire you. Grant Tinker, whom you’ve called “one of the best bosses,” demanded they keep you. How difficult was that for you?

It’s going to be hard for you to believe this, but we went in to present to Fred Silverman, the legendary guy in charge of programming at the time. I think there were 15 executives in a semicircle with the three of us sitting across from them. We presented them with what the first iteration would be. It had Mary being divorced. We went in there with a bad idea, not knowing it was a bad idea. We had Rhoda Morgenstern in it at the time, too, and one guy said, “There are two things the American public doesn’t like: Jews and people with mustaches.” I had a mustache at the time, and I’m Jewish. (Laughs.)

How did you respond?

I was scared. I’d never been in a meeting like that before. I was scared and I just wanted a job. But Grant had us step out and he took care of it. It wasn’t until years later, after the show was on, that we found out what had happened in there.

You called Grant the best boss anyone could ever have. Why?

He supported writers like nobody’s business. Every time we did the show, we did it for an audience. He was always in the booth with us. He fought for us. He had other shows with MTM Enterprises, and there were a lot of good ones. It’s a great break when you get spoiled in that way by such a boss with that kind of community and someone with good intentions.

What was it like to work with Mary?

We always went to the stage for run-throughs, we did rewrites, and we asked the actors to do it differently and stuff like that. She absolutely did it and never exercised authority except for the final episode. The final episode had the group dissolving and everyone had goodbye speeches. She came to our office — it was the first time in seven years — and said, “You don’t have me saying goodbye.” It turned out to be, of course, the best moment of the show.

Were the spinoffs Rhoda and Lou Grant your ideas or the network’s?

Rhoda [Valerie Harper] had been on the show for five years, and she wanted her own show, so we raised our hands. For Lou Grant, we loved the idea of, when a spinoff is not really a spinoff. When you spin off a comedy into a drama. That was fun. It became an hour show, so it was a whole different deal. It was filmed, and that, too, was a whole new experience and new education.

Speaking of new experiences, you turned your attention to something new with Taxi, which focused on the male blue-collar experience.

There was a magazine article about a taxi company, and they all had these Eugene O’Neill-like dreams about what would happen to them. I believe in a lot of research, but I’ll never have one day of research give me as much as I got by spending one day in a taxi company where the drivers kept coming in and out during a 12-hour shift. The hero of the piece happened because one guy came in and he was the one they were all waiting for, because he was the charismatic one. The same night, I saw the dispatcher step out of his cage and in front of us, one of the drivers gave him an under-the-counter payment. That gave us Louie De Palma, played by Danny DeVito. That’s one night when you get really lucky.

You’re not above spending weeks or months researching your work.

I’m lucky to do it. I won’t mention who it was, but for [Ella McCay], I was having breakfast with an ex-governor and the governor’s mate. The governor brought up something that had been a tough moment for them, and it became key to the movie. I knew it when I heard it. She had not mentioned him in a key speech that he was a part of, and he had political ambitions as well. It happened 15 years earlier, and it became clear during this breakfast that the upset was still there. As they went over it, she apologized again.

In addition to 1983 Oscar winner Terms of Endearment and 1997’s Oscar-nominated Broadcast News, Brooks also has directed Spanglish (pictured) with Adam Sandler and Téa Leoni. Columbia/Courtesy Everett Collection

You had so many successes in quick succession that it would be easy to talk about all of the hit shows that paved the way for films. But you had one show that was short-lived. What did you learn from The Associates and its cancellation?

First of all, thank God success was steam. The Associates was Marty Short right out of the box. Pure, innocent, out of the birth canal Marty Short. It was fantastic. We had fun. The pilot for that show really worked. You don’t get this very often, but the last line of the pilot delivered the most explosive laugh on the show. It was set up very carefully. We had a terrible dress rehearsal and the show was going long. We needed to fix some things and we fixed them. The last line hit and it was pretty special.

You’ve said in the past that the potential to have more authority over material led you to directing. Is that accurate?

I never had the ambition to be a director. Then somehow with Terms of Endearment, it evolved. It changed, and I truly have no idea when or where.

Maybe this will jog your memory. You wrote the script for Starting Over, and I read that the director, Alan Pakula, banned you from the set when you were visiting because you were visibly reacting to the actors. I wonder if that was your light-bulb moment?

I even worked in one naughty phone call to an actor, just because I was going crazy with the way this one line had happened. Pakula was great, by the way. I got to pick my director for that one, and that doesn’t happen very often. He was the standout guy. The reason he banned me from the set was because I was making all these faces, and he said, “Jim, when you’re directing, you don’t need to know everything. You need the illusion that you do.”

That’s great advice. Your creative output was and is so impressive. What’s your writing process? Are you an early morning writer?

Mornings, almost always. Things usually never look as good as they do to you in the morning shower. It’s the most optimistic time of the day.

You have also long given credit where credit’s due. You’ve thanked Debra Winger for bringing you Jack Nicholson for Terms of Endearment.

Jack, in a fantastic way, took care of me since it was my first film. He would come up to me at the end of the day and say, “Here’s the worst direction you gave today.” And then he would say, “Here’s the best direction you gave today.” He took all the tension out of it with his spirit.

It’s one of the great Oscar debuts of all time. Very few people, if any, have had their first film win as many Oscars as you did that night including best picture, best director, best screenplay and two Oscars for your actors. You’ve said it was an “orgasmic” night and that you felt like it was an out-of-body experience. Tell me more about that evening?

I remember precisely that. I remember at the end of the evening brushing the felt of the Oscar. I wasn’t able to form any words or anything like that. Jack won and Shirley [MacLaine] won and Debra was nominated but didn’t win. She did this great thing by posing in a picture with all of us holding our Oscars and she held her hands up to pose with an imaginary Oscar. It was the coolest thing ever.

You later talked about how fearful you were about how that level of success would impact your career. You thought it might deprive you of a certain anonymity because the spotlight would always be on you. How did you manage those feelings and make sure that you weren’t weighed down by that incredible success?

It was always a fearful thing. Success can be a demon. I had an awareness of it and after it happened, I went out and had this great year — maybe the best year. I asked this friend of mine — a hardened producer of many pictures — how many bombs I would be allowed after Terms of Endearment. He said, “I think you get two.” What I got was a ticket to freedom for at least a year. That’s how long it took to get over the experience and how disorienting it was. It allowed myself to poke around in different areas and experiment. That led to Broadcast News.

That proved to be an incredible follow-up, nominated for seven Oscars. Everyone says it’s an honor to be nominated, but you went home empty-handed that night. How did it feel to lose?

The truth is, I was OK. I was coming off the other experience. I was snarky. It’s not like I was smiling in the car, but I was being a little shitty just in the privacy of my own car to myself.

Tracey Ullman in The Tracey Ullman Show. R. Robinson/20th Century Fox Film Corp./Courtesy Everett Collection

Holly Hunter was a last-minute choice for the female lead, and I read that casting director Juliet Taylor brought her in as one more actor you should see in New York.

That’s how humbling making movies can be. If I had made the movie with the one actress who was in the running before Holly, it wouldn’t have been the movie. That’s it. You can’t live like that all the time because you’ll make yourself crazy. There are so many things in making the movie that could be the shoe that comes off. In Starting Over, the best speech I thought that I had ever written in my life up to that point was ruined because the trench coat that the actor was wearing was so new that when the girl beat on it, it was so loud. I went crazy. But it was a great lesson to go crazy over that. You do owe it to the movie sometimes for the craziness to exist.

Do you have an experience in your career when you went the most crazy?

On Broadcast News, I was trying a new ending, which was going to be that the movie ends with the girl driving away for the rest of her life and the romance is over. I wanted to do something like one of the French films and it would be so good. There would be tension. Right before [William Hurt] goes to get in the car, someone on the crew said, “Hi, Bill.” Holly heard him and I think that was the most out-of-body moment I’ve ever had. It made me think of the expression that Bill Hurt gave me once when he said, “We’re all crew.” It’s a good thing to say to yourself every once in a while. We’re all crew.

It seems unreal to say that one year after Broadcast News, and a year after producing the beloved film Big starring Tom Hanks, you found your way to The Simpsons, which changed television history. What is the key to the success?

Matt Selman, the current showrunner, is the antithesis of, “If it works, don’t break it,” thankfully. That’s led to what we all feel is a renaissance. You can feel it. We’ve used the fact that we have an audience to try new things, to mess around.

But you’ve been careful and thoughtful about not overdoing it. There’s not a universe of spinoffs or movies or an overdone expansion. Was that a decision from the beginning? Or have there been fights over the years about blowing it out?

It’s surprising how many of us are still around and have been since the beginning. Matt Groening, in particular. There’s always been a succession of showrunners, and that impacts the show. Matt and I are constants and we’re always there in some way or another. Matt Selman, this is his time, and he’s making great use of the fact that we can do new things, which is exactly what we’re doing and it feels good.

People say you can learn just as much through success as you can failure or challenges. I know you and Matt had a public feud about 30 years ago and it played out in the press. You managed to get past it. What did you learn from that impasse with a collaborator and how you buried the hatchet?

We’re all crew.

You went on to work with Jack Nicholson several more times after Terms of Endearment. What made your collaborations work so well?

On As Good as It Gets, if I didn’t get Jack for that, I hope that I would’ve been smart enough not to make the movie. He was the only man alive who could get an audience to sit and watch it and be interested because of who that character was. Boy, sometimes you feel that way and you’re wrong. I’m sure I was right about that.

You worked with Jack again on How Do You Know, his last film. Did you get any indication he would step back from filmmaking?

I wouldn’t be surprised to see Jack work again. I mean, it’s been a hunk of time but I don’t know. Maybe it could be the right thing. He’s reading scripts all the time, I think.

You’re still in touch?

Yeah, yeah.

Do you talk basketball? I know you’re an avid Clippers fan while he, obviously loves the Lakers.

Yeah, we do. He’s one of the best. It’s amazing. He’s not just a manly man but he’s got all the graceful stuff about him, too. He has it all. He’s also a tremendously sophisticated guy in terms of literature, in terms of art. I mean, he really knows his stuff. He’s a first-rate painter, too.

How many of your former collaborators are you close with?

Albert for sure. Albert and I go back forever. The group that I did Taxi with, we still hang out. We Zoom together and we still know what’s going on in each other’s lives. It’s great. Everybody’s still working and doing well and that feels good. I have that experience as a spine.

Gracie Films is a huge part of your success. How do you define the company’s ethos? Has it changed over the years?

It hasn’t changed over the years, and it’s that writers control their work. They don’t get rewritten by somebody else. That has never happened, and I don’t think it ever will, and that’s the deal.

Ella McCay is your first movie in a while. Will it be your last?

I have notes on the next one.

You do?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. I have a dream of where and when I want to do it. And I have notes on it already. I will be at work on it when I finish this one.

This story appeared in the April 2 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Source: Hollywoodreporter