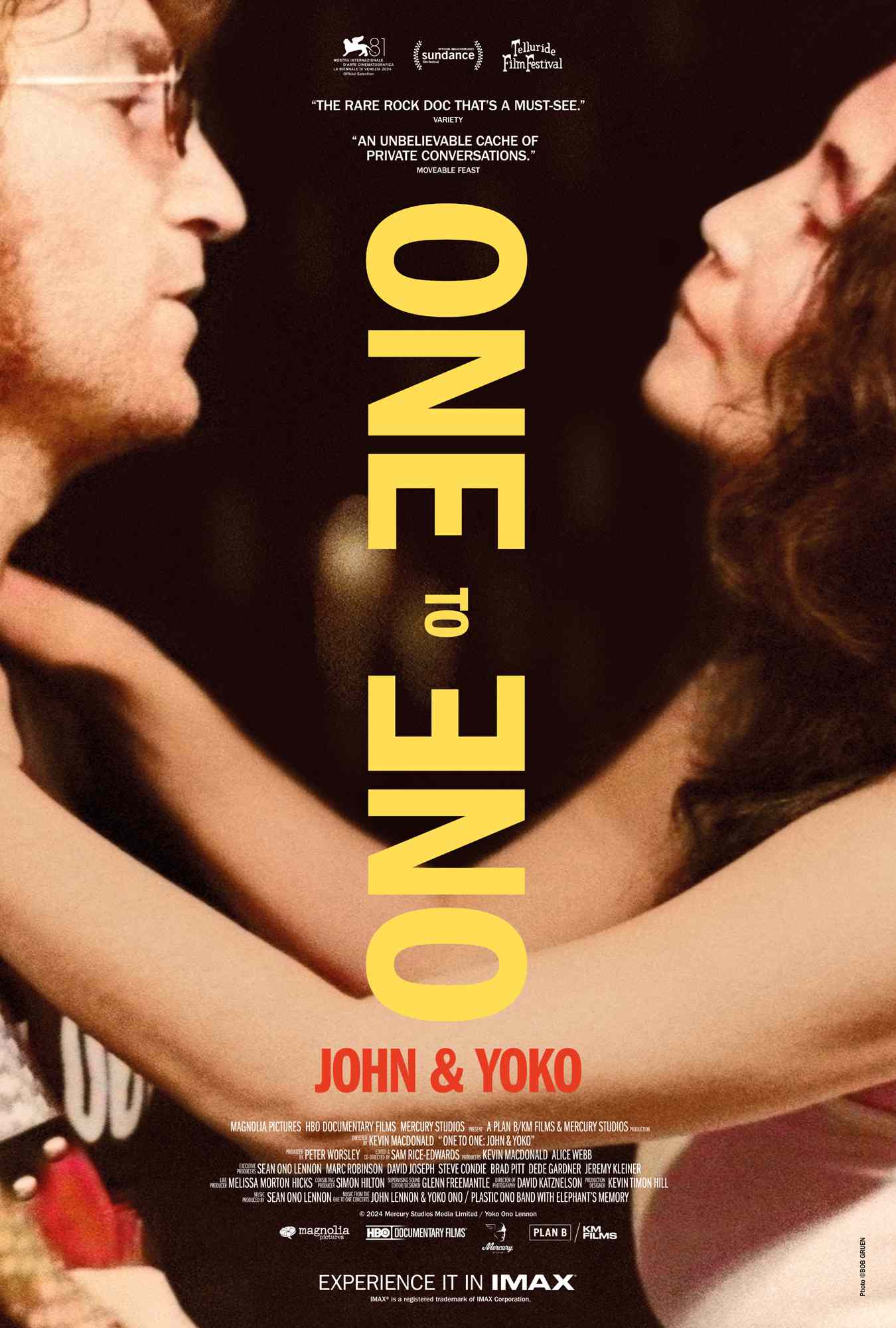

Exploring Yoko Ono’s Journey: A Director Unveils a Unique Perspective on Motherhood and Heartbreak in the New John Lennon Documentary

- One to One: John & Yoko showcases footage from the only full-length concerts Lennon performed after the Beatles — now stunningly restored in IMAX with a powerful remix by Sean Ono Lennon.

- The documentary features unheard private phone calls that capture unfiltered moments of Lennon and Ono’s life, from politics to personal pain.

- The film reframes their U.S. move as a search for Ono’s kidnapped daughter, Kyoko — a heartbreaking story that shaped much of the period for them.

At a time when it seems like there’s little new left to say about any of the Fab Four, One to One: John & Yoko — which begins its IMAX run on April 11 — is both revelatory and daring.

Co-directed by Oscar winner Kevin Macdonald and Sam Rice-Edwards, the documentary explores perhaps the least celebrated period of John Lennon and Yoko Ono’s life: their first 18 months as New Yorkers. Upon their arrival in August 1971, the pair found themselves in a country electrified by sociopolitical change — and they inadvertently became a lightning rod. Their shockingly accessible Greenwich Village home drew all manner of avant-garde artists, leftist activists, and self-proclaimed freaks, who descended in droves to convince the world’s most famous couple to attach themselves to their pet projects and causes. More often than not, they obliged.

Lennon and Ono were also at turning point. Settling into their new home, they were simultaneously adjusting to a post-Beatles existence and grappling with the fact that the ideals and optimism that had carried them through the ‘60s might not be enough to remold the world as the utopia they imagined. Liberal presidential candidate George McGovern was trampled in the ’72 election by the corrupt Richard Nixon administration, which had a vested interest in getting Lennon and Ono deported. Radical hippie heroes like Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman began to go off the rails, and the peace movement as a whole started to lose its efficacy. The question of the period — for Lennon and Ono, and the country as a whole — seemed to be: “What’s next?”

The politicized mood of the period is ultimately responsible for the two primary source materials that make up One to One. The first is footage from a pair of benefit shows for the Willowbrook State School staged by Lennon and Ono at Madison Square Garden on Aug. 30, 1972. The visuals have been restored to pristine clarity and the audio given a punchy remix by Sean Ono Lennon, who serves as the steward of his parents’ creative archive. The result on the big screen is amazingly transportive. Lennon’s blistering renditions of classics like “Instant Karma” and “Come Together” are made all the more astonishing when you consider that these are the only full-length concerts that he ever performed away from the Beatles.

The film also draws from previously unheard phone calls taped by Lennon and Ono as a safeguard against FBI wiretapping ordered by Nixon’s government. The intimate recordings feature candid conversations with their friends and associates. Most crucially, they provide the heartbreaking context for the pair’s move to the U.S., as Ono searches for her missing daughter Kyoko, who was kidnapped by her ex-husband, Tony Cox.

The tapes and concert footage are woven together with television clips from the period: everything from news reels to vintage TV ads. For Lennon, one of the great self-confessed couch potatoes of the 20th century, the television represented his chief conduit of information. (It’s perhaps not a surprise that Lennon and Ono made numerous high-profile appearances on chat programs like The Dick Cavett Show and The Mike Douglas Show in this period.) More than just cinematic connective tissue, the impressionistic clips transform the TV into a character in itself.

The end result is a nonlinear yet totally immersive experience that truly makes viewers feel as though they’re sitting with Lennon and Ono in their Greenwich Village apartment. In fact, Macdonald and Co. painstakingly recreated the home on a soundstage for the film. It’s this kind of exhaustive effort and loving attention to detail that makes One to One stand out amid the bumper crop of recent Beatles-centric offerings.

There are many themes that run through One to One, but above all, it’s a film about retaining hope amid the fear of starting over. After this period, Lennon and Ono would never again court the world’s attention with ambitious conceptual stunts or overt political protests. Instead, they adopted an approach of thinking globally and acting locally. In addition to the concerts, Lennon and Ono hosted a Central Park picnic for children of Willowbrook, who had been subjected to horrific conditions at their school. Lennon and Ono’s dreams of saving the world may have been dying, but at least they could try to save the neighborhood. “OK, so flower power didn’t work,” Lennon told the audience at one rally. “So what. We start again.”

PEOPLE’s spoke with the One to One co-director Scott Macdonald about the making of the film and how it changed his view of the iconic duo.

When describing this documentary to friends, and I keep going back and forth on whether to lead with the concert footage or the taped phone calls. Either one would be more than enough to anchor a documentary, but the fact that you have both is truly remarkable. Which provided the seed of this project?

The seed of the documentary was the concert footage. The producer, Peter Worsley, had been trying to get the rights to use it in a documentary for a while because he knew that Sean Lennon was trying to remix it. One of the reasons the footage was rarely seen — it was only ever released on VHS in 1986 — was because it was very badly recorded. I think everyone involved was stoned or drunk. [laughs] It was only in the last few years that we’ve had these incredible advances in sound technology and sound remixing. A huge amount of work was done by Sean to basically restore that footage and remix that audio to create a fair representation of what it would have been like attending the show at Madison Square Garden. The producer persuaded Sean and his family to let him make a film using that footage and this remixed audio, and I was lucky enough to be asked by the producer to take a look at it and come up with an idea for a documentary.

I love how you structured the documentary like someone flipping through TV channels. How did you land on that approach?

I heard some interviews with John talking about how much TV was important to him at that time in particular. I thought that would be an interesting way to make a film about the America which John is learning about and living in, and how that changes him. I built a reconstruction of the apartment he was living in when he first moved to New York, where he watched TV on this very big television at the end of his bed. It’s basically a one-room apartment he and Yoko live in, in the West Village, and they’re there for 15 months. So I thought, “Okay, I’m gonna make that 15 months the focus in my film and tell the story of how this concert came about in a non-literal way.” I wanted to really try to get inside the head of John and Yoko at that period.

The aspect of the documentary that intrigued me the most when I first heard about it was the cache of taped phone calls. Was there anything in those tapes that came as a surprise?

More than any particular thing, I was mostly just surprised that these tapes existed at all. It was just this record of day-to-day stuff, from the totally banal to the really fascinating. There was Yoko opening up about the Beatles breakup, John expressing his political enthusiasm and all this crazy stuff about Bob Dylan. It just felt like, “Oh my God. If you’d been hanging out with them in that apartment in 1972, this is the stuff you would’ve heard, in these words.” That was super exciting.

I think if you’re a serious Beatles scholar, you’re not going to walk away from this film and go, “Oh, I learned XYZ from it.” There might be a few things that you didn’t know, but it’s more gonna be that you feel like you’re actually getting to know them — the real them — through home videos and the phone calls in particular. It’s very intimate. I loved John in so much of this because he feels so open and so enthusiastic about things. He’s trying to figure out, “How do I now live my life? I’m an ex-Beatle. I’m 31-year-old. I’m one of the most famous people in the world. I have all the money I’m ever gonna need.” Nobody had done that before, really. I think John was always very concerned with “How can I make myself a better person and how can I help the world be a better place?” You feel him grappling with those questions and I think that’s so interesting.

Yoko shone through in a way that I feel she hasn’t in so many other docs. It feels like we get to see more of her and get to know her better, which is so great. The speech she gives at the international feminist conference was so powerful. And there’s a clip of the telephone audio where she elaborates on the public perception that she’s this evil woman who split up the Beatles. Viewers really get to see a different side of her in this documentary.

That was a big aim of mine. [When I was first asked to direct this], I was originally like, “Oh God, do I wanna do a film about a Beatle? There have been so many — what else is there to say?” And it was only when I started to look through the material that I thought, “Oh yeah, there’s actually things in here which feel totally new to me in terms of the connection they give you to these characters.”

And I think part of that was Yoko and the loss of her daughter, Kyoko, who’d been kidnapped by her ex-husband. The child grows up in a sort of Christian [sect], and Yoko doesn’t see her for 25 years. This is a story that was never a secret, but nobody seems to know about it. When I first heard it, it made me feel totally different about Yoko, because you realize all this period, she was a mother in pain who’s trying to find her child. I think that explains why John and Yoko connect to the Willowbrook story so much. She’s a mother who’s seeing these children in pain, and she’s thinking about her own child who she can’t help.

I thought it was central [to the documentary]. I want to make people understand what that must have felt like for her. When I heard the recording of Yoko singing “Age 39” [a.k.a. “Looking Over from My Hotel Window”] at the feminist conference, I thought that just expresses it all. She sings the line, “If you see my daughter tell her I love her. She haunts me in my dreams, and that’s saying a lot for a neurotic like me.” It’s so completely revealing and open — you really feel it. So I thought, “That’s got to be the core of this film.” Somehow or other, that got lost in the maelstrom of everything else that was going on. Bringing that emotional truth back to the center of things is what we tried to do.

In some ways, I think the film is about children and childhood. You have John’s own admissions about his pain as a child and how he was messed up by his mother’s death and how that has sort of driven him to ask questions about himself. It’s why he’s so “chippy,” as he says, or has a chip on his shoulder, but it’s also why he’s so open to new experiences. And with Yoko, she’s missing a daughter. So she has this pain about childhood, too. And then the Willowbrook footage is the thing that spurs them to do the only full-length concert that they ever do. There’s something about that which just feels very poetic and speaks to the deepest emotional wounds in them.

I always felt like this initial New York period was the most under-discussed period in John and Yoko’s lives — which is funny because they were so active and probably did more media appearance than they ever would. It’s an era of hope followed by immense disappointment, politically and socially. That obviously seems to mirror a lot of what’s happening now.

One hundred percent. [John’s grappling] with “How do we change the world? Who am I?” All those questions. And then Nixon wins reelection, and I think it sets off a lot of firecrackers inside John’s head. He’s not quite sure where to go. [The mirroring] wasn’t intentional, but when we started looking at all this TV footage of the period, you start to see so many things that recall today — whether it be the first Black woman running for president, Shirley Chisholm; whether it be the attempted assassination of the populist politician, George Wallace; whether it be concern over war that’s roiling the campuses. And there was also this political fight. The left was kind of at a dead end and fighting against this incredibly well-oiled machine of Richard Nixon. It was a corrupt machine. All these same issues that preoccupy America today were also preoccupying it back then.

But I take from this film a sense of hope. John and Yoko’s journey in the film is trying to change the world politically to trying to change the world personally, individual by individual. When you see those kids in Central Park and John’s singing “Imagine,” and you realize he’s gonna make these kids’ lives better, you think, “Well, that’s not changing things in a big political way through the whole nation, which is what he wanted to do, but it’s making certain people’s lives better.”

I feel like the most crucial line of the documentary was when John tells the audience, “OK, so flower power didn’t work. So what? We’ll start again.”

That goes right to the heart of it. John was an idealist, and that’s what’s appealing about him. This guy is wearing his heart on his sleeve. He is so passionate. It’s really endearing. I think that that willingness to be naked and exposed is very unique to him as a celebrity. For them, it became about moving beyond mainstream politics. It hasn’t worked, and it seemed like it wasn’t the way to promote change.

There’s a great piece by Sheri Linden in The Hollywood Reporter where she writes, “There’s an urgent question at the heart of Macdonald’s documentary: Was all that apathy-fighting hope and activism naive?” I was curious about your answer to that.

It’s a good question, isn’t it? In some ways, you listen to John in this film and you think, “Yeah, there is a naivety there.” But I think the line between naivety and hope and optimism is very thin. At this moment, we all need a sense of hope and optimism about the future. And I think John Lennon personifies that. I think it’s more than just naivety. That’s certainly part of it and it can be read like that at certain times. But what’s moving about it to me is that John is constantly looking for ways to both make himself a better person, but also for ways to improve the world around him.

Source: People

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the celebrity section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.

Related Posts

- Unveiling Coachella 2025: Exciting Lineup of Special Guest Performances Revealed

- Charlie Brooker Unveils Insights on ‘Black Mirror’ Season 7 Conclusions and Potential Future Installments

- Samuel Goldwyn Films Secures North American Rights for the Hilarious Sci-Fi Comedy ‘Cold Storage’ from Studiocanal

- Lizzo’s Transformative Health Journey: Unveiling Her Insights on Weight Loss and Wellness

- Insights from an Emerging Director: Exploring the Unique Tone of DC’s Lanterns