Revelations Director Yeon Sang-ho Interview: Alfonso Cuarón, Intention

Prolific Korean director Yeon Sang-ho has staged a zombie apocalypse aboard a bullet train (Train to Busan) and a twisted supernatural fantasy across the full expanse of Seoul (Hellbound) but with Revelations, his latest feature for Netflix, he wanted a more intimate, grounded story.

Revelations follows a pastor who comes to believe that murdering the culprit behind a missing-person case is his divine mission and a police detective haunted by visions of her late sister who was driven to suicide after becoming the victim of a heinous crime. The film was shot almost entirely on location with natural light, lending its high-concept story a gritty sense of immediacy.

Revelations was executive produced by multi-Oscar winner Alfonso Cuarón, who began following Yeon after his animated Korean feature debut King of Pigs premiered to acclaim at the Cannes Film Festival in 2011. After Train to Busan became a global phenomenon in 2016, earning nearly $100 million and reinvigorating Korean action cinema, the celebrated Mexican auteur reached out to ask Yeon if they could somehow work together. “I was blown apart because it’s one of those perfect films,” Cuarón says of Train to Busan in a statement provided by Netflix. Years of creative correspondence followed and Revelations is the result, with Cuarón serving as executive producer of the project.

Revelations stars Ryu Jun-yeol (A Taxi Driver) as Pastor Sung Min-chan, Shin Hyun-been (Reborn Rich) as Detective Lee Yeon-hui and Shin Min-jae (Parasyte: The Grey) as the story’s ostensible villain, Kwon Yang-rae. The project is co-written by Yeon’s regular collaborator Choi Gyu-seok, who also adapted the story into a popular Korean webtoon.

Revelations began streaming worldwide on Netflix last Friday. The Hollywood Reporter recently connected with Yeon over Zoom to discuss the genesis and intentions of his morally complex thriller.

What were the creative origins of Revelations?

I developed this project together with my regular collaborator, writer Choi Gyu-seok. We were actually brainstorming for season two of our Netflix series Hellbound, and we came across this term called pareidolia, which means the human brain’s tendency to try to make sense of things that are actually random and senseless. I thought this concept was very intriguing, and it could allow us to delve into human fragility, human nature and our deepest feelings. But I didn’t think it was very fitting as a concept for season two of Hellbound, because that’s a bigger-scale project with a lot of fantastical elements. A new story was required to really do justice to the concept. So that’s how Revelations started.

And then how did the characters come to you as a way to flesh out the themes you were interested in — the initially timid-seeming pastor and the detective haunted by loss?

The character Sung Min-chan, the pastor, is a person who tries to justify his materialistic greed — and when he loses objectivity with his faith, he spirals downward. That’s the downfall of his character. After coming up with him, I wanted someone who’s like a thematic opposite, a mirror image of this guy. That’s how I came up with the detective character, Lee Yeon-hee. She sees the villain character, Yang-rae, as a demon because of what he did to her younger sister. Ultimately, though, she has to look into his past and confront her own trauma in order to save the girl. It’s very ironic to me that she has to do that.

Yeah, I found it interesting how they move in opposite directions with their belief about Yang-rae. The pastor initially sees him as a person in need but comes to believe that divine revelations have revealed him as a demon deserving the ultimate punishment, whereas the detective begins with total condemnation but has to move towards humanism. I really liked the line from the psychiatrist near the end, where he says that most tragedies are caused by a combination of complex circumstances beyond our control or understanding and that we invent devils or simple stories for justification. What did you want to say about human belief and redemption with this film?

The characters in this film try to make sure they have one clear answer for their tragedy, and that is what leads to their trauma and further tragedy. Personally, I think redemption doesn’t come from having a clear answer about what went wrong, but rather from continually asking yourself questions. That process of self-questioning is what brings about redemption.

Shin Hyun-been as Detective Lee Yeon-hui.

In recent years, you’ve been working regularly with Choi Gyu-seok on the stories for your web comics and films. How does the creative process across those two mediums work for the two of you? And how do you think the web comic form has influenced your filmmaking? Your films are immaculately constructed, and the themes they raise are very deep, but the style of expression in the storytelling can be quite simple, or archetypical, in a way reminiscent of comics.

When Choi Gyu-seok and I collaborate, we sit down and brainstorm ideas together to set the tone and direction for the story. Then I start writing the script, and once I share that with Choi, he handles the comic adaptation totally on his own. I don’t intervene in that part. He really uses the strengths of the comics medium, sometimes adding things that aren’t in the script, or using techniques unique to comics. When adapting it into a film or series, we try to take the best of both mediums. If Choi added something great to the comic, I might try to include it in the film. That’s how we work. I certainly do think web comics have had an influence on my filmmaking. One of the reasons I love working with writer Choi is that we went to the same college and have been good friends since our early 20s. We know each other really well. So when I send him my script, he immediately understands what kind of tone and visualization I’m going for. We both influence each other creatively.

The other creative relationship we have to discuss is Alfonso Cuarón. Can you tell me how you first got to know Alfonso?

Alfonso Cuarón’s production company reached out to me and said he would love to collaborate. He said it didn’t have to be in English — it could be a Korean film — and he was fine with that. So we had a call. Most non-Korean audiences know me from Train to Busan, and I told him that Revelations would be very different from Train to Busan. He actually liked that — that I would be trying something different. He also told me that he had seen my earlier animated works The King of Pigs and The Fake, so he knew me from way back, even before most people overseas did. Because he was already familiar with my work, I felt at ease discussing the project with him. If he had only wanted something like Train to Busan, I probably wouldn’t have been interested. But he was very respectful of my creative vision. From the script writing through editing and promotion, he was always checking to make sure the original vision was maintained. I’m very grateful for that.

Did he give you any specific notes or feedback on the script or cuts of the film — or other ways he was helpful to you?

One thing I really remember is the oner sequence at the very end — the climactic fight scene with the three characters. It’s about five minutes and 30 seconds, done in one continuous take. I was heavily influenced by Alfonso Cuarón’s work when creating that scene, and he gave me a lot of great feedback. He really loved the one-scene, one-cut approach and explained what he liked about the camera work. Alfonso Cuarón is known for amazing long takes in his films, like in Children of Men and Gravity, so that was very gratifying. Korean directors of my generation are all influenced by his work. The finale of Children of Men really influenced the finale of Train to Busan. He’s truly an inventor when it comes to filmmaking technique. He’s always trying new things, and we all want to learn from that.

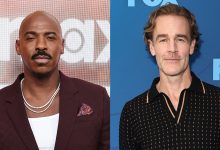

From left: Ryu Jun-yeol as Sung Min-chan, Shin Min-jae as Kwon Yang-rae in Revelations.

One thing that struck me about the film was the richness and naturalism to the cinematography and locations. It felt that you chose to use a lot less CG than in much of your recent work. What were your intentions with the film’s style?

For this movie, it was really important to me that the audience feel like this is a realistic, grounded story. For example, there are a lot of rainy scenes, and we actually shot all of them during real rain. Our crew constantly checked the weather forecasts to time things right, and we got lucky. Regarding the divine revelations Min-chan sees, there’s a scene when he goes to the senior pastor’s room and sees the face of Jesus in the arrangement of objects along one wall. That was actually made with props and lighting — no CGI. Interestingly, the more out of focus the camera was, the more realistic the face looked, which aligned well with the film’s themes. We did use a bit of CGI for the angels he sees in the sky in another moment, but that was also mostly natural clouds, and overall, I wanted to go as raw and real as possible.

Another thing I liked about the movie — especially at the beginning — is that it puts the viewer in a similar position to the characters: the pastor looking for signs of God, the detective seeking clues. We’re also scanning the screen for significance, asking ourselves what the meaning might be to that water that’s dripping ominously. Was that intentional — to put the viewer in a similar mindset of searching for meaning?

Yes, exactly. I wanted the audience to question their own beliefs. For instance, with the kidnapped girl, Ah-yeong, we originally had scenes showing she was alive, but we took those out on purpose. I wanted the audience to wonder is she alive or dead, and what does that mean for the story? That uncertainty makes them question their own assumptions. And, for example, after the girl is saved, there’s a tight shot of a window that kind of looks like a cross. Maybe some viewers will think this was all truly divine — like it was all intended by God. I wanted to leave room for those interpretations so people would be torn between different ideas.

Are you Christian yourself?

There’s the question of: If you go to church, can you call yourself Christian? I do go to church, but I think it’s a deeper thing. It’s something you have to keep asking yourself.

Source: Hollywoodreporter