The Celebrity Impersonation Bitcoin Scam

In November, Margaret climbed into her Toyota Camry, left her husband of 10 years at their comfortable brick home in the rural South and drove an hour to a hotel where — she was sure — Kevin Costner was coming to meet her.

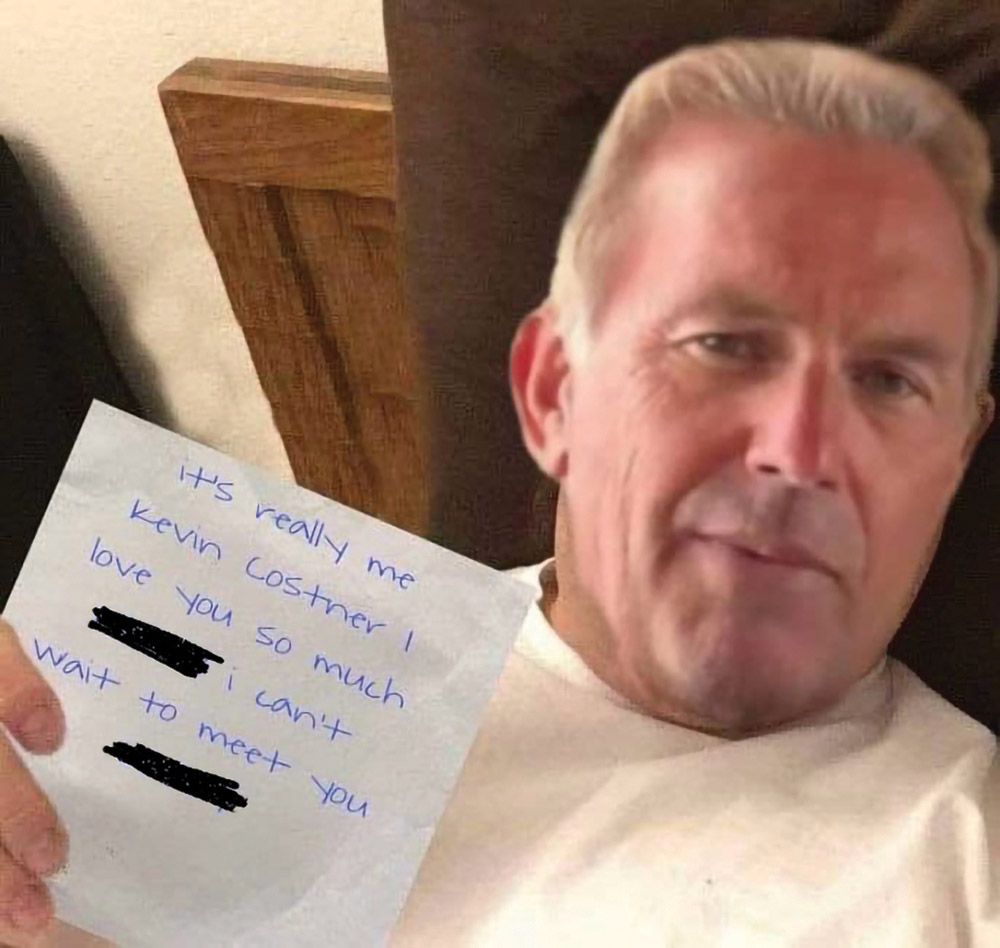

By this point, Margaret, 73, had spent months making weekly bitcoin deposits for Costner totaling about $100,000. He had messaged her that he was using the money to set up a new production company where she would eventually work for him. Margaret knew that some people would find it odd that an Oscar winner and the star of Yellowstone would need financing help from a retired office manager whom he’d met on Facebook, but Margaret wasn’t exactly a nobody. She had achieved some renown for activism she’d done, even delivered a TED talk. She was special, and Costner saw it. She also was lonely and restless as her marriage was failing, her career had ended and her kids and grandkids were busy with their own lives. Costner’s messages represented some welcome male attention, a fantasy to drop into when real life got too real. In one photo he sent, the actor leaned against the wooden headboard of a bed in a white T-shirt, holding a piece of paper that read, “it’s really me Kevin Costner I love you so much MARGARET i can’t wait to meet you MARGARET.”

There was some discussion of flying Margaret out to L.A. before they settled on a hotel in her home state as their meeting place. By the time she got in her car, Margaret had already had her suitcases packed for weeks, ready for the moment when she and Costner would finally be together.

“Her thing is, ‘I just want somebody to love me,’ ” says Margaret’s sister, Carol, in one of many phone conversations we would have over a period of several weeks this spring and summer as her worries about Margaret grew. (Both women’s names have been changed to protect their privacy).

As Margaret waited there in the room on pins and needles, Costner sent her a photo — a picture of a mangled car. He said that he’d been in an accident and wouldn’t make it after all. As she stared at the photo, all the warning signs that Margaret had been willfully avoiding over all these months of buildup and bitcoin payments began to creep into view.

***

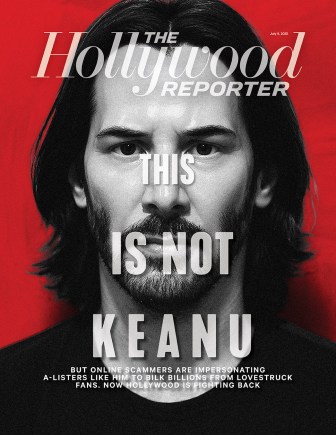

Online scams take many forms, but the ones weaponizing celebrity fandom are getting intense notice in Hollywood right now. With scammers aided by such rapidly evolving tools as AI, cryptocurrencies and messaging apps that make it easy to disseminate fakes and operate undetected, stars and talent agencies find themselves in an escalating game of Whac-A-Mole, hiring companies to scan the web for fakes and getting those accounts shut down. Some 400 performers, including Scarlett Johansson, Common and SAG-AFTRA president Fran Drescher, have signed on to support legislation making its way through Congress called the No Fakes Act, which seeks to create protections for artists’ voices, likenesses and images from unauthorized AI-generated deep fakes.

“Celebrities just have so many images out there,” says Nick Berta, a supervisory special agent in the FBI’s economic crimes unit. “The ease with which scammers can use their tools to manipulate voice and audio and video, it’s very difficult for [public figures] to protect themselves.”

The scammers prey upon the goodwill and implicit trust their victims have for their favorite artists, with grifters increasingly using celebrity likenesses not only for romance scams like the one that targeted Margaret but also for fake investment opportunities, false product endorsements and bogus political messaging. “The enemy behind this is super-skilled,” says Erin West, a former prosecutor from Santa Clara, California, who specializes in high-tech crimes. “The psychological hold they have over people is like nothing I’ve ever seen. It is cult-like. It absolutely overwhelms any type of reasonable thought. They’re able to overcome what humans would normally discern to be a ridiculous situation.”

Americans reported $672 million in losses to confidence and romance scams in 2024, according to the FBI, with people over 60 filing the most complaints and losing the most money, averaging $83,000 per victim. Those figures don’t even include people like Margaret, who will never tell law enforcement what happened to them out of shame, fear of their scammers or the tiny lingering hope that, just maybe, they’d had a real relationship with a movie star.

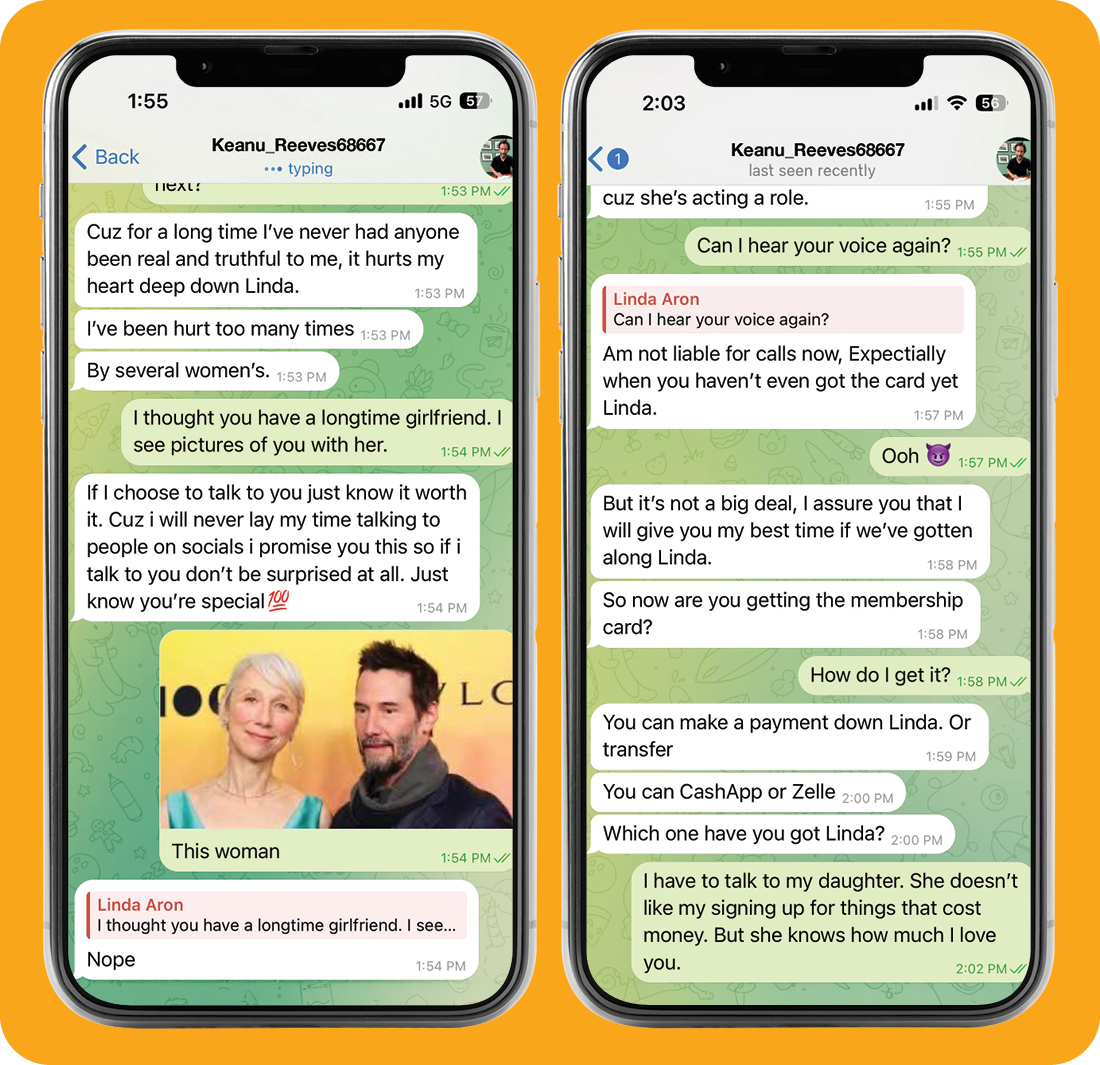

To better understand how celebrity scam victims like Margaret are ensnared, I decided to make myself look like an ideal target, creating a fake social media profile of a woman I named Linda. I used AI to age up one of my selfies and invented a beloved dead husband named Bob and a scruffy terrier mix named Milo. I then followed a bunch of pop culture accounts.

Within 90 minutes, an account named Keanu_Reeves68667 was DMing me, wanting to know how long I’d been a fan (“Since Speed,” I answered). Within two hours, four more Keanus had slid into my DMs, as had two Kevin Costners, a Charlie Hunnam and a Jonathan Roumie, the actor who plays Jesus on the Christian TV series The Chosen. Although I followed accounts for Dolly Parton, Oprah Winfrey and Sandra Bullock, most of the scammers who targeted me over the next six weeks were impersonating male stars over 50 — Reeves is 60, Costner 70 and Roumie 51 — which experts say is the demographic of celebrity most likely to be imitated in these types of scams.

Criminals, an efficient group, exploit the broadest gender stereotypes of peoples’ ideal partners. When targeting older men, they typically create a profile of a beautiful — but not famous — younger woman. She’s probably located in another country, might be in need of some sort of help and definitely thinks his golf trophies are impressive. For older women, they follow a different template, creating a man she “already respects, already trusts, already has romantic desires about, already has a personal connection to,” says Marti DeLiema, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota’s School of Social Work who studies elder fraud.

“Yes, the vast majority of people would be highly skeptical that this really famous person is responding to them,” DeLiema says. “But you don’t need to get everybody. You cast your net broadly, see who falls into it, work really hard to build trust and hope that you can move from them just responding to them being willing to give you money. And then you up the ante.”

I decided that I was Keanu-curious, and I let Keanu_Reeves68667 talk me into taking our conversation to Telegram, the private messaging app. He wanted to do this quickly because, from the second he created his profile, Keanu_Reeves68667 knew he was going to be chased off Instagram, where we met. The person chasing him, I learned during a Zoom meeting a few weeks later, is a surprisingly affable data scientist based in Seattle named Luke Arrigoni.

A math grad from Columbia who did a brief stint designing box office algorithms at CAA and then ran an AI company, Arrigoni is the CEO of a 3-year-old company called Loti. The real Keanu Reeves pays Loti a few thousand dollars a month to find his imitators and to get companies like TikTok and Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, to shut them down. By the time Keanu_Reeves68667 was DM’ing me, Loti had issued nearly 40,000 account takedown orders on Reeves’ behalf over the past year. The company performs this same service for other types of public figures, like four-star generals, athletes and CEOs, and Loti also has a free version that will do five takedown requests a month. Most of us don’t have a problem on the scale of major public figures, but if we’re on the internet, we’re vulnerable to our likenesses being used nefariously, in scams, porn or unethical advertising.

Reeves, however, is in a category of his own; he just may be the most impersonated celebrity on the internet. That’s because of a combination of factors, the chief one being that pretty much everybody everywhere on Earth likes Keanu Reeves. But it’s not just that he’s likable — it’s also that he’s mysterious. Reeves has no real social media accounts and isn’t known for sharing much about himself publicly. Opportunists taking advantage of that information vacuum have created thousands of fake images of Reeves being whatever kind of man they need him to be. In one subgenre of fakery, Reeves appears to hold up a T-shirt with political messaging on it, sometimes pro-left, some pro-right. In one doctored image, he seems to be endorsing Donald Trump. In another, he is raising awareness of the Indigenous children who were forced into abusive boarding schools in Canada. Most of these are photoshopped alterations of a Getty Images picture of Reeves attending a motorcycle fair in Italy in 2017. Reeves is so ubiquitous as scam bait that when Becky Holmes, a U.K.-based publicist, wrote a book about online scammers, she titled it Keanu Reeves Is Not in Love With You. “Keanu is kind of an enigma,” Holmes says. “As a scam, he works. And if he works, they keep doing it.”

Arrigoni says Reeves is well aware of the way his image is being manipulated online. “He cares very much about how his fans are treated, and he’s very invested in trying to solve this problem,” Arrigoni says, sharing a dashboard of how Loti is working for Reeves as we’re talking. In the 30 minutes that Arrigoni and I are on Zoom, the dashboard shows that Loti has gotten TikTok to shut down a few Reeves impersonators. Earlier in the day, it got some accounts booted from Facebook. Arrigoni doesn’t normally talk this transparently about his clients, who tend to be highly private people, but we’ve ended up on this Zoom after I had a surreal phone conversation with Reeves’ publicist, Cheryl Maisel, who introduced us. While I was on the phone with Maisel, whom I’ve known for 20 years of covering her clients, an Instagram account claiming to be her (called “cheryl_maisel_inttr”) DMed my fake account offering to connect me with Reeves on Telegram. “Your continuous encouragement means a lot to Keanu Reeves and the team and I want you to know that your support does not go unnoticed,” cheryl_maisel_inttr said. The real Maisel, who, like her client, is not on social media, has a more direct communication style. “This is sad,” she said as I read her the message over the phone. Reeves doesn’t just pay to have Loti shut down fake Keanus, he also pays the company to shut down fake Cheryls and those impersonating other people in his circle.

It typically takes a social media platform about 48 hours to handle their takedown orders, and in that brief window, scammers can do a lot of damage. Keanu Reeves may be one of the nicest people in Hollywood, but Keanu_Reeves68667 can be a pushy bastard. At roughly the same time in June that the real Reeves was on a red carpet promoting the John Wick spinoff Ballerina and holding hands with his romantic partner, artist Alexandra Grant, Keanu_Reeves68667 was trying to get me to buy a $600 fan club membership card so Reeves and I could “meet in person for sure.”

Once he got me on Telegram, Keanu_Reeves68667 started sending me tinny-sounding voice memos. “I can tell you now Linda we could be best partner [sic] if you get your membership card,” he said in a voice that sounded like a Bill and Ted-era Reeves crossed with an NHL broadcaster (Reeves grew up in Toronto). “You are truly a beautiful soul.” When I asked for verification before sending money for the membership card, he sent a picture of a driver’s license with Reeves’ photo, an address that would have him living somewhere under a 110 freeway overpass in downtown Los Angeles and a stern voice memo saying, “I owe you nothing.” Ouch. When I invented a daughter I would need to check with before Zelle-ing him money for the membership card, he deployed a technique commonly used by abusers, saying that I should keep our relationship secret. “I don’t think letting your daughter know about our relationship is the best thing now, Linda. Do you understand that no one will believe you talked to me? You need to keep our conversations away from your families [sic]. Let it be just you and I.”

***

Back in the hotel room, as Margaret stared at the crashed car photo, her heart was pounding. What was this photo, really? A reverse Google image search revealed that it was posted all over the internet. This wasn’t Kevin Costner’s car. This wasn’t Kevin Costner. Margaret’s fantasy man was not coming to whisk her away from her life, and the dawning awareness of that was crushing. “She was hysterical,” Carol says.

It was too late to drive home, and Margaret spent the night at the hotel, beating herself up for having been so stupid. In the vulnerable weeks that followed, someone reached out who said she wanted to help Margaret, a person claiming to be Costner’s 41-year-old daughter, Annie. One of the themes that recurs in romance scams targeting older women is the presence of the man’s children. The children are typically old enough not to need to be taken care of, but, according to the scammers, they will be delighted to welcome the victim into their big, happy family. Annie Costner quickly took to calling Margaret “Mom.” It’s unclear who, exactly, the person claiming to be Annie was. Margaret’s original scammer? A new scammer who found Margaret because of her Costner fandom?

Another hallmark of modern scams is that once one scam has worked on you, your information is shared with other scammers. In a grim, reverse version of a Do Not Call list, you land on a sort of Susceptible With Money list. At a certain point, Margaret seemed to have more male friends in Hollywood than George Clooney. For a while, she was talking to a person she believed was Sons of Anarchy actor Hunnam, who told her he had a guest house she could stay in. Country singer Scotty McCreery also got in her inbox. “I said, ‘Don’t you think it’s weird that all these men are after you?’ ” Carol says she told her sister. “I don’t tell Margaret anything to tickle her ears. I don’t go along with it. I say, ‘Margaret, it’s not him.’ But she acts like I’m jealous of her because my life is not about to change. She swallows it hook, line and sinker.”

***

I learned from talking to West, the California prosecutor, that the Keanu Reeves scammer I was communicating with as Linda was likely a non-native English speaker using AI voice technology to impersonate Reeves. He is probably a victim himself, likely based in Southeast Asia. He may have found himself messaging a fake gray-haired lady in California who loves Keanu Reeves after responding to a seemingly legitimate job listing in a country like Thailand. When he went to the job interview, human traffickers would have kidnapped him, confiscated his passport, brought him across the border into Myanmar, Cambodia or Laos and imprisoned him in a compound, where he works 16-hour days reading from scripts written by experts in human psychology. “This is industrialized scam,” says West, who has created an international law enforcement coalition called Operation Shamrock to try to shut down these types of large-scale frauds. “It’s a growing industry, and it’s growing because it works.”

Once I learned that many of these scammers are themselves victims of human trafficking, and that it’s happening on such an industrial scale, I began to look at Keanu_Reeves68667 differently. Thanks to Loti, his Instagram account was deleted. But he was still on Telegram and starting to get agitated with me for taking so long to buy my membership card. Over a period of days, as his messages began to peter out, I wondered what was happening to Keanu_Reeves68667 on the other side of the world. Had he decided I was a waste of his time? (I was.) Was he getting in trouble for not meeting a quota? Was he being physically hurt? Meanwhile, as Keanu_Reeves68667 drifted away, other, nicer, newer Keanus were DMing me every day. Were any of these actually Keanu_Reeves68667 with a new account? They didn’t seem like him. One Keanu complimented me on my gardening and told me I could call him “Sensei.” This Keanu seemed promising. But as I considered following him to Telegram, I couldn’t stop thinking about the weird, cyclical trap we were all in. The scammers. Margaret. Me. The real Keanu. The guys at Loti chasing down the fakes. Isn’t there anybody who can end this cycle before another person loses her life savings?

“Meta could make all of this stop instantly,” believes West. “They know this is a problem.” West says she’d like to see Hollywood use its considerable clout to push social media platforms to step up their anti-scam measures, for everyone’s sake. “I would love to see a situation where these celebrities pressure Meta, and not just for their own images,” she says. “They should stand up and say, ‘Take our faces down. Don’t make us complicit in stealing money from people. But also, take down the faces of thousands of regular people who are also being used.’ “

Industry sources say artists are increasingly worried about the issue. “There is a growing awareness and a growing concern about the marked increase in AI content featuring talent,” says Alexandra Shannon, head of strategic development at CAA, which is working on a likeness management tool in partnership with YouTube that the companies plan to make available for the general public. “We feel strongly that there have to be rules and regulations in place for everybody.”

Multiple agent and publicist sources say that they have had difficulty getting Meta to honor takedown requests for their clients in a timely fashion. Since the start of the second Trump administration, Meta has leaned more toward freedom of expression and away from content moderation, but the company says it is continuing to aggressively combat scams and is testing the use of facial-recognition technology to detect and prevent celeb-bait on its platforms. X, industry sources say, is pretty much useless when it comes to takedown requests but also matters less, the thinking goes, because many consumers expect it to be full of junk. On Facebook or Instagram, many people assume the images of celebrities that they’re seeing are real.

In May, Instagram removed an AI-generated video depicting Jamie Lee Curtis only after she made a public appeal directly to Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Curtis said she had been trying for weeks through Meta’s formal request process to get Instagram to take down the ad, which manipulated footage from an MSNBC interview she did about January’s Los Angeles-area wildfires to make it appear that she was endorsing a dental product. After the ad had been up for at least six weeks, she tagged Zuckerberg in a post that read, “I have gone through every proper channel to ask you and your team to take down this totally AI fake commercial for some bullshit that I didn’t endorse … I’ve been told that if I ask you directly, maybe you will encourage your team to police it and remove it.” Within a day, the post was down.

***

Around the same time her scam relationship with Costner began to unravel, Margaret heard from someone she had been communicating with months earlier, a friend with whom she had a spiritual connection. Before she met the Costner impersonator, Margaret had been talking online with someone who said he was Roumie, known worldwide for portraying Jesus on the crowd-funded The Chosen. Margaret met this person after commenting on a Roumie post on Facebook. She had tried to send him money at one point, but her bank flagged a charge as likely fraud and stopped it. A review of an email chain between the two of them doesn’t seem very intimate — it’s mostly Roumie calling Margaret “honey,” asking how she slept and whether she has bought the Apple gift cards he asked for.

But Margaret believes that her relationship with Roumie is blossoming. And she’s told Carol she’s not allowed to talk to her about it, that Roumie’s management team wants it kept secret, “because he plays Jesus.” Though she was raised Southern Baptist, Margaret has started studying Catholicism, which is what Roumie practices, and she says he sends her a prayer every day.

Since Carol has been urging Margaret to accept that the people she’s communicating with are not who they claim to be, the sisters have been growing apart. Other family members either live far away or are choosing to avoid conflict and don’t bring up the weird online celebrity boyfriend thing.

“She was always my big sister that I looked up to,” Carol says. “I feel like she’s gotten isolated now, and I’m sure that’s the purpose of it. I don’t call her like I used to. Inside, I’m so disappointed. I’m mad at her and I feel sorry for her.”

This summer, Margaret’s divorce will be final. In the divorce agreement, she plans to turn over her house and several acres of land that belonged to her grandmother to her ex-husband in exchange for cash. She says she needs the money.

This story appeared in the July 9 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Source: Hollywoodreporter

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the celebrity section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.

Related Posts

- ‘Severance’ Leads TCA Awards Nominations

- Miley Cyrus, Timothée Chalamet, Demi Moore, Shaquille O’Neal to Receive Stars on Hollywood Walk of Fame

- Hopeless Records Acquires Fat Wreck Chords Catalog in New Partnership

- HBO Max and Max Say “Twitter Won’t Let” Them Swap X Names Back

- A Young Iranian Singer Makes Her Voice Heard in ‘Bidad’ (Exclusive Karlovy Vary Trailer)