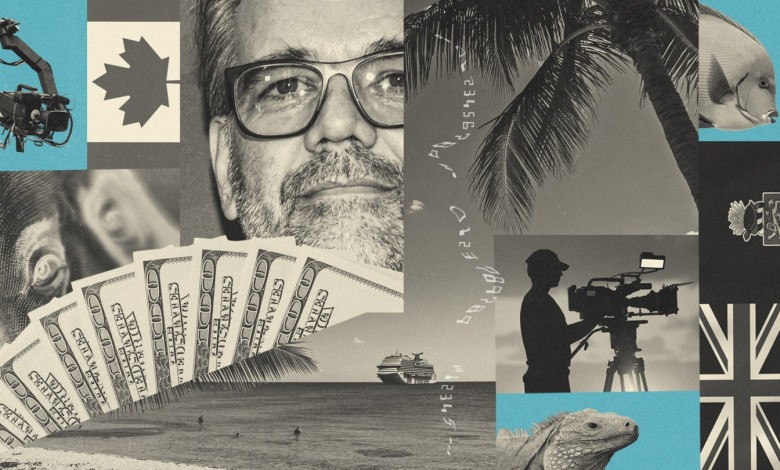

The Fatal Ponzi Scheme That Rocked the Industry

In 2024, Ron Perlman was at work on a long-gestating Ernest Hemingway movie alongside his backer, Canadian film financier William Santor, with whom he’d made several projects during the preceding years in the Caribbean. “It culminated in a location scouting trip together in Cuba,” the actor says. “It was mind-blowingly positive. I thought we’d be in preproduction shortly thereafter.”

Santor, who’d recently thrown his 50th birthday party at the penthouse of The Ritz-Carlton Grand Cayman along world-renowned Seven Mile Beach, had become a Caymans kingpin, socializing with everyone from high-ranking public and private sector island insiders to expat Armie Hammer. He was especially known for his generosity in hosting cast-and-crew dinners during productions. “He liked to be the cool guy with the cool wines,” recalls a frequent attendee.

Figures such as Santor are prized in indie filmdom, where money is scarce and, even when found, usually available with frustrating strings attached. Santor offered the holy trinity: He was affable, disinterested in creative meddling and, most importantly, came with an open checkbook. Everyone in the scene dreams of securing such an easygoing, deep-pocketed benefactor.

Which is why his dramatic and tragic unraveling — first professional, then personal — has been so unsettling to those who knew and came to rely on him. The consequences have been far-reaching for a moneyman who, it appears, was running a spectacular fraud.

“He just seemed like a guy enabling filmmakers to live their dreams,” says Perlman, explaining that it’s “been a shock to the system.” The actor adds of Santor, “He could greenlight your film. When you meet someone like that, you go with the flow.”

Indie film’s perennial money mania has long made it susceptible for trouble. In the 1970s, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was famously funded by mobsters, leading to years of legal drama. In the 1980s, a would-be producer of The Cotton Club who made her fortune in the cocaine underworld ended up hiring hitmen to kill a rival on the project. Since then, there have been headline-garnering cases of accounting fraud (surrounding Battlefield Earth) and money laundering (the sovereign wealth fund that financed The Wolf of Wall Street).

The Santor scam, which plays into the global arms race around tax incentives, shines a klieg light on the often opaque realm of film finance. And it’s stung Canadian pensioners, Caymanian locals and Hollywood creatives alike.

Not long after that scouting trip with Perlman, Santor’s company Productivity Media Inc. was in Ontario bankruptcy court, with CEO Santor himself accused of misappropriating at least $31.7 million. By December, a court-appointed receiver filed an injunction prohibiting him from disposing of assets in the Caymans, including a vast real estate portfolio, cash in a slew of Caribbean bank accounts, luxury goods like jewelry, wine and watches and a fleet of vehicles, including a Bentley Bentayga.

Weeks later, Santor, a married father of two young girls who’d turned Grand Cayman into an unlikely production hub, had died by suicide at an island property he’d allegedly purchased and been renovating with laundered funds whose market value is more than $7 million. Records indicate that the swindled are primarily working-class Canadian retirees: plumbers, pipe fitters, electricians, roofers and iron workers.

There’s perhaps grim irony in Santor’s noir-inflected end. His lurid saga — set in the tropics, the plot revolving around deceit and a dead body — would be just the sort of onscreen story PMI specialized in financing.

Before his con caught up with him, Santor financed multiple film projects starring Ron Perlman in Day of the Fight.

Jeong Park/Falling Forward Films/Courtesy Everett Collection

***

Santor, the son of schoolteachers, grew up on a farm outside Ontario. He was a swimmer who competed nationally in the backstroke. “It’s a personality type where you’re just always yearning: that extra millimeter, that extra millisecond,” he told an entrepreneurship podcast in 2023. He studied kinesiology in college, then got involved in the professional Latin ballroom dance world. But Santor shifted to a more lucrative career path after he witnessed the financial havoc his father’s death had on his mother. He soon found employment in Canada’s private wealth management sector, working for family offices.

Looking for a specialty where he wouldn’t be competing on deal flow, Santor eventually segued into independent film finance when he learned about Canada’s rebates system. These refundable tax credits allow companies to receive cash even if their tax liability is zero. He became a bridge financier, establishing PMI to fund the gaps across different phases of film production. His firm leveraged these credits as well as presales and distribution rights in pursuit of profit.

PMI’s model, reliant on a long-established program run by the Canadian equivalent of the IRS, allowed it — at least in theory — to lower the risk of lending money to indie filmmakers, a notoriously risky business. “The ups and downs of what’s happening at the box office and in streaming is less of a driver for us,” he shared on a business podcast in 2024.

By his account, Santor wasn’t concerned about his lack of experience in the film finance sector. “The old quote is that it’s your attitude, not your aptitude, that determines your altitude,” he said in the 2023 interview. “So many people set their own limitations before anyone else sets anything for them.”

PMI soon made a name for itself in Canada. For several years, it threw parties during the Toronto International Film Festival, where the likes of Barenaked Ladies and DJ Jazzy Jeff performed. Among its financed productions were Aubrey Plaza‘s buzzy indies The Little Hours in 2017 and Black Bear in 2020.

Aubrey Plaza in Black Bear.

Momentum Pictures/Courtesy Everett Collection

***

Then came the pandemic. At its onset, Santor and his family were vacationing in the Cayman Islands. The tropical archipelago was sealed off before any COVID cases materialized. Soon, as the costs associated with pandemic health safety protocols for film shoots had begun adding at least 20 percent to revised budgets, Santor sensed an opportunity in turning the coronavirus-bubbled Caymans, whose economy was hitherto known for offshore banking and cruise ship tourism, into a production hub.

Despite virtually nonexistent production infrastructure, PMI over the next two years backed half a dozen Cayman-shot movies, typically budgeted between $5 million and $10 million and starring the likes of Harvey Keitel, Iggy Pop and Don Johnson. More than 100 crewmembers were employed, the majority of whom were Canadians flown in on a private jet rented from the Toronto Maple Leafs.

Cayman government officials were happy to help. “We’d pick up the phone, and they’d move mountains to make things happen,” Santor recalled on the 2023 podcast. “As you can imagine, for them, the thing that the Caymans was most known for, from a film and television perspective, is The Firm” — Tom Cruise‘s 1993 legal thriller about shadowy financial dealings in the Caymans — “which didn’t paint the island in a great light. So, they’re like, ‘This will help change the narrative of what the island is about.’ “

The Caymans has spent the decades since The Firm‘s release seeking to shed its lawless reputation as a haven for tax evaders, money launderers and organized crime figures to bank via shell companies and anonymous accounts.

Santor’s 2020 production pivot proved fateful for the islands, whose national airline has since inaugurated a nonstop route from LAX. The country of nearly 90,000 people has also recently launched its own film incentives program, offering up to a 35 percent rebate, and since PMI began backing features, the Caymans has hosted unscripted productions like HBO Max’s dating show FBoy Island and Freeform’s reality series Grand Cayman: Secrets in Paradise, whose cast includes Hammer’s ex-wife, Elizabeth Chambers.

“Hindsight is always 20/20,” says a source involved in PMI’s Caymans productions. “But we never saw anything shady [about Santor] on the ground. Which is why we’re so taken aback by what’s come out. I mean, clearly he had more on his mind than ripping people off, or he wouldn’t have spent all this time on the island creating this very real thing.”

Santor was granularly involved in the Caymans production scene he’d ignited. Perlman, who starred in PMI’s 2023 action thriller The Baker, recalls that Santor was “a great collaborator: there every day, generous, life-affirming. You don’t see a lot of that in the business.”

As his profile began to grow on Grand Cayman, Santor became known for securing the best tables at restaurants and riding a scooter through island traffic, blithely ignoring suggestions to put on a helmet. “In L.A., he’d be just another AFM character, making these lower-budgeted movies with bigger names,” explains one Caymans associate, referring to the American Film Market. “But here he was a big fish.”

Gene Hackman (left) and Tom Cruise in The Firm, a 1993 legal thriller about shadowy financial dealings in the Caymans.

Courtesy Everett Collection

***

In December 2023, Colleen Camp, producer of four PMI films, began to raise an early alarm with her business partners over what appeared to be financial irregularities across projects. In retrospect, she says, the promise of Santor was probably too good to be true, citing his bankrolling of her critically acclaimed boxing drama Day of the Fight: “Who else would give Jack Huston $10 million to direct a black-and-white movie made with Michael Pitt?” Camp adds, mordantly, that she had a bad premonition when she first learned of the prospect of shooting films in the Caymans. “I’m thinking about The Firm, of course,” she says, “and that I’m going to be on a boat that explodes.”

PMI began an initial probe of Santor in April 2024 after learning from the leader of one of its international sales partners that he’d asked the executive to sign an audit confirmation letter for loans that didn’t exist. A whistleblower email to PMI four months later alleged a range of misconduct: that its portfolio included more than $70 million in fraudulent films; that its legitimate library was significantly overvalued; and that Santor had diverted funds from some productions by instructing distributors to send money to an account he personally controlled.

The Ontario bankruptcy filings detail a Ponzi-like scheme in which “imposter corporations” were created to divert invested funds for personal gain. False email addresses and websites associated with partnered sales agents and distribution companies were created to carry out the plot.

Then, to avoid detection, partial repayments were made with money obtained from other fraudulent loans. The elaborate deception also was concealed by blaming the chaos of the pandemic as well as the Hollywood labor strikes, which roiled real production cycles during this period.

In hindsight, there were warning signs. The firm had gap-financed 2018’s Stockholm, starring Ethan Hawke and Noomi Rapace. Its distributor, Dark Star, found it notable that its checks weren’t being cashed. “I knew something was strange when Will went to the Caymans,” emphasizes Dark Star president Mike Repsch. “That was always a little suspect to me.” A producer on a PMI project that later shot there, and who elected at its outset not to be party to the film’s LLC out of concern about its legitimacy, notes that the “Cayman Islands is always a red flag. My spidey sense went right off.”

***

A Canadian financial risk analyst tells THR that Santor’s premeditated misconduct is rare: “In this case, it seems like it was malicious from the beginning, whereas most fraudsters don’t intend to defraud. Somehow their business plan goes wrong, and one lie leads to another lie. They make a bad investment and try to recoup the loss by making another bad decision.” This person believes that Santor was either actively or passively aided, explaining, “It’s hard to believe that his business partners didn’t know what was going on, that they were so dumb to not see anything happening.”

The bankruptcy filings allege that PMI’s CFO Andrew Chang-Sang, a certified public accountant who held 25 percent of the company’s voting shares, was aware of Santor’s scheme and financially benefited from it, including through “misappropriated” funds that resulted in the purchase of a villa in the affluent Spanish coastal town of Málaga. The August 2024 whistleblower claimed he also used impersonating email addresses and forged signatures on audit confirmations.

For his part, Chang-Sang tells THR in a statement that he was “shocked” when he learned of Santor’s fraud, as “there had been no indication of any concerns from PMI’s professional advisers, including its auditor.” He observes that he and other PMI senior executives authorized an independent forensic review and provided the evidence necessary to obtain the receivership order. “I have acted responsibly, diligently and in good faith at all times and have sought to comply with my legal obligations,” he explains.

Dark Star’s Repsch only learned that Santor had impersonated him and his company when THR contacted him. “This is confusing, as you can imagine,” he says. “Will had this big personality, a bravado, that filled the room.” He pauses, then adds: “I don’t know. I think of his kids.”

A well-regarded independent film producer marvels at what’s happened with PMI — but isn’t surprised, given the baseline of the sector. “In this part of the business,” the seasoned dealmaker explains, “if the money’s green, nobody’s asking questions.”

***

To work in the Wild West of independent film is to live with a tolerance for risk unknown and uncountenanced in the major studio business. It’s both badge of honor and monkey on the back. Santor knew this. “I’ve been teetering between ‘What a prick!’ and ‘What a nice guy!’ ” says a colleague who collaborated closely with him in the Caymans.

If William Santor was, as it appears, a con artist, he achieved his aims like all such swindlers: by exploiting not just his marks’ trust but the unique vulnerabilities inherent in their dreams. Which is to say, he understood that modern Hollywood’s green light, which year by year recedes from filmmakers with their arms outstretched, was the ideal bait for his larger scheme.

This story appeared in the Sep. 3 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Source: Hollywoodreporter

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the movies section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.

Related Posts

- 'The Conjuring: Last Rites'

Giles Keyte/Warner Bros.

Share on Face…

- Telluride Awards Analysis: For ‘Ballad of a Small Player,’ Colin Farrell Is Back in Oscar Mix for Second Time in Four Years

- Margaret Atwood Takes Satirical Shot at Controversial Alberta School Book Ban

- Radiohead Announce First Tour Since 2018

- From left: Nesbat Serhan, Motaz Malhees, Saja Kilani and Clara Khoury in 'The Voice of Hind Rajab.'

Mime Films, Tanit Fil…