Who Really Took the Iconic “Napalm Girl” Photo? Director of New Doc Addresses the Controversy (Exclusive)

As the lights came on at the Sundance premiere of the documentary The Stringer last January, there was no doubt for many viewers that one of the most important photos in the history of journalism — the Pulitzer Prize–winning 1972 snapshot titled The Terror of War — has been misattributed. In the months since, the controversy over who really took the devastating Vietnam War image better known as “Napalm Girl,” which put a heart-wrenching human face on the horrors of the conflict and helped galvanize the anti-war movement, has only grown, even though the film has not been released and no distributor has been announced.

The photo was taken after a napalm attack in the South Vietnamese village of Trảng Bàn. There were a number of journalists, cameramen and photographers positioned on a road as a naked nine-year-old girl named Phan Thi Kim Phuc fled the attack with others. The film uses archival footage, testimonies, forensic recreations and other means to investigate who really took the photo.

For the first time, in an exclusive interview with The Hollywood Reporter, the film’s director, Bao Nguyen, addresses the controversy over what has happened since the intense night of the premiere.

The film makes a strong case that the the photographer long-credited with taking the photo in 1972, Nick Út, a young Vietnamese AP staffer at the time, did not take it and that a man ignored by the mainstream for 50 years, Nguyễn Thành Nghệ (pronounced “Nay”), who was a freelance photographer, did.

In the world of photojournalism, it was as shocking a conclusion as if someone proved that Woodward and Bernstein did not do their own reporting on the Watergate stories that led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon.

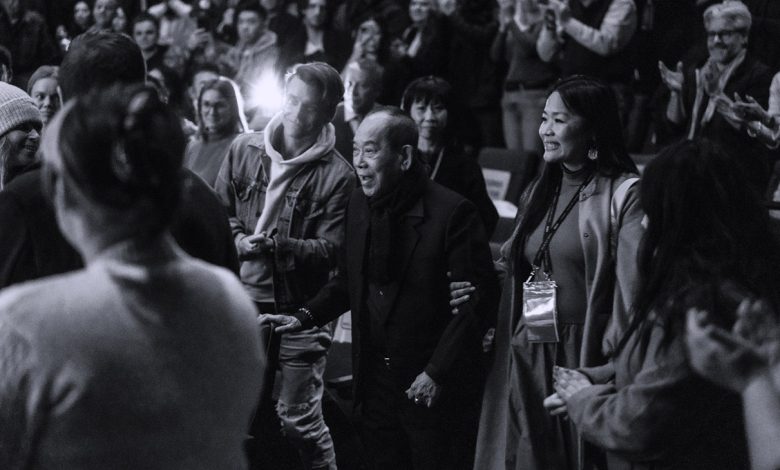

Attendees of the Sundance premiere of The Stringer on Jan. 25 were surprised to learn after the screening that Nghệ himself was in the audience, frail but standing proud, saying in Vietnamese-accented English, simply, “I took the photo.”

Nguyen’s film chronicles the work of investigative journalists Gary Knight, Fiona Turner, Terri Lichstein and Lê Văn as they tracked down the origins of the photograph through the fog of war and time.

THR’s Sheri Linden praised The Stringer’s restrained structure as “the stuff of Conrad or Dostoyevsky.”

Yet The Stringer has been met with silence, or worse, contempt from many corners of the journalism world, with defenders of Út posting extensively on public and private social media. On May 6, then, the Associated Press announced that it had completed its own supposedly thorough investigation of the photo’s attribution. AP concluded that Út was in a position to take the photo and said it would continue to credit the photo to him.

On May 16, 10 days later, the influential Amsterdam-based foundation World Press Photo reached a different conclusion, determining that there was a good chance Nghệ or another photographer had taken the image and decided to suspend Út’s credit.

Út’s lawyer James Hornstein, who has called the film “defamatory,” issued a statement that World Press Photo’s decision was “deplorable and unprofessional” and “reveals how low the organization has fallen.” Út, now 74, had a long career in photojournalism and received plaudits for decades for The Terror of War.

In the wake of the recent announcements, Nguyen vows that one way or another the film, with new additions since Sundance, will be released this year — and expressed his own surprise at the reception The Stringer has received in the journalism community.

This interview was done the day the World Press Report was released and has been edited for length and clarity.

***

You’ve been busy.

Bao Nguyen: Honestly, I don’t ever want to be the center of the story.

Why does the World Press Report matter?

World Press is one of the leading voices in photojournalism and their investigation, as opposed to AP, was independent. AP was from what I gather an internal investigation looking at a former AP employee, And, I’m not a journalist by any stretch of the imagination, but … .

Well, that’s not true, but OK.

For me, I’m observing the truth in a way, while Gary Knight, one of the main subjects of our film, is pursuing truth. There’s that slight distinction.

But World Press spoke to outside experts and forensics scientists to make their conclusion. They haven’t changed or suspended a credit to a photographer [before] in their 70 year history, which is incredible. I applaud World Press for what they did and the evolution from what their executive director said when the film premiered at Sundance to their investigation since then. They’re very thorough, and they essentially agreed with the forensics and the findings in our film.

World Press Photo executive director Joumana El Zein Khoury has written two pieces about The Stringer. In them, she admits her initial reaction after the Sundance screening was to come to a quick decision about the photo’s authorship, but that she decided the organization should conduct a more thorough and thoughtful investigation.

When Nghệ showed up at the screening, I wondered why this guy wasn’t getting a bigger standing ovation. Have you been surprised by all the pushback that you’ve gotten?

We were just happy that Nghệ could be there in his frail state. (Nghệ is in his late 80s). I can just tell you from speaking to him, it was a very emotional moment for him and the family and for him to be definitive in the Q & A and say, “I took the photo,” which for me is bigger than any standing ovation. It is a unique experience when we’re bringing on the subject [of a documentary]. We were surprising the audience, too. They didn’t know he was there, and so I think it was still a very powerful moment and I wouldn’t change it for the world. As for the debate over the attribution of the photo, we knew that it wasn’t about relying on these institutions that have become the arbitrators of legacy and historical record for decades. It wasn’t about waiting for them to bestow something to me as a filmmaker. It was about Nghệ. Having the chance to tell the world his truth and his story and his perspective on something that happened 53 years ago.

To some extent it’s not really the AP’s story to tell. In a way, it kind of doesn’t matter what they say.

For me as a filmmaker, it was always, How do I listen to a story that someone has been telling within his own circles for so long, but never felt like they had the agency to stand up and, and say it publicly in a way that would be heard.

Have you been surprised at the reception among journalists?

I’ve been surprised by people’s opinions towards something that they haven’t watched, to be honest, especially among journalists. I grew up near Washington, D.C. I always dreamt of being a journalist and I wrote briefly for the NYU newspaper. I soon realized that I am bad at deadlines, and so I realized I wasn’t the right person to be a journalist. I didn’t have that intense attitude of going towards a story and getting that news very quickly. I think filmmaking fits my more reflective intention on life and storytelling. And, yeah, it surprised me that there were so many journalists who I’ve respected over decades that were angry that we asked the question — or that Gary Knight, Terri Lichstein and Lê Văn asked the question — of whether Nick Út was the person who took the photograph.

I always felt that journalists were in the pursuit of truth. They’re not necessarily the arbitrators of truth. But to ask the question, I think, is a key pillar of journalism, and so that surprised me — and again it surprised me that people who haven’t watched the film made a judgment on the authorship. But you know, to be fair too, a lot of people who were adamant about Nick being the author are close friends of Nick or know Nick. Having a relationship with someone over decades, you would trust someone, right? I mean, you build that trust. I try to empathize and humanize that perspective as well. But I was surprised by the reaction from many journalists in that world.

The other thing that you don’t see in the news reports but you do see in the film is that Nghệ was probably the best trained photographer on the scene that day, and if you had to pick who was going to make a photo like that, he’d be a good candidate.

When I learned that in the process of making the film, it definitely made me more firmly believe that Nghệ was the one who took the photograph.

Is there any doubt in your mind who took it?

I don’t ever try to speak in absolutes. I truly do believe Nghệ is the one who took the photograph.

A lawyer’s job is to defend their client, but what do you think of Nick Út‘s lawyer’s questioning of the documentary process, questioning the journalism?

I’ve tried to stay away from those conversations and those debates. I think there’s imperfections in the AP report, for example with the claim that everyone who is still alive from that day was interviewed in that report. Trần Văn Thân — the NBC sound person who, if you watch the film, was part of that cluster of journalists who could have taken the photograph — Thân was never interviewed in the AP report, and he is one of the living witnesses to that event. What’s interesting from a filmmaker’s perspective too, is that he was a sound person, and I think a lot of directors who work with really good sound people realize how much it’s not just about listening. A great sound person has to watch, has to look, has to observe. So he was the most, probably the most observant person on that road, in that group of people. And he said he witnessed Nghệ taking the photograph. I find it strange that AP didn’t interview him, especially as he is also one, if not the only, living Vietnamese witness, in addition to Nghệ, that could prove that Nghệ took the photograph. One of the themes of the film itself is that Vietnamese voices have been erased from the telling of this.

Asked to comment specifically on whether the AP’s investigation was done without bias and why Thân was not interviewed, Patrick Maks, the Director of Media Relations and Corporate Communications for The Associated Press, forwarded the statement issued with the release of the investigation. The statement says, in part: “AP’s extensive visual analysis, interviews with witnesses and examination of all available photos taken on June 8, 1972, show it is possible Ut took this picture. None of this material proves anyone else did. Our investigation has raised significant questions, which are outlined in the report, that we may never be able to answer. Fifty years have passed, many of the people involved are dead and technology has limitations. Maks also asked that links to the AP report, and an interactive feature be included in this article.

How has the fight from Út’s friends in journalism, and the threatened legal action, made it a challenge to find distribution?

We are still in advanced negotiation for worldwide distribution. I think actually the debate and the conversation around the film makes it more relevant globally. It opens it up to audiences to kind of make the decision on their own. And I think that engages audiences in a much more complex way than having this sort of smoking-gun, definitive answer. I haven’t been the one at the forefront of the negotiations about distribution, but I do think that [the debate] continues to push the film into the sphere of conversation. I can’t tell you how many people have reached out to me asking to see the film from around the world. I mean, I made a film called Greatest Night in Pop [about the recording of the star-studded single “We Are the World”]. When I made that film, I also didn’t think that the song “We Are the World” had such a global reach, but it did. And this film, The Stringer, has an exponentially larger reach than I had ever imagined with Greatest Night in Pop.

When might people be able to see it?

We’re in negotiations for worldwide distribution, and we expect to share the film this year with audiences around the world. For me, no matter what, this film is gonna be shared around the world this year because it’s so important for me to share Nghệ’s story. We got a message from Nghệ’s’s daughter today that Nghệ heard the news from World Press. He is in a frail state, but she shared to us that he felt a little better today. And that means a lot to me as someone who has been entrusted to be the custodian of his story. That gives me a bit of hope.

Source: Hollywoodreporter

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the celebrity section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.

Related Posts

- ‘Harry Potter’ Stars Talk Universal Epic Universe’s Ministry of Magic and Thoughts on Upcoming Series

- Josh O'Connor in 'The Mastermind.'

Mastermind Movie Inc

Share on F…

- Kate Mara Talks Treating Tim Robinson Movie Like a Drama

- Farmer Wants a Wife: Why John and Claire Won’t 'Put Pressure' on an Engagement After She Was 'Surprised' to Be His Pick (Exclusive)

- Nick Kroll Reveals Lady Gaga and Howard Stern as the Two Stars ‘Big Mouth’ Just Couldn’t Get