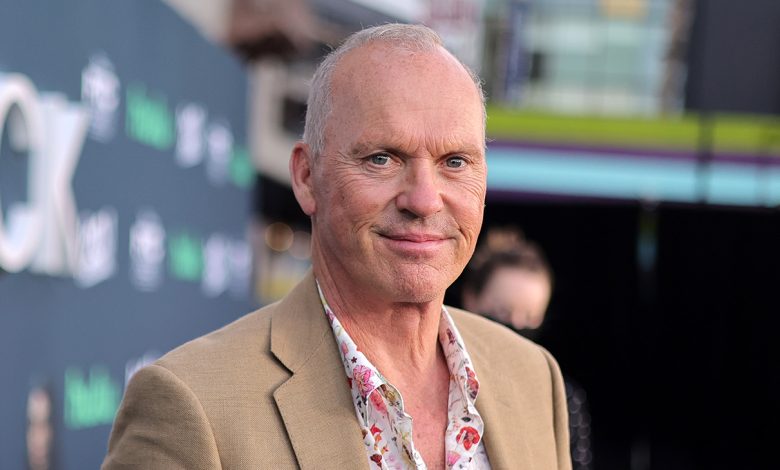

Michael Keaton Hints He’s Ready to Change His Name Professionally

Michael Keaton may be changing his name, professionally.

The actor, who was born as Michael Douglas, wasn’t able to use his birth name when he began his career as the Screen Actors Guild disallows its members from using the same name professionally as other actors. Since both Michael Douglas and Mike Douglas were taken, he had to find a new surname.

He ended up selecting his now-famous moniker in an unexpected way. “I was looking through — I can’t remember if it was a phone book,” the actor told People magazine. “I must’ve gone, ‘I don’t know, let me think of something here.’ And I went, ‘Oh, that sounds reasonable.’”

Now after more than 30 years, he tells People, he’s ready to update his stage name to Michael Keaton Douglas. The name was meant to make its debut in the film he recently directed, Knox Goes Away, but that didn’t pan out.

“I said, ‘Hey, just as a warning, my credit is going to be Michael Keaton Douglas.’ And it totally got away from me. And I forgot to give them enough time to put it in and create that. But that will happen,” he said. However, his credit in the upcoming Beetlejuice sequel will appear as “Michael Keaton.”

Much like Keaton is returning to his roots with his professional name change, he is revisiting one of his most iconic roles in Tim Burton’s new film. During a press conference at the Venice Film Festival, the actor explained how Beetlejuice has evolved in the new installment. “I think that it’s obvious that my character has matured,” he said. “As suave and sensitive as he was in the first, I think he’s even more so in this one. Just his general caring nature and his sense of social mores and his political correctness.”

Source: Hollywoodreporter

Related Posts

- Roundball Rocked: With NBA Return Looming, NBC Purges Scripted Roster

- SoundCloud Says It “Has Never Used Artist Content to Train AI Models” After Backlash on Terms of Service Change

- Fox News’ Camryn Kinsey Is “Doing Well” After Fainting on Live TV

- Kerry Washington and Jahleel Kamera in 'Shadow Force.'

Courtesy of Lionsgate

…

- This Alternative Artist Landed a Top-20 Chart Debut With an Album Made Almost Entirely on His Phone