‘You’ Season 5 Finale and Joe’s Brutal Ending Explained: Interview

[This story contains MAJOR spoilers from You season five, including the series finale, “Finale.”]

The showrunners for You season five had one goal heading into the hit Netflix show’s final season starring Penn Badgley as the infamous Joe Goldberg: “We just need to see the monster for what the monster is.” They accomplished just that with the series finale, “Finale.”

اRelated Posts:

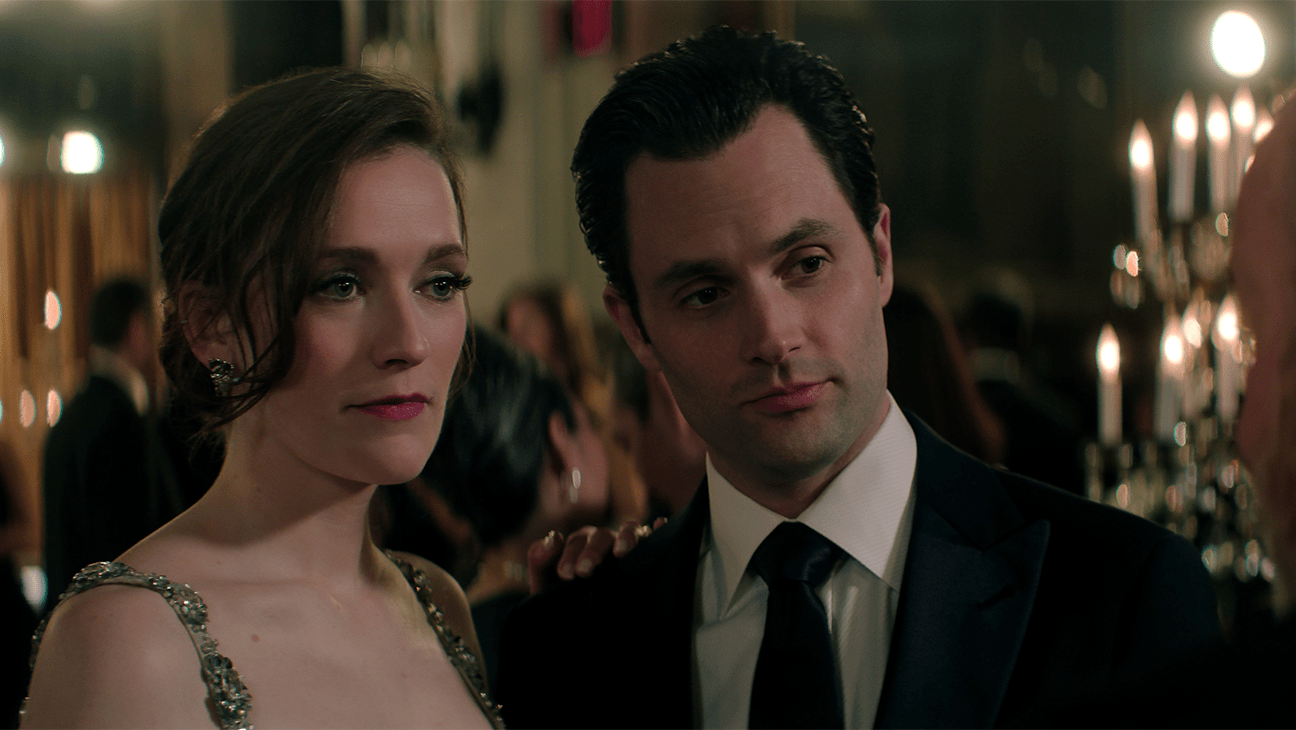

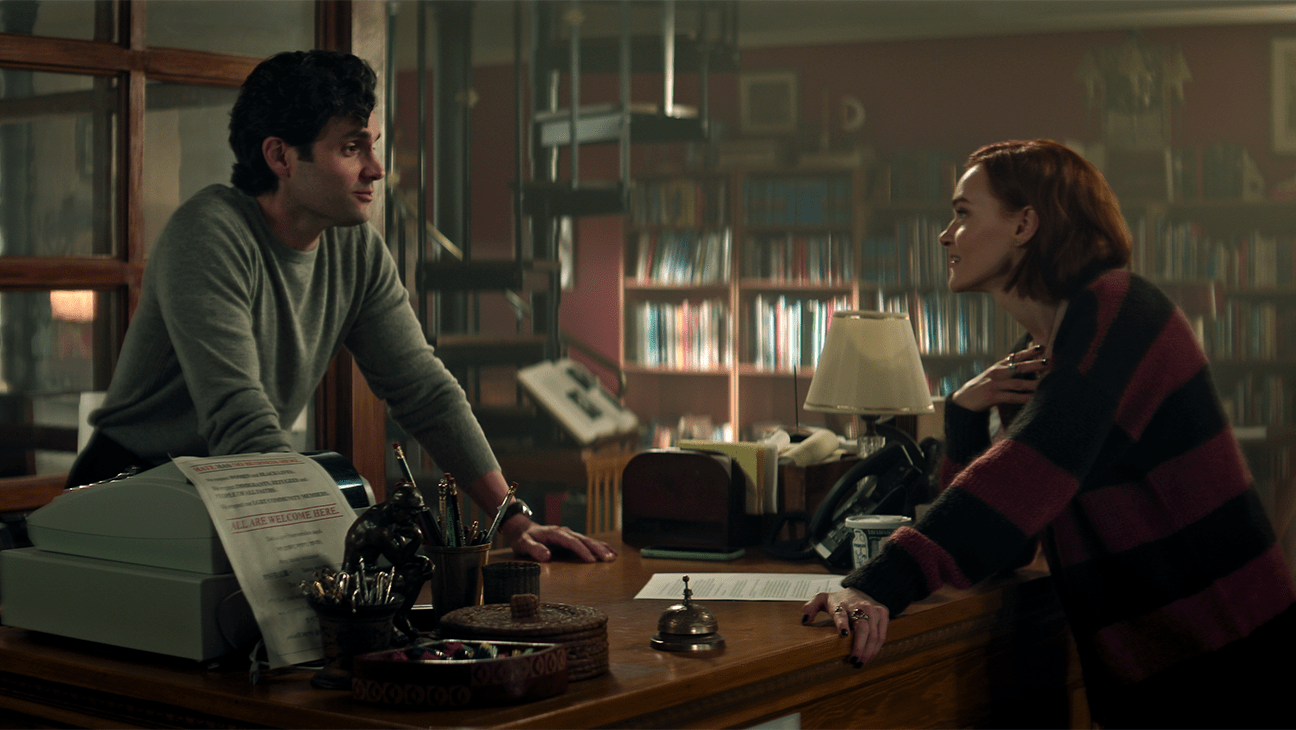

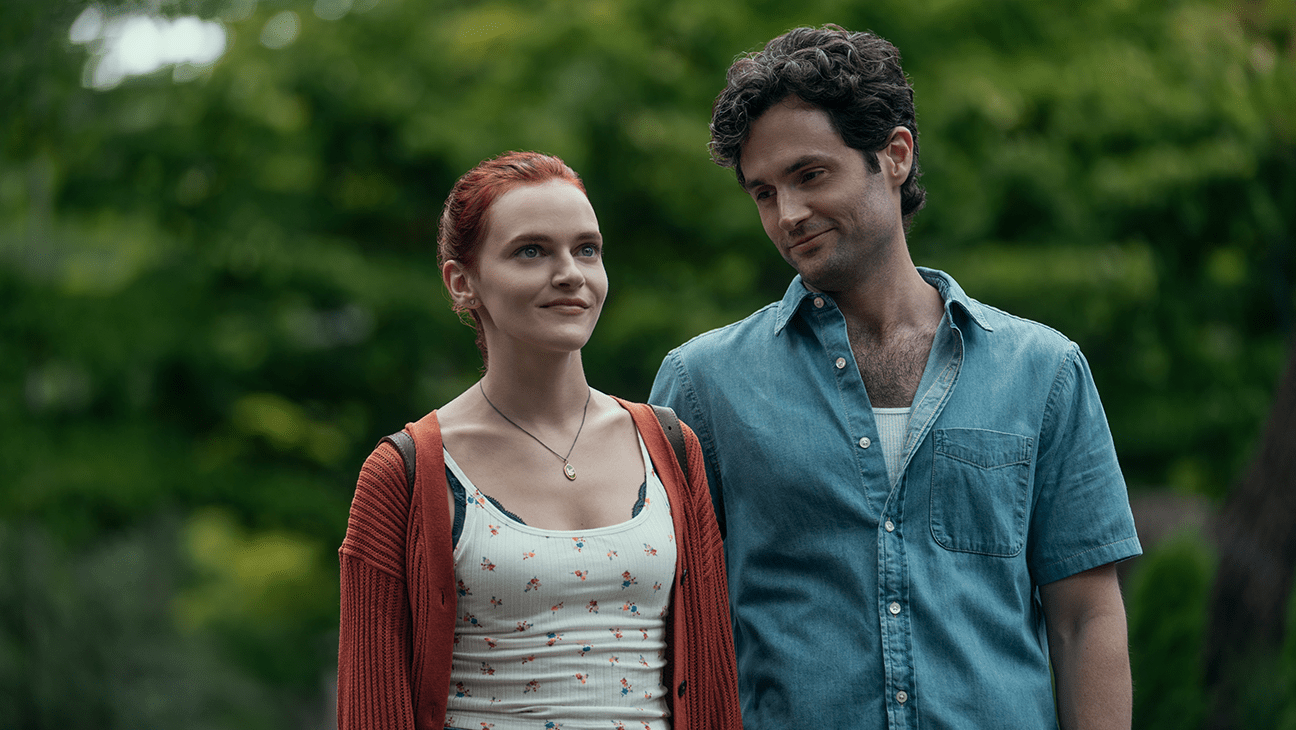

Michael Foley and Justin W. Lo, who took over the reins from co-creator Sera Gamble for the fifth and final installment of the series adapted from Caroline Kepnes’ novels, delivered a jaw-dropping conclusion to the series, which saw twists and turns throughout the season as Joe returned to New York City. That included Kate (Charlotte Ritchie) agreeing to let Joe kill her uncle to Joe finding his new obsession in Bronte/Louise (Madeline Brewer) — but the latter took an unexpected turn when it was revealed that Bronte was actually out to avenge Guinevere Beck’s (Elizabeth Lail) death from season one.

But few could have predicted the epic, brutal and lonely ending for Joe, which Foley tells The Hollywood Reporter was “very deliberate,” as they planned their stark pivot from “road trip romance” to “horror film” in order to deliver his ultimate comeuppance.

When Bronte pulled a gun to reveal herself to Joe, the once-charming serial killer fought back and nearly brutally killed her. But Bronte was able to call the police, who arrived just in time, and when she got her second chance to kill Joe, she instead karmically shoots Joe in his genitals. The police arrest him and an epilogue reveals that he went to trial and was convicted on multiple life sentences without parole. Bronte, now Louise, ends up being the Joe victim who is able to serve up justice in the end. But the final scene features an imprisoned Joe reading yet another piece of fanmail and positing a final question for You‘s audience: Was Joe the problem, or is society the problem?

Foley explains of delivering a dehumanizing ending for Joe, “We were trying to pull the civilization out of him. It was all about the animalistic nature of Joe, and that’s what I was speaking to with Penn in terms of, in the end, we just need to see the monster for what the monster is. That’s why the back half of the finale was a horror film.”

While there were many variations of Joe’s ultimate ending that were discussed in the writers room, Foley says that killing Joe would have been letting him off the hook. “We were definitely all not on the same page, and in the end, we just thought that death was too easy and that that wasn’t punishing enough,” he explains. “We liked the idea of a final image of Joe in a cage of sorts, but most of all, it was about taking away his power, taking away his ability to know the touch of a lover, etc.”

Below, Foley and Lo unpack season five, including Joe’s downfall, Kate’s lapse in judgment early in the season, Anna Camp taking on two characters, the decision to have Joe get shot in his manhood, who they wish they could have been brought back for the finale and their conversations with Badgley about making sure “Joe was at his most horrific this season.”

***

Was there any added pressure taking over for Sera Gamble for the final season?

MICHAEL FOLEY There was certainly added pressure because it’s a giant Netflix hit, and it’s been mainly the same writing crew since the beginning. I’ve been saying that it’s Sera who was captaining the ship, and there’s no one else like Sera Gamble. But she got us to the point where she was like, “That’s land right there. Keep rowing, keep sailing as you will.” So we really felt confident coming into this. All of the writers, we know how to write and produce the show, so [we’re] nothing but confident and excited.

JUSTIN W. LO Sarah’s voice was so clear and intentional in the way she and Greg [Berlanti, co-creator] created the show that we were able to keep doing what we’d always been doing. The mission was the same every season.

FOLEY Also Sera and Greg were both there, so we had discussions with them at the beginning of the season. We had discussions with them around the finale.

What was it like returning to New York City and going back where it all began for this final chapter? What conversation did you have with Penn?

FOLEY The dominant thing with Penn was that he wanted to make sure that Joe was at his most horrific this season, and especially as we approached the finale, he was on the same page with us in terms of our goal being to wake us all up to what we’ve been rooting for and co-signing. He was really intent on us not pulling any punches with just revealing what a monster Joe Goldberg is.

At the beginning of the season, Kate has a lapse in judgment and agrees to have Joe kill her uncle. But she quickly regrets the decision, confusing Joe because he thinks he’s found someone who understands even his darkest desires. Why did she make that decision?

LO We saw that as Kate’s moment of weakness. Kate has always been considered to have a killer instinct and able to make these tough moral choices, and not always in the most benevolent way. So she has this moment of weakness and for her, that’s her lowest point, but for Joe, it begins this trajectory where he is feeling empowered and emboldened in his dark side coming back out.

After that bomb drop mid-season that Bronte (Madeline Brewer) was actually out to avenge Beck’s (Elizabeth Lail) death, she still finds herself swept up by Joe for a bit. Why do you think that is?

FOLEY I think for the same reason that we all fell for Joe. That he’s charming. That he claims to do everything he does in the name of love. They were very much on the same page in terms of just seeing hypocrisy in the world.

Anna Camp had the challenge of portraying two characters this season with twins Maddie and Raegan Lockwood. What conversations did you have with her regarding her storylines and taking on dual roles?

LO I don’t think we had a lot of conversations before what she brought to the days that we were shooting. She showed up already knowing how to differentiate the characters. We didn’t have to say, “Maybe one should have a voice this way or maybe one should walk this way.” She’s a very accomplished actor and she came in with her choices and they really worked for the show.

I can only imagine the challenges that came with shooting the box scenes with Anna’s two characters, especially with the reflections from the glass. Can you talk about filming those sequences?

FOLEY With really accomplished directors. Any day in the cage is going to be the toughest day of any shoot, because, as you said, reflections. It’s just the hardest thing in the world. So the fact that we were covering a double made it really difficult and we covered ourselves with having incredibly capable directors. I have the most credit to give to Anna because for her to hold on to both those characters, and all the distinctions and the ticks and the body movements, it was really a master class she put on.

LO Also we hired not just a double, but an actor to play the other parts when she was acting opposite herself. We auditioned them and did a chemistry read with Anna. It was really important they had a sisterly chemistry and that each one could study the other as they were doing their take, so they would know exactly where to place the eye line, what motions they did on what line. So it was very technical, too.

When the viral video makes Joe the “most visible man in New York,” it appears as though that will be his downfall, but he still manages to turn that around. Was that decision intentional to play into the suspense of whether Joe is actually going to get caught?

FOLEY The thing we were most excited about was that his weapon and tool over four seasons, that being social media, is used against him. That excited us to no end. We also liked that we got to sort of hold the mirror up to the reality that people — maybe not as bad as Joe, well, some of them — do survive such awful transgressions.

LO One of the most fun parts about that episode was coming up with the comments on that YouTube video live stream. It was so fun! We had to come up with positive ones in support of him, ones that were obviously critical, but also ones that are just funny. We were actually trying to time them to what was happening and the picture right on screen, to tell the story in a realistic way. Not everyone would be on his side, not everyone would be against him. That was one of the most fun things we did this season.

How satisfying was it to bring episode nine to life, when the roles get reversed and Joe ends up in the box, facing several of his past victims who have survived?

LO That episode is called “The Trial of the Furies,” and the furies were the Greek goddesses of revenge. This was our nod to letting Joe’s victims who had survived him have their revenge on him and put him on trial. So when he’s in that box, they get to stand opposite him and say whatever they need to say to him and to see if he’s going to actually be changed by it or take any responsibility for it, which he does not.

Once Bronte got back on track and decided to take Joe down, why did she go about it alone and almost get herself killed in the process rather than ask for help?

FOLEY Because we knew that if she asked for help and the authorities closed in, she would never get the answers she was after. She really needed the truth about Beck. She needed to take Beck’s voice back by having Joe redact The Dark Face of Love. Once Joe had lawyered up and was in a jail cell, these are answers she wasn’t going to get.

So after five wild seasons, from your perspective as showrunners, why is Joe the way he is?

LO We’ve shown in several seasons Joe’s traumatic childhood. That’s part of it, but it’s not all of it. There is something in Joe that is broken, and the reason that we are drawn to Joe is because he masks that brokenness in this desire for love. He says that love is the reason he can do these terrible things that he does and it justifies it. But I think it’s a combination of something innate and also the trauma that he experienced as a child, the lack of love and the abandonment by his mother.

FOLEY There was sort of a mandate in the [writers] room early on that we were never going to diagnose Joe, because that would then lead to empathy and we didn’t want that. The closest we came, though, was in episode eight when Louise does diagnose him to a degree and basically helps him realize that, because of his childhood trauma, there was a protector that was created that was cut off from him. It was like the beginning of the split identity, and that protector became the killer, and then the lines blurred and killing became an inherent part of love for him.

Throughout the series, Joe appeared to always present himself in an orderly way to the world, despite his chaotic dark inner thoughts. But at the end of the finale, he’s seen chaotically running through the woods. What’s the deeper meaning behind that scene?

FOLEY He’s not only in the woods, but he’s without clothes because we were trying to pull the civilization out of him. It was all about the animalistic nature of Joe, and that’s what I was speaking to with Penn in terms of, in the end, we just need to see the monster for what the monster is. That’s why the back half of the finale was a horror film. That’s why he attacked and burst through doors the way he did, bloodied, bursting through doors, punches. We showed the violence, which we usually pulled back on — his violence in the fight in the bedroom with Bronte, with Louise, I should say, at that point. That was the reason, to really unmask the monster as much as we could.

I found the contrast between the first and the second half of the finale very intriguing.

FOLEY That was very deliberate that it was the first half that Joe thinks he’s riding off in the sunset with the woman who can love all of him — so let’s let him enjoy that, not knowing that Bronte has a secret agenda. And then, of course, when she unmasks midway, our road trip romance is over and we’re into a horror film.

Can you also talk about the message behind Bronte deciding to shoot Joe in his genital area?

LO That was obviously to take away Joe’s power, his manhood and what makes him a romantic icon, a sexual icon. It was important to us, and definitely important to Penn, to take as much as we could from Joe at the very end of the series.

It was such a nice surprise to see Kate survive the fire at Mooney’s. Was that always the plan, to let her survive?

FOLEY It’s funny because, we killed Beck, right? She was innocence incarnate. This young woman trying to figure out who she was and Joe took advantage of her. Joe kills her. Sometimes when it came to killing, when we were in the writers room, we were like: That’s just bleak and not additive, that’s just gonna make the audience feel worse. We know what Joe is, and we don’t see how that’s in any way additive creatively. So why not let this woman who absolved herself, who was willing to go down and die in that basement like she was and who was after redemption, why not give it to her?

It’s also nice to see that Henry (Frankie DeMaio) still has someone.

LO We did think a lot about Henry and where he would end up. It was good and right that he would end up back with Kate.

Can you expand on the final scene with Joe in his prison cell and why he appears to be casting judgment on these fans sending him letters, expressing that they believe him, when he just wanted someone to understand him this whole time?

FOLEY I don’t think he’s casting judgment on these women who are writing him letters, right? They’re the few who accept him. He’s casting judgment on society. He’s casting judgment on everybody else who just paints him as a bad guy. … That was all but posted in the writers room, which was: Joe will never see that the problem is him. It’ll always be someone else.

Is there anything you had to cut from season five for timing or consistency that you wish could have made the final edit?

FOLEY It’s so funny the things that get cut, they go out of my mind so quickly, right? We would have loved to have gotten Ellie (Jenna Ortega) back, but that was too complicated.

Was there any discussion about potentially bringing back fan-favorite Love Quinn (Victoria Pedretti)?

There wasn’t just because… we understand she’s a fan favorite. We love the character, we love Victoria Pedretti. Like, great if somebody came up with the right idea. But her character is dead, and we had already used the ghost of her to be in Joe’s head last season. So it felt like we had been to that well already and that her run was done. As writers, it just felt correct that she wasn’t part of the season.

The end was definitely satisfying, seeing the way Joe finally got caught, but did you ever ponder alternate endings, such as one where Joe gets away with everything?

FOLEY For sure. We knew what we were doing in terms of Joe getting his comeuppance, Joe facing the loved ones of victims, Joe shirking accountability when the time came, all the general ideas we were all in agreement on. But in terms of capture, death, captured by the authorities, captured by a loved one, of a victim… there were some really crazy ideas (laughs). We were definitely all not on the same page, and in the end, we just thought that death was too easy and that that wasn’t punishing enough. We liked the idea of a final image of Joe in a cage of sorts, but most of all, it was about taking away his power, taking away his ability to know the touch of a lover, etc.

LO To add to the endings that Mike was talking about, we came up with one where it’s an ambiguous ending, Sopranos-style where Bronte is pointing a gun at him and you don’t know if she’s going to pull the trigger or not, and then it’s a cut to black. We came up with the one that Mike was alluding to, with a more Gothic ending where someone puts him in a cage buried deep underground. So we went through many, many iterations, but I think we’re really happy with where it ended up.

FOLEY Even though all season and for years we were talking about Joe’s end — like water cooler talk, it’s very much what we’re talking about in the room — as we were headed to the last few episodes and we had to work out the specifics, a writer in our room, Neil Reynolds, said, “Can we just try something different instead of doing the writers room as we normally do it? Can we take a day where everybody has their five minutes or however much time they need to discuss their POV on what Joe’s end should be and why, and let’s all just hear it and then nobody can interrupt, nobody can note,” like very much not writers room, right? And you all go away, process it and then let’s all come back in and let’s have a discussion.”

It was extremely emotional, because most of us had been with the show since 2017. When it comes to messaging and what Joe stands for and what we’ve been doing with this show, it’s very personal to all of us. There were tears. It was a very beautiful exercise that we did to help us all get on the same page about what the ending would be.

***

You season five, along with all seasons of the series, is currently streaming on Netflix.

Source: Hollywoodreporter

HiCelebNews online magazine publishes interesting content every day in the TV section of the entertainment category. Follow us to read the latest news.

Related Posts

- Ciara Reveals When She Wants to Start Trying for Baby No. 5 with Husband Russell Wilson (Exclusive)

- Hamdan Ballal Pens Candid Op-Ed About West Bank Assault: “Our Movie Won an Oscar, But Our Lives Are No Better Than Before”

- Tina Fey Embraced “the Sandler Model” for New Show ‘The Four Seasons’: “Actors in Nice Locations, Wearing Flat Shoes”

- Morgan Wallen’s Ex KT Smith Reveals She’s Back Together with Husband Luke Scornavacco After Announcing Split

- The Vibes Are (Purposely) Off in Netflix’s ‘Sirens’ Trailer